Tribett, Taylor

Effects of Tetrabenazine on Basal Methamphetamine

Faculty Mentor: Scott Steffensen, Psychology

It is easy to see how much METH hurts the lives of its users and leads to high costs for society. Methamphetamine abuse is linked to higher healthcare costs, child abuse, and higher rates of theft and incarceration (Dobkin & Nicosia, 2009). Additionally, prescriptions for amphetamines (which are theorized to work by the same mechanisms) almost doubled in the United States between 2006 and 2011 (Sembower, Ertischek, Buchholtz, Dasgupta, & Schnoll, 2013). As the presence of these drugs becomes more widespread, the number of those at risk for abuse and addiction increases as well. In order to develop pharmacological treatments for METH addiction, we must understand the mechanisms by which METH works.

The mesolimbic dopamine (DA) pathway has been identified as one of the key pleasure centers in the brain. The neuro-adaptive changes in this system that occur with exposure to drugs of abuse may be the molecular cause of addiction. The feeling of pleasure is associated with enhanced DA release in target areas of the mesolimbic DA pathway, in particular the nucleus accumbens (NAc). Unnatural dysregulation of DA release may lead to plasticity that governs craving and motivation.

When I began this project, it was understood that METH affects the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2), the protein that packages DA from the cytosol into its presynaptic vesicle, but the importance of VMAT2 was unclear. Under normal biological conditions, VMAT2 pumps free dopamine (DA) out of the cell’s cytosol and into vesicles. When VMAT2 is inactive (usually through pharmacological agents), vesicles lose their pH gradient. Since DA contains a primary amine, it is slightly basic and requires a strong pH gradient to stay in vesicles. Additionally, METH acts directly on the dopamine transporter (DAT) and reverses its function resulting in a release of free DA into the synapse. I sought to better understand the interaction between METH and VMAT2.

It was understood that METH inhibits VMAT2, but it was not yet known if this inhibition was responsible for the surge of DA release associated with METH. It was proposed that, in order to evaluate the mechanism of VMAT2 on DA release, I would use drugs like Tetrabenazine (TBZ) and Reserpine, which are selective inhibitors of VMAT2 (Yao et al., 2011). By treating prepared brain slices containing the NAc with TBZ or reserpine for half an hour, followed by the administration of METH, we expected DA release in the NAc to be comparable to the response due to METH alone. We proposed to measure DA release in NAc using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) which involves the use of microelectrodes with carbon fiber filaments and computer software to measure the electrical current associated with the oxidation-reduction of DA. Slices were to be prepared from wild-type mice and would be treated with 5 μM TBZ or reserpine followed by 5 μM METH.

This was all based on our assumption that VMAT2 is necessary for basal DA release following METH administration, anticipating that treatment with either TBZ or reserpine would enhance the effects of METH, especially at low doses.

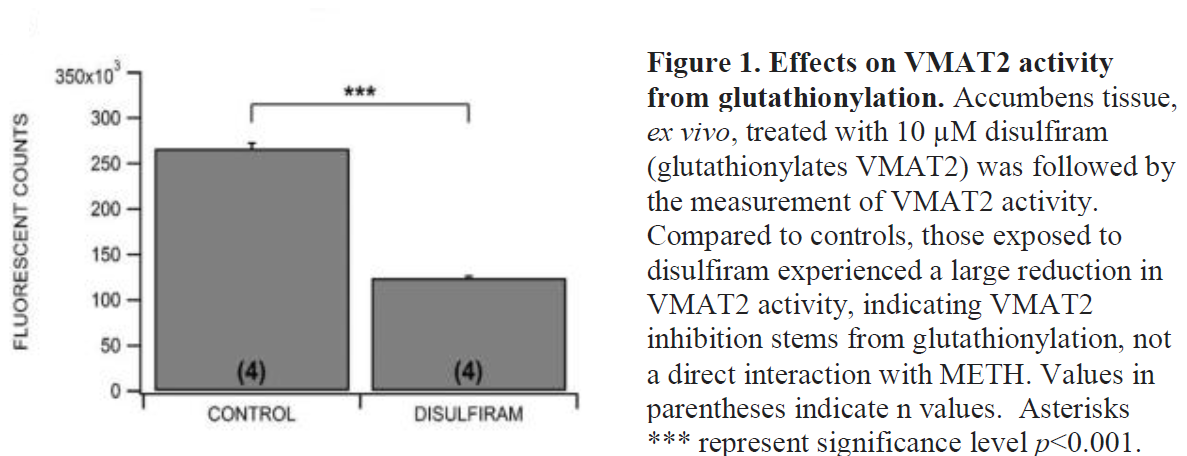

I initially proposed the experiment because it was believed that METH interacts directly with VMAT2 as an inhibitor. However, we found in the course of this study that METH actually induces second messenger pathways. A series of calcium signaling and temporary reactive oxygen species leads to the glutathionylation of VMAT2. This modification is what is responsible for the inhibition of VMAT2 (See Figure 1). On learning this, testing the effects of TBZ was no longer important. To have gone forward with treatment of TBZ, knowing the results would be irrelevant, and would have led to the unethical killing and use of animals.

While it was disappointing to be incorrect in the hypothesis that an interaction between METH and VMAT2 is a key component in the mechanism of METH in the brain, we were still able to take a step forward in understanding the pathway of this debilitating drug. Learning that glutathionylation is responsible for the inhibition of VMAT2 opens the door for more research to be done in this area.

References

Dobkin, C., & Nicosia, N. (2009). The War on Drugs: Methamphetamine, Public Health, and Crime. Am Econ Rev, 99(1), 324-349. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.1.324

Sembower, M. A., Ertischek, M. D., Buchholtz, C., Dasgupta, N., & Schnoll, S. H. (2013). Surveillance of diversion and nonmedical use of extended-release prescription amphetamine and oral methylphenidate in the United States. J Addict Dis, 32(1), 26-38. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.759880