Jacob R. Hickman

Overview

Hmong are a highland ethnic minority group that span the Southeast Asian Massif, including

China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. Many Hmong see China as an ancestral homeland, the

origin of a two-centuries-long diaspora spurred on by conflict. The research funded by this MEG

grant was designed to address questions of how Hmong have adapted to distinct social and

political circumstances as they have migrated to new locations, and changes in their subsistence

methods, cultural practice, and attitudes toward state governance. This project holds special

academic value for its reach to China, a perceived origin of Hmong culture, and comparison to

Vietnam, a region of early migration for Hmong escaping persecution. In order to cultivate a

mentored environment where students could receive close training and help design and carry out

substantive research projects, the PI organized an ethnographic field school in two Hmong

communities for 6 weeks each during the summer of 2015. The primary field sites for this

research were chains of Hmong villages approximately 60 miles apart, one in Northern Vietnam,

the other in Southern China. The PI and students engaged in this research were seeking to

conduct ethnographies of everyday practice that would reveal some of the dual psychological

and cultural dimensions to how Hmong are positioning themselves in their contemporary

political context, including the new and innovative ways that they are wielding cultural resources

to this end. These strategies included new ritual innovations, reimagining Hmong history and

asserting new forms of that history, changes in ethical thinking that adapt to new economic

circumstances, and large-scale shifts in identity politics in which Hmong are recasting Hmong

identity in terms that make more sense of the current sociopolitical climate. To this end, students

tailored their senior thesis projects under close mentorship with the PI to develop additional

dimensions of this larger project that explore further dimensions of how Hmong have adapted to

new sociopolitical circumstances. Thesis projects built on this to understand how this history

plays into a series of related phenomena, as described below.

List of Students and Products

PI and Additional Mentors

Dr. Jacob Hickman, Principal Investigator (BYU Faculty)

Mai See Thao, ABD, University of Minnesota (Additional Mentor)

Dr. Eric Hyer (BYU Faculty, Additional Mentor)

Students in the Field School

Mary Cook (BYU undergraduate)

Ricky Gettys (BYU undergraduate)

Jamie Gettys (BYU undergraduate)

Seth Meyers (BYU undergraduate)

Danny Cardoza (BYU undergraduate)

Brittany Paxton (BYU undergraduate)

Austin Gillett (BYU undergraduate)

Jordan Baker (BYU undergraduate)

Scott Burdick (BYU undergraduate)

Matt Doane (BYU undergraduate)

Davey Cox (BYU undergraduate)

John Trey Kidwell (University of Arkansas undergraduate)

Vinicius Owen (Purdue University undergraduate)

Cody Abernathy (Eastern Illinois University undergraduate)

Chinou Vang (University of Wisconsin-Madison- graduate student)

Maie Khalil (University of Florida undergraduate)

You Lee (University of Wisconsin- Stevens Point undergraduate)

Chee Lor (University of Wisconsin-Madison-graduate student)

Research Assistant

Joseph Vang (BYU undergraduate)

Paul Xiong (BYU Undergraduate)

Products—International Conference Presentations

Paxton, Brittany. (2016). “Threads to Break; Threads to Bind: Embodiment, Ritual Among the

Hmong.” American Anthropological Association Annual Conference. Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Daniel Cardoza. (2015). “Compounding Moral Personhood: How Conversion Changes

Everything, or Not.” American Anthropological Association Annual Meetings. Denver,

Colorado.

Mary Cook. (2015). “Learning English in the Hills of Vietnam: Informal Education Models and

Evolving Gender Dynamics in Highland Hmong Society.” American Anthropological

Association Annual Meetings. Denver, Colorado.

Eric Austin Gillett. (2015). “Finding the Deontological within the Ontological.” American

Anthropological Association Annual Meetings. Denver, Colorado.

Seth Meyers. (2015). “The Political Economics of Captured Brides: Towards a New Perspective

on the Socioeconomic Implications of Kev Zij Pojniam in Two Hmong Villages.” American

Anthropological Association Annual Meetings. Denver, Colorado.

Brittany Ann Paxton. (2015). “Person Centered Ethnography in Gender and Tourism Studies.”

American Anthropological Association Annual Meetings. Denver, Colorado.

