Caleb Duncan and Landon Wright with John Salmon, Mechanical Engineering

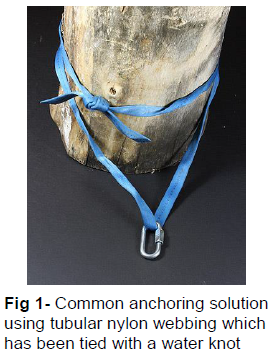

Tubular nylon webbing is an effective and relatively inexpensive anchoring solution for search and rescue groups, fire departments, canyoners, and rock climbers. As an anchoring solution nylon webbing is vital to the safety of anyone who uses it. Serious injury or death will often occur if an anchor fails.

All commercially available webbing is labeled with a breaking strength so that the end user is aware of its limits. This breaking strength value is obtained by the manufacture after running many tensile pull tests of dry webbing. While the dry breaking strength is reported by the manufacture no information, other than statements such as “tensile strength … will be reduced when wet” and “if the webbing becomes frozen it also loses strength,” is given about when wet or frozen webbing will fail1. Due to the often wet and harsh environments in which tubular nylon webbing is used, it is vital for search and rescue groups, firefighters, and climbers to understand how moisture and temperature affect the strength of their webbing. This is what we set out to test.

All the webbing we evaluated was cut to lengths of three feet (approx. 1 m), tied end-to-end to form a loop using a water knot, and pulled until failure. The tensile tester we used to pull the webbing measured the final load at failure and using this data we compiled our results.

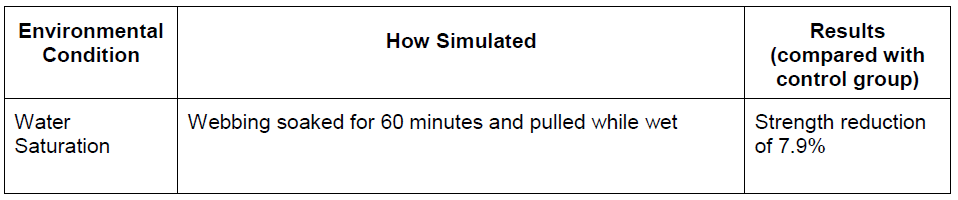

We initiated our testing by pulling 30 dry unused samples as our control group to establish a baseline breaking strength. We then proceeded to test the environmental conditions that were hypothesized to drastically decrease webbing strength on four sets of 20 samples. These conditions, how we simulated them in the laboratory, and the results obtained are shown below.

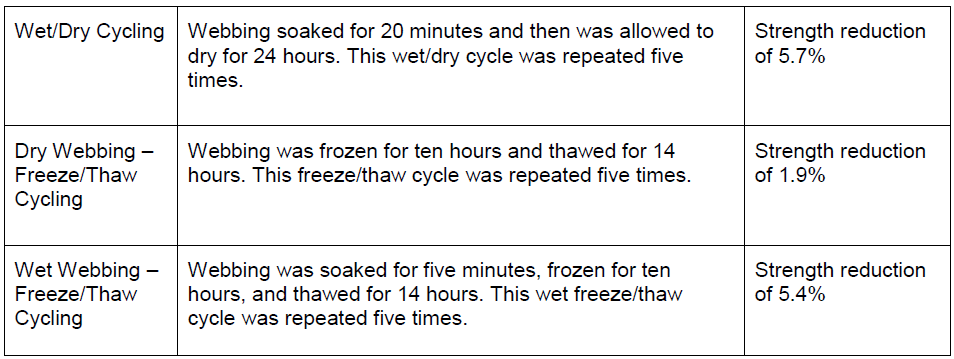

Testing was also performed on 18 webbing samples taken from Cassidy Arch Canyon in Capitol Reef National Park to evaluate and test potential strength reduction in actual use environments. These samples had an average strength reduction of 27.8%.

Our testing shows that webbing exposed to water experiences a statistically significant decrease in its ultimate breaking strength while the effects of freezing are negligible. We also see that webbing which has seen actual environmental use, e.g., the webbing taken from Cassidy Arch Canyon, has a strength reduction of roughly four times that of the weakest condition from the laboratory experiments. This highlights how other environmental factors such as UV exposure, abrasion, and dirt likely have a more profound effect on strength reduction than water and freezing temperatures.

Despite the fact that water has a statistically significant effect on the strength of webbing it makes no difference in real world applications. The climbing webbing used in this study is rated by the manufacture to have a breaking strength of 4000 lbf. (17.7 kN), but our control group averaged a breaking strength of 5019 lbf (22.33 kN). This means that even with the reduction in strength due to water the wet webbing we tested was still able to carry more load than the manufacturer advertises.

We can conclude from the results of our testing that if used in wet conditions tubular nylon webbing will experience a small reduction in strength. This reduction is of little or no consequence to the men and women who rely on webbing for their safety so long as the manufacturer’s instructions and safe anchoring techniques are followed. Our findings also highlight the need for further research in order to determine and quantify the effects that other environmental factors such as UV light, abrasion, and dirt have on webbing strength.

Sources

- Webbing: Use Instructions. BlueWater Ropes, 2015