Stephen Hunasker, Ana Kuphunzitsa, and Dr. Donald Baum, Education Leadership & Foundations Department

How much would it cost to send a single student to secondary school for a year? In Malawi it is a mere $300, that comes up to less than a $1 a day to go, yet it is common for these families to be living on less than a dollar a day1. This research that was conducted on the ground in Malawi looks at how effective and beneficial a scholarship that completely paid for the schooling of certain children would be. The study utilizes a causal-comparative research design to compare the educational experiences and outcomes of two student groups – those who did and those who did not receive a needs-based scholarship to attend secondary or tertiary school. We administered surveys to 89 scholarship recipients and 57 non-recipients in the Dowa, Kasungu and Lilongwe Districts of Malawi.

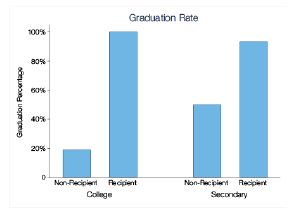

Our findings show that, overall, scholarship recipients were able to access boarding schools, attend school, and avoid withdrawal at higher rates than their non-recipient peers. In part, this was due to a reduction in the out-of-pocket costs associated with attending school. On average, scholarship recipients attain an additional year of schooling. Some of the largest findings show that at both secondary and college levels, between 94%-100% of students are graduating compared to 50%-19% for non-recipients (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: The graduation rates of each group. The secondary recipients were at 94% because one girl failed final exams and was in the process of retaking them.

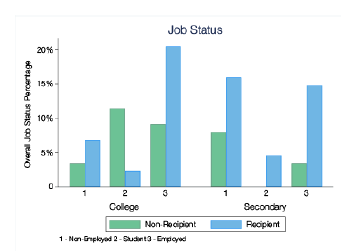

Additionally, we find that former recipients are more likely to be employed and currently have higher income levels than former non-recipients of the scholarship (See Figure 2). However, the scholarship did not produce significant effects across all outcome measures. We find no differences between recipients and non-recipients on measures of job quality and the self-reported measure of relative wealth. We believe this is due to the job market of the country as a whole. Numerous former students conveyed that there is not market for their profession, even common ones like accounting. Therefore, even though recipients of the scholarship were more likely to be employed the quality of those jobs were not significantly better than the non-recipients.

Figure 2: The overall percent of former students that were unemployed, students, and employed.

This study provides new insight for policy makers on constraints to school access and completion, as well as possible solutions for supporting student persistence through school. Our findings provide evidence that scholarships for secondary and tertiary students help break down barriers that constrain students from being able to enroll, progress, and graduate from school. However, the results also highlight the necessity of education for students beyond the secondary level. Specifically, we find that those secondary school graduates who fail to receive higher education and remain in agriculture-based employment are usually no better off than those who failed to complete their secondary education. Therefore, secondary-level scholarships might not directly translate to higher incomes and better livelihoods for all rural students; but, they do allow students to become stronger applicants for further education and social impact. Ultimately, financial support for students may offer even greater value by combining funding for secondary and tertiary schooling to provide students with the skills necessary to enter the formal labor market.