Corbett, Cheryl; Jamie Gettys. (2015). Women and Birth: A comparison of Experiences Across

Cultures. Women of the Mountains International Conference. Provo, UT.

Gettys, Jamie; Corbett, Cheryl. (2015). Challenges in Conducting International Research:

Observations in Rural Villages of India, Vietnam and China. BYU College of Nursing Scholarly

Works Conference. Provo, UT.

Ricky Gettys. (2015). “Modeling Minorityhood: ‘Official’ Policies and ‘Unofficial’ Politics.”

Hmong Studies Consortium Biennial Conference, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Austin Gillett and Jacob R. Hickman. (2015). “Tradition, Agency and Emotion in Hmong Moral

Discourse.” Society for the Anthropology of Religion Biennial Meeting. San Diego, CA.

Brittany Paxton. (2015). “Hmong Culture and Gender as Objects of the Tourist Gaze.” Hmong

Studies Consortium Biennial Conference, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Jolysa Sedgwick. (2015). “Pandora’s Hope for Hmong Identity in a Relocation Community in

Thailand.” Hmong Studies Consortium Biennial Conference, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Gillett, Austin. (2015). Moral Anthropology Among the Hmong. Society for the Anthropology of

Religion biennial meetings, April.

Owen, Vinicius. (2015). “Ethnic Tourism in the Hills of Northern Thailand”. Society for Applied

Anthropology, March.

Products—Works Submitted for Publication or in Preparation for Publication

Corbett, Cheryl, Jamie Gettys, Lynn Callister, and Jacob R. Hickman. (Under Review). Giving

Birth: The Voices of Hmong Women Living in Northern Vietnam. The Journal of

Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing.

Hickman, Jacob R., Danny Cardoza and Lindsey B. Fields. (In Preparation). The Ancestors

Don’t Live in Hell: On Belief and Ontology as Distinct Modes of Understanding. (To be

submitted to American Ethnologist).

Cook, Mary, and Jacob R. Hickman. (In Preparation) Psychocultural Landscapes of Hmong

Polygyny: Individualism and Collectivism Reconsidered. (To be submitted to Ethos).

Gettys, Richard; Hickman, Jacob. (In Preparation). Vestiges of the Mandate of Heaven: Hmong

Morality and Resistance in Vietnam. (To be submitted to the Journal of Peasant Studies).

Cook, Mary; Hickman, Jacob. (In Preparation) Transforming Marginality: Redefining Hmong

Ethnic and Female Identity through Development in Sapa, Vietnam. (To be submitted to

the Journal for Vietnamese Studies special issue).

Meyers, Seth; Hickman, Jacob. (In Preparation) “Nobody Gave Me Power:” the Phenomenology

of the Experience of Captured Hmong Brides in Northern Vietnam. (To be submitted to

the Journal for Vietnamese Studies).

Paxton, Brittany; Hickman, Jacob. (In Preparation) Threads to bind Threads to break: Gender,

Paj Ntaub, and Agency. (To be submitted to the Journal for Vietnamese Studies).

Evaluation of Academic Objectives

The 2015 China/Vietnam Ethnographic Field School was a success on several fronts. As outlined

above, this program that was funded by this MEG grant led directly to 14 presentations at

international conferences at the largest professional academic associations in the country. These

included presentations at the 2015 and 2016 annual meetings of the American Anthropological

Association, and the Hmong Studies Consortium Biennial Meeting at the University of

Wisconsin-Madison in 2015. Students presented the findings from their fieldwork and received

quality feedback to help them develop that work for publication. These presentations made an

impression on faculty from several top research universities, who were impressed with the

quality of work that came from undergraduates in the program.

Further, this work that students presented is currently being further developed by the students

and the PI for possible publication in either a special issue of the Journal of Vietnamese Studies

(published by the University of California Press) or an edited volume with an academic press. In

the case of the journal articles outlined above, the students who conducted the bulk of interviews

will be listed as the first author, and the PI as the second author. Many of the students developed

the first drafts of these manuscripts as their senior thesis, and afterwards the PI has been working

with each one to get the project up to par to be submitted to other high-tier journals in relevant

sub-disciplines to the work, i.e., Ethos, The Journal of Peasant Studies, and the Hmong Studies

Journal.

