Brent Foster and Dr. Steven Luke, Neuroscience Department

Introduction

Humans comprehend language at varying levels of complexity. Syntax, in particular, deals with the arrangement of words and phrases into meaningful sentences. For instance, in English we expect most sentences to follow some variation of the order “Subject–Verb–Object” such as “The boy (Subject) ate (Verb) cake (Object).” On the surface, such grammatical rules seem simple. However, our understanding of how the brain implements these rules to understand sentences is incomplete.

In fact, the viewpoint of a specific language center of the brain may be oversimplified. When processing syntax, the brain appears to activate multiple areas not specific to syntactic tasks alone (Grodzinsky and Friederici, 2007). Particularly, the IFG is expected to activate to reorganize syntactic patterns when exposed to conflicting or “high-surprisal” sentences (Henderson et al. 2016). The brain may therefore be viewed as a type of “prediction machine” (Clark, 2013) that affects cognitive functions (Lupyan and Clark, 2015). Language processing, then, may be considered a process of predictions where linguistic probabilities are computed in order to facilitate language comprehension. Predictions can make language processing more efficient during both reading and listening (DeLong et al., 2014). However, the means by which humans utilize the predictive power of the brain during language processing is yet to be fully elucidated. The primary purpose of this study was to determine the network for neural syntactic processing via fixation-related fMRI and syntactic predictability.

Methodology

Reading passages were selected and standardized from sources such as newspaper articles and classic children’s literature. Every word was given a predictability value according to context. Data was collected from 43 participants (18 females), ages ranging from 18 to 25. Eye movements were recorded via an SR Research Eyelink 1000+ eye-tracker. Functional and structural brain scans were recorded with a Siemens Trio 3T MRI machine housed in the BYU MRI research facility on campus. MRI scans were analyzed with AFNI and ANTs.

Results

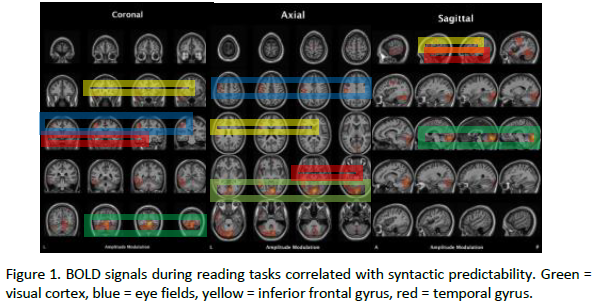

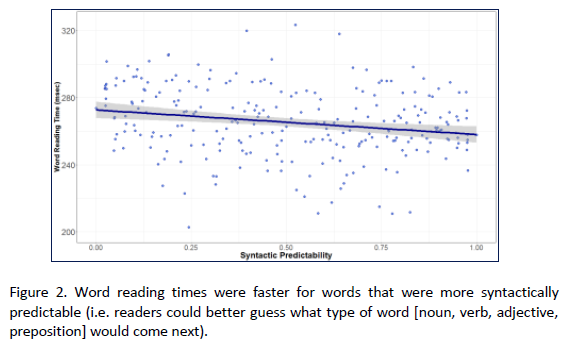

Blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals correlated with syntactic predictability were found in four brain regions: 1) visual cortex, involved in processing visual information, 2) frontal and supplementary eye fields, which control where we look, 3) left Inferior frontal gyrus (which contains Broca’s Area), a region commonly implicated in syntactic processing, and 4) left superior temporal gyrus, a region involved in language processing in general and syntax specifically. See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of brain activation patterns. Figure 2 describes the behavioral trends.

Discussion/Conclusion

Our preliminary findings were presented at the Mary Lou Fulton Undergraduate Research Conference, and our team is currently preparing a manuscript for publication. These results corroborate previous findings from research studying syntactic processing (Henderson et al., 2016). Our next steps will involve exploring the structural and functional connectivity of these regions with each other and with other regions of the eye movement network, to better understand how syntactic predictability influences how we read. This research is important in helping us understand how syntax rules are implemented in the human brain. Such an understanding is beneficial for both health practitioners and researchers in language acquisition and learning. Once the syntactic network is understood, doctors and speech pathologists can better identify problem areas in the brains of patients with various language deficits ranging from dyslexia to language-specific aphasias (caused by strokes, traumatic brain injuries, or other neural tissue damage). This research could also clarify how second-language learners implement syntax rules that differ from their native language. This could provide valuable information that may enable researchers to improve methods of second-language learning.

References

- Clark, A., 2013. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behav. Brain Sci. 36, 181–204.

- DeLong K. A., Troyer M. and Kutas M. (2014) Pre-Processing in Sentence Comprehension: Sensitivity to Likely Upcoming Meaning and Structure, Language and Linguistics Compass, 8, pages 631–645.

- Grodzinsky, Y., & Friederici, A. D. (2006). Neuroimaging of syntax and syntactic processing. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 16(2), 240–246.

- Henderson, J. M., Choi, W., Lowder, M. W., & Ferreira, F. (2016). Language structure in the brain:

A fixation-related fMRI study of syntactic surprisal in reading. NeuroImage, 132, 293– 300. - Lupyan, G., Clark, A., 2015. Words and the world: predictive coding and the language-perception-cognition interface. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 24, 279–284.