Mike McNeil

Effects of Poverty Simulation: Perceptions of Medical Sociology Students

Gaye Ray, RN, MS, FNP-C, College of Nursing

Introduction

Poverty affects 46.7 million people in the United States. The U.S. Census data show that poverty

rates have increased 2.3% from 2007 to 2014 (DeNevas-Walt and Proctor, 2015). It is shown that

poverty has become a major social determinant of health. Beckles (2011) states that the

socioeconomic circumstances of individuals and the places where they live and work strongly

influence their health. In the United States, the risk for mortality, morbidity, unhealthy behaviors,

reduced access to healthcare, and poor quality of care increases with decreasing socioeconomic

circumstances.

Evidence indicates that students benefit remarkably from classroom and clinical learning

experience in the exploration of poverty, its negative effects on individuals and society, the

health concerns of the impoverished, and the realities of their circumstances (Johnson, Guillet,

Murphy, Horton and Todd, 2015). These vital experiences, including poverty simulations,

provide interdisciplinary students with a greater understanding of poverty (Menzel, Clark and

Darby-Carlberg, 2010).

Methodology

The Global and Public Health Nursing course has implemented the Missouri Community Action

Poverty Simulation as part of its curriculum. During the three hour simulation, the participants,

52 nursing students and 20 medical sociology students (predominantly pre-medical and predental

students), assumed identities and life situations similar to those in poverty, each being

assigned as a member of a diversely configured low-income family. Each student was required to

write a post-participation reflection paper following the simulation.

Qualitative data from the medical sociology student reflection papers was analyzed during

regularly held meetings. During the first-cycle coding processes, segments with topical

similarities were labeled and identified. Using focused coding, a second-cycle coding process

was used to relate categories and identify elements most prominent in the initial coding process.

Themes were identified from recurrent ideas and similar experiences expressed in the reflections.

From this information, we identified excerpts representative of the major themes.

Results

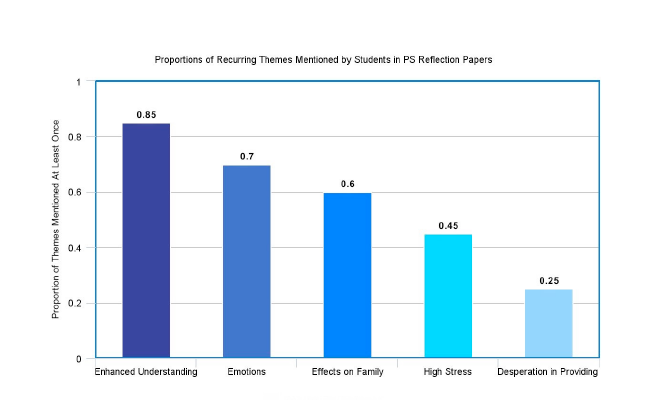

The recurring themes mentioned in the post-participation reflection papers were measured

quantitatively by proportions—comparing the number of papers containing a particular theme to

the total number of papers. Completed analysis of the medical sociology students’ papers

demonstrated that the poverty simulation provokes (1) enhanced understanding of poverty, (2)

deep emotions fostering empathy towards the impoverished, (3) a strenuous effect on the familial

unit, (4) high stress levels throughout the simulation experience, and (5) a sense of desperation in

providing for one’s family.

Discussion

This was the first research of its kind to explore the impacts that poverty simulation has on

medical sociology students. While it is truly impossible to replicate the difficult challenges and

emotions of those who are impoverished, the objective of the simulation is to expose students to

some of the realities of poverty. Poverty simulations are successful techniques that widen a

student’s perspective on the multifaceted and often-misunderstood ecology of poverty, as well as

a change in attitude about the individuals it affects.

Conclusion

Participation in poverty simulations will influence future healthcare providers and motivate them

to become involved with poverty reduction efforts, eradication of health disparities, and reduce

barriers to healthcare for this vulnerable population. Simulation has extraordinary influence on

interdisciplinary health professional students, and thus far our analysis suggests the same for

medical sociology students, in helping them understand health disparities, access barriers, and

social determinants of health.

References

Beckles, G. L., & Truman, B. I. (2011). Education and income—United States, 2005 and

2009. MMWR Surveill Summ, 60, 13-17.

DeNevas-Walt, C., & Proctor, B. (2015). Income and Poverty in the United States:

2014. Current Population Reports, 12-14. Retrieved from

https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60252.pdf

Johnson, K. E., Guillet, N., Murphy, L., Horton, S. E., & Todd, A. T. (2015). ” If Only We Could

Have Them Walk a Mile in Their Shoes”: A Community-Based Poverty Simulation

Exercise for Baccalaureate Nursing Students. The Journal of nursing education, 54(9),

S116-9.

Menzel, N., Clark, M., & Darby-Carlberg, C. (2010). Expanding baccalaureate nursing students’

attitudes about poverty. Presentation at the Western Institute of Nursing. Abstract

retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10755/157286