In addition to these tangible products—international conference presentations and manuscripts

being developed for publication, this program also resulted in a broad dataset of information that

can be used in future research that builds on these research questions concerning how Hmong

adapt to new social and political contexts. The PI debuted a database of all of the interviews,

fieldnotes, recordings of rituals, photos, and other ethnographic materials from past Field schools

in a Filemaker Server platform that allowed new materials to be catalogued, summarized,

searched, and analyzed in future work. This database will grow in future projects as the PI carries

out future research in other locations of the Hmong diaspora (such as his planned field school in

2016 among Hmong villages in France). Just from students data collection in the 2016 field

school, the data amassed and catalogued in this database include roughly 1,800 pages of field

notes, 500 digital audio recordings of interviews or naturally-occurring discourse or rituals,

roughly 50 digital video files, and a large database of digital photographs and scanned

documents, all collected during the three months of fieldwork on these projects. Total, the

database features almost 3000 pages of field notes, 700 audio recordings, and over 300 video

files. This database includes descriptions of projects and contextual summaries for these items,

keywords, such that future researchers or the PI could go back to this database and find relevant

material to analyze in future projects. Students in the program not only learned principles of

social science research design, but also crucial skills of data management and analysis, as they

helped amass this systematic database of primary ethnographic data. Critically, this database is

thoroughly indexed with metadata that will help researchers find and analyze relevant data in

future projects.

The students also worked with the PI in developing a survey grounded in the local norms to

expand their data collection methodology and get data that is generalizable to the larger

population. The students drafted questions for the survey based on types of data relevant to their

project while the PI helped hone the questions to make sense in the cultural setting. Students

were then responsible for collecting data on iPads, and received training on survey interview

techniques and survey data analysis. Students were trained by the PI to code and analyze all

ethnographic and demographic data with computer assisted qualitative data analysis software

(CAQDAS) while in the field, and get a head start on data analysis while still in the field. Early

data analysis allowed the projects to be dynamic, adjusting projects to emerging trends while still

in the field, and allowing students to work more efficiently toward publication of these projects.

Evaluation of the Mentoring Environment

The PI and the students in the program found the field school and all of the mentored research

conducted after the field school to be incredibly productive for all involved. For the PI, this was

an opportunity to get motivated and ambitious students involved in his research and to expand

his ethnographic reach in the community as students conducted interviews and observations to

supplement his own during the summer on topics closely related to his own research. In many

instances, student interests and ambitions even pushed the research questions productively in

new (but still related) directions, such as Jamie’s interest in birthing practices, or Ricky, Scott,

and Matt’s interest in the intersections of political science and anthropology. In all of these cases,

we developed a productive synergy that led to projects that expand the PI’s horizon of topics that

fall under his umbrella research questions, and also helped students channel their interests into

particular phenomena and building off of the PI’s former work to carry out productive projects

that also addressed their own research interests. Overall, three main groups of research were

addressed; Medical Anthropology, Economic/Political Anthropology, and Moral Anthropology.

In some cases, students carried out interviews and observations based on the PIs current or past

projects. For example, Danny and Davey conducted in-depth interviews on ritual practices with

several elders in the community that provide crucial insights into the baseline of cultural models

that inform contemporary religious practice and ontological frameworks that underpin daily

ritual practice. Some students even replicated vignettes used by the PI in past projects to compare

responses in Vietnam and China to other places in the Hmong diaspora.

From the student side, participants in this program found their training to be an invaluable

research experience. Students were not mere research assistants to the PI, but rather played a

driving intellectual role in developing research questions and designing methods to adequately

address those questions. While the PI provided close mentoring throughout the process, the

projects were subject to the directions that the students wanted to take them. The PI trained

students to understand and employ the logic of social science research design, and consistently

worked with students to hone methods that adequately address the research questions they were

pursuing. As such, both the student and the PI shared intellectual input into the nature of the

project and the ultimate products. In sum, students learned to perform a research project from the

point of conceptualization to design and through to analysis, utilizing a wide spread of methods,

rather than simply carrying out research tasks designated by the PI. This synergy proved

productive for all involved. In addition to the PI, who worked extensively with students prior to,

during, and after the field school, several faculty, some from other institutions were also brought

in to help mentor the group of field school students. Mai See Thao (ABD, University of

