Jenna Cassinat and Dr. Alexander Jensen, School of Family Life

Introduction

As individuals leave behind adolescence for adulthood, they suddenly encounter many decisions to make about their life and identity (Arnett, 2006; Schwartz, Côté & Arnett, 2005). Marriage is just one of the areas where they must determine what their beliefs and ideologies are. With such significant changes to marriage as an institution in the past several decades (Snyder, 2016; Obergefell et al. v. Hodges, 2015)—including the rise of cohabitation (Schoen, & Standish, 2001)—emerging adults must now decide if marriage is something they want for themselves (Bumpass, & Lu, 2000; Guzzo, 2014; Bumpass, Sweet, & Cherlin, 1991). There are those who see marriage as old-fashioned and unimportant while others still look to marriage not only as a life goal, but also as a central part of life (Guzzo, 2014; D’Vera Cohn, Wang, & Livingston, 2011; Willoughby, Carroll, Vitas, & Hill, 2012; Carroll, et. al. 2007). Thus, emerging adults have differing views about both marital centrality and expectation of marriage.

Why do emerging adults have such differing opinions on the importance of marriage? Previous research has looked at different sources of these beliefs and behaviors, including parents, friends and media (Thornton, 1991; Axinn, & Thornton, 1992; Larson, Benson, Wilson, & Medora, 1998; Lefkowitz, Boone, & Shearer, 2004; Hill, 2005). While each of these is, of course important (Wilks, 1986), virtually no research has explored the influence that siblings may have on attitudes about marriage. The aims of this study were to examine siblings’ influence on marital centrality and expectation of marriage in emerging adulthood. Specifically, I examined the processes of modeling and differentiation, within the context of birth order.

Method and Results

Data was drawn from the Sibling Influence on Becoming Adults Study (SIBS) which examined the role of siblings in emerging adult participants’ attitudes surrounding adulthood. The entire study included 1,750 individuals across the United States of America. The original study included individuals of all types of relationship status, however, for this study I used only unmarried participants, giving a final sample size of 1,276 (see Table 1). Participants were between the ages of 18 and 29 (M = 25.05; SD = 2.60) with at least one living sibling. Each sibling reported on the demographic data of their closest aged sibling; of the siblings 18.57% were married. The participants were almost evenly split (male = 670; female = 606). The average age difference between siblings was 4.06 (SD = 3.36) years, with most participants reporting on an older sibling (55%). Surveys lasted about 20 minutes. Participants were paid $2.25 for taking the survey.

Each participant reported on their level of marital centrality and their expectation of marriage; they then reported on their perceived sibling’s marital centrality and expectation of marriage. To analyze marital centrality Ordinary Least Squares Hierarchical Regression was run; to analyze expectation of marriage a Binary Logistic Regression was run. Each analysis examined the role of siblings as emerging adults form their marital identity using modeling and differentiation as moderators.

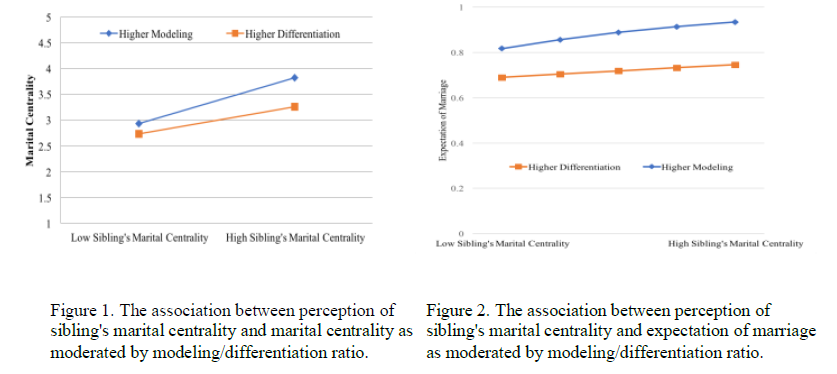

Analysis of marital centrality showed a significant interaction between the ratio and participant’s perception of marital centrality in siblings (see Figure 1; b = .32, SE = .10, p < .01, β = .09). Testing of the simple slopes revealed that the association was significant when the participant had high levels of modeling (b = .53, SE = .06, p < .0001, β = .44) and when the participant had high levels of differentiation (b = .31, SE = .06, p < .0001, β = .26).

Analysis of expectation of marriage showed a significant interaction between the modeling and differentiation ratio and sibling’s perception of marital centrality was significantly positive (see Figure 2; b = .79, SE = .27, p < .01, OR = 2.19). Testing of the simple slopes revealed that the association was only significant when the participant had high levels of modeling (b = .69, SE = .16, p = .0001, OR = 1.98).

Based on these analysis, my hypothesis was generally supported; siblings may play an important role in emerging adults’ attitudes about marriage. I found that for those who model a sibling that they believe finds marriage important, they are more likely to view marriage as important and are more likely to expect marriage for themselves. As hypothesized, the perception of a sibling’s attitudes toward marriage were heightened when they modeled that sibling more than they differentiated. This may mean that siblings play an important role as emerging adults form their marital identity. It seems that when an emerging adult wants to be like their sibling, they model their beliefs of how they believe their sibling feels. Siblings, seem to play a role in helping emerging adults decide if they want (or expect) to get married and they play a role as individuals determine how important marriage will be in their own life.

This study contributes to literature about emerging adult’s identity formation and about sibling processes during emerging adulthood. This study revealed that siblings have an important influence on marital centrality and expectation of marriage. Additionally, this study helped to establish modeling as a salient influence for emerging adults—more so than differentiation. Furthermore, by using a unique approach, this study was not only able to clarify the different influence that modeling and differentiation has in emerging adulthood but it was also able to emphasize how important modeling is. Finally, this study helped us to understand the changing nature of sibling relationships as they may become more egalitarian in emerging adulthood. Future studies must consider these findings as they continue to explore emerging adulthood and sibling relationships.