Minnesota) conducted research in the field school and mentored students in the field. We also

organized two research conferences two-thirds of the way into the summer of fieldwork where

students had to present their initial findings. The PI (Dr. Jacob Hickman), Mai see Thao

(University of Minnesota-Twin Cities), Dr. Eric Hyer (Brigham Young University- Provo), and

other faculty, ethnic leaders, ritual experts, and graduate students at Yunnan Nationalities

University attended these conferences along with the field school students, and gave students

critical feedback on their projects. This allowed an additional several weeks of fieldwork after

the conference for students to fill the empirical gaps in their projects. Students in the program all

agreed that this collective mentoring in the field and the conference itself forced them to improve

their projects significantly while still in the field with the ability to still engage in additional data collection.

Findings of the Field School

The findings of the research conducted on this field school all fall under the general research

question of ‘what are some root factors of how Hmong adapt culturally and psychologically to

new social circumstances’, but they are also focused on the outcomes of distinct thesis projects

conducted under this umbrella question. While the core findings of the PI’s research conducted

on this field school are being written up in a series of journal articles and possibly an eventual

book manuscript, what is outlined here emphasizes the findings of these mentored student

projects at present.

Austin Gillett’s research focuses on the ethical reasoning of Hmong handicraft merchants.

Drawing from classical philosophy debates between utilitarianism, deontological ethics, and

virtue ethics is living itself out in the current debate in anthropology in what many have been

calling the ‘ethical turn’ in anthropology. Michael Lambek’s edited volume Ordinary Ethics

argues that a look at ethics in the everyday gives us a “more accurate description of the way that

we live.” Lambek and others use tools from Aristotle’s virtue ethics to argue that ethics are

inherent to speech and action. He lays out a framework for thinking through the ethnography of

moral experience in Hmong communities, and argues that Hmong experience their moral worlds

as having a strong deontological component to them. By focusing on instances of language of

Hmong handicraft sellers—specifically the notion of “good-heartedness”— virtue ethics

overlooks the ethical work being done when our interlocutors look towards Hmong standards of

morality as they make moral decisions. While value still lies in the virtue ethics approaches that

provide good conceptual tools to understand ethical practice, these virtue ethics stances do not

fully account for the moral discourse of Hmong merchants or the ways that they engage in moral

judgment.

Danny Cardoza writes on his research on Hmong conversion. Theories of cultural change

frequently focus in on the discontinuation of local ways of finding truth, and how people turn

and demonize old ways. This is especially true of the literature on religious conversion from

local spiritual traditions to Christianity. These theories rely on a complete separation from the

indigenous ontology and the only role the pre-conversion ontology plays is to reinforce the

reality assumed through conversion. This allows for some level of shallow syncretism, but

consistently undercuts the meaning lent by the traditional ontology. He explores the ways in

which converts to Christianity experience the indigenous ontology as carrying more meaning

than a simple reinforcement of the new ontology, while not practicing the pre-conversion

religion in some sort of secretive fashion. He does so by exploring the implications of the

relationship of a Hmong Christian convert of twenty years with his two shaman pupils, as well as

interviews with interlocutors from his and surrounding villages near Sapa, Vietnam. From these

data we conclude that while there are instances that support the current popular theory of cultural

change, the compounding of the traditional ontology with that of the reality assumed through

conversion produces other nuanced instances that are neither simple reifications of the new

ontology nor are they secretive, but are representative of the reshaping of certain cultural

values that give precedence to neither ontology. Rather, he proposes a rethinking of syncretism

that allows for certain values to carry substantive weight in the newly combined ontology, while

not downplaying the importance of the values inherent to the postconversion ontology.

Seth Meyers work focuses on the experience of captured Hmong Brides in Vietnam. The

tradition of marriage by capture among Hmong of the Greater Mekong Sub-region has existed

for many generations. Among much of the documentation of Hmong communities over the last

century little has given specific focus to this topic. Much of the literature concerning traditional

forms of bride capture dwells mostly on the technicalities of the practice but little to no serious

efforts have been made to reveal the experience of individuals who participate in this activity. He

seeks to use ethnographic evidence through personal narratives of several women who were

married through capture to attempt an understanding of how women experience this practice.

Globalization has caused many cultural changes in Hmong communities around Sapa, Vietnam

and Wenshan, China. Women who are married by capture have to come to terms with an abrupt

redirection of their life course. Often goals of education and career must be put aside as family

and child-rearing take precedence. Understanding how women experience this type of marriage

can give crucial insight into the way in which certain members of Hmong society identify and fill

their roles in their respective communities. He finds that understanding how these women see

themselves as individuals as well as parts of their family and community helps shed light on the

many facets of the Hmong society makeup.

Ricky Gettys examines resistance to government policy implementation. In portrayals of

Hmong-American social activity, Hmong are characterized in some form as resistors of

hegemonic power. Undertones of Hmong resistance to incorporation into a state have

subsequently filled Western academia surrounding Hmong political activity throughout the

world, especially for scholars visiting Vietnam. He critiques this characterization of Hmong

action, because he feels it extrapolates ideas of Hmong social action stemming from involvement

in the Secret war and may be harmful as government leaders define Hmong as resistors of policy,

rather than taking into account Hmong agency, and the things that Hmong are advocating for. He

examines Hmong responses to questions about their political involvement during a governmentlead

relocation of a market from a central tourist area to the outskirts of the village. He then

analyzes the current resistance frameworks in respect to discourse of Hmong merchants, and

proposes that rather than resisting control of the state, these merchants are making a bid to be

better incorporated into the state decision making process.

Jordan Baker also investigated merchant resistance, but explores potential new avenues of

resistance. Some scholars argue that the Hmong and other ethnic minorities in South East Asia

are engaging in small and almost insignificant acts that passively resist modernity and the State.

With a rapidly modernizing and urbanizing landscape encroaching on their lands, Hmong in Sa

Pa are doing what they can to preserve their livelihoods and culture while still remaining

adaptable. Turner and Michaud argue that highland minorities in Lào Cai Province, particularly

the Hmong, are “playing their identities, traditions, and situation of political subordination and

geographical fragmentation to their advantage” (159). While these scholars have touched on

several ways that Hmong are achieving this particular kind of resistance—such as failing to

register as tour guides or refusing to plant government-issued seeds, she explores a new form of

resistance—place-making. In her research, she aims to add to Turner and Michaud’s claim by

particularizing the ways that Hmong in Sa Pa are place-making as a form of everyday politics

and resistance. She explores various ways in which Hmong street sellers are reimagining spaces

within Sa Pa to include themselves and preserve their culture. By inserting themselves into such

a hostile environment, she argues that the Hmong are engaging in a particular kind of placemaking

that has so far been ignored in Western-centric planning theory. Rather than a cocreation

of livable spaces by government bodies and local citizens, to her, place-making in Sa Pa

seems an act of cultural and economic survival and resistance.

Mary Cook’s findings provide a unique insight into identity transformation and education. Ethnic

relations in any given nation have traditionally been understood in overly simplistic terms of

minority resistance toward the majority ethnic group. In this fashion, Hanh (2008) follows the

identity transformation of Hmong girls in Sapa and ultimately argues that these young girls have

‘contested marginality’ by acculturating to the cosmopolitan scene. This acculturation is

facilitated through the development of symbiotic relationships with foreigners and the adoption

of modern practices which allow them to defy stereotypes imposed upon them by the Kinh

majority. In contrast to this model of resistance, Mary has found that Hmong women in the Sapa

tourist industry generate and integrate methods of development as ways to further transform their

ethnic and female identities in relation to the Kinh majority, and that in no way have they

successfully completed the ‘contesting of marginality,’ as Hanh claims. Rather, she demonstrates

through one case study of a local educational development initiative, the nuanced performing of

ethnic identity (Schein) functions as a means to re-construct ethnic and female identity not

merely to ‘contest marginality’ but to redefine the very boundaries by which marginality has

been traditionally set forth in the community. Hmong women involved in and affected by this

educational development initiative transform traditionally marginalizing factors within the

community through processes of commodification in order to redefine these boundaries.

Trey Kidwell and Scott Burdick explore resistance in the marketplace. Many of the tourists that

come through the small mountain city are quick to purchase Hmong handicrafts and visit nearby

Hmong villages in tour groups led by Hmong tour guides, yet the tourists find lodging and

purchase food at hotels and restaurants owned by the local Vietnamese. With the ownership of

more stable and profitable business attributed disproportionately to the Vietnamese ethnic

majority, the researchers observe that Hmong have begun to feel as if they are being unfairly

profited from, although tourism industry in Sapa is somewhat dependent on their presence in the

area. Scott and Trey claim that while many Hmong agree that the increased traffic of

international tourists has resulted in increased quality of life, they do not feel that they have

benefited to the same extent as others, especially while contributing to the same profitable

industry that has resulted in their own discrimination.

Brittany Paxton took a slightly different approach, and worked with objects that symbolize

aspects of Hmong culture. She dives into the practice of cross-stitching handicrafts and how the

symbolism of sewing has changed from clothing making to profiting from tourists. Like Trey

and Scott, she notes underrepresentation of Hmong women in the market, but more deeply

explores the two-way relationship between tourism and embroidery. She sees that not only do

tourists demand what Hmong women create, but Hmong women sew what they think tourists

will like, highlighting an intriguing perspective of acculturation.

You Lee, Maie Khalil, and Chee Lor all explore Hmong medical practice. Especially acute for

studies on Hmong health, they have largely been conducted in western countries with significant

populations of resettled Hmong refugees. The overarching themes pervasive within the nursing,

public health, medical, and medical anthropology literature depict the Hmong as a traditional,

static, and homogenous group of people whose cultural beliefs and practices are in conflict with

modern western society, particularly with biomedicine as an explanatory model and institution;

consistently, researchers cite cultural beliefs as the reason Hmong suffer from poorer health

outcomes. Their reasoning assumes that cultural beliefs prevent minority groups from utilizing biomedicine. Structural inequality, racial discrimination, lack of transportation or monetary

funds, and language barriers are typically mentioned secondarily as problems in accessing health

care, if at all. This rhetoric is inherently problematic in that it neglects not only the structural

factors present in everyday life but also by disregarding that the culture of biomedicine does not

allow room for Hmong culture, essentially placing the entirety of blame on the Hmong by the

very framing of the issue. The authors examine new ways to characterize Hmong health care

decisions and portray the rationale behind decisions rather than differences from procedures in

Western medicine.

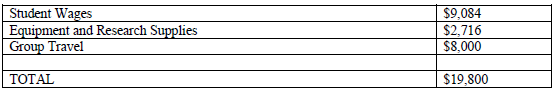

Description of Expenditures

The current MEG grant provided a substantial source of funding to carry out this three months of

mentored fieldwork in Vietnam and China, as well as critical resources for data analysis after the

fieldwork. In total, $9,084 of the MEG Grant went to student wages, including two main

categories. About $6,000 of this total amount went to interpreters in the field. These were

students in the program who received all of the standard training and conducted research like the

rest of the group, but because of their language skills also provided interpretation services for

students who did not speak Hmong or Chinese fluently. An additional $3,084 was used to pay

students on campus to help transcribe, translate, code, and analyze interview and video materials

as they were collected. Student researchers were trained to code and index critical materials for

analysis, and Hmong-speaking RAs on campus were trained to process and analyze these

materials, as well as transcribe/translate them for the field school students to analyze. These RAs

also received valuable research training in this process, and worked with the field school students

throughout the data analysis period. Research supplies purchased on this MEG Grant totaled

$2,716, which included 1) purchasing two iPads for conducting field surveys (total $1,716) on

the Filemaker platform, 2) purchasing two Ultra-High definition portable field cameras (Go Pro

and Contour) and accessories for field recording (total $700), 3) satellite imagery of the sites

where we would be conducting fieldwork ($300). A total of $8,000 of the MEG Grant offset

group travel expenses in the program. This amount covered faculty and student travel and living

expenses during the fieldwork portion of this research. While travel and living expenses

extended way beyond this $8,000, this subsidy made the program expenses much cheaper and

therefore financially more manageable for students enrolled in the program. The difference in

expenses was made up by a Kennedy Center budget and program fees paid by participating

students in the program. The MEG grant was critical in providing critical additional resources

and making this entire field school much more accessible to the students and PI involved, all of

whom benefited immensely from this mentored research program.