Mark Johnson and Taylor Nadauld, Department of Finance

Introduction

The availability of higher education is linked to more affluent and prosperous societies. In the United States, policy makers have attempted to make post-secondary education readily available through grants and loans. In the past two decades student loans have exploded to become the second largest segment of consumer debt nationally. The effect that higher loan balances has on students has not been examined extensively. We perform a statistical analysis to demonstrate that when the government increases the supply for federal loans, students take on more credit to pay off more expensive forms of credit. All other effects of loans on post-graduation outcomes that we looked at were not statistically significant.

Data

We obtained both cross sectional and time series data on thousands of post-secondary students in the United States through the US Department of Education. We focus our attention to two sources—first, the Baccalaureate and Beyond survey in 2008-2012 (B&B 2008) and second, the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS 2004, 2008). The B&B 2008 data identifies a subsample of the individuals found in NPSAS 2008 and follows up with survey questions in 2009 and 2012. This survey provides us with data on post-graduation outcomes like salary, graduate school, and debt decisions that are not found in NPSAS. However, NPSAS is important in our study as well because it provides us with a larger sample to more accurately determine the magnitude of the effects

Method

Our analysis in this study focuses on student outcomes when they are supplied with more federal loans. In order to show a causal link between higher loan availability and choices that people make, we implement a statistical method known as regression discontinuity (RD). Regression discontinuity is a useful tool that exploits a difference between two groups of people that are otherwise rather homogenous. For instance, in our analysis we look at students that are 23 to 24 years old with birthdays between October and March who on average look the same in many aspects (gpa, gender, ethnicity, tuition amounts, etc.). However, there is one distinct difference between the 23 year-olds born in January and the 24 year-olds born in December—The government recognizes the 24 year-olds as independents when filling out forms for federal aid and hence qualify for more loans. This difference acts as a natural experiment where some people are “randomly” assigned to a control group while the other is assigned to the treatment group. We then measure the effect that this policy has on average borrowing amounts and the subsequent changes in student outcomes.

This specific design where birthdays are used to determine the treatment group was used by Constantine Yannelis (2015) in his job market paper “Asymmetric Information in Student Loans”. We

were interested in looking at default rates as well, but Yannelis exhausts that avenue in his job market paper. The RD design will lead to consistent and unbiased results as long as the running variable (birthday) is not correlated with any other omitted variables. This was tested in the form of McCreary tests for many of the observable characteristics which leads us to conclude that our estimates are likely to be consistent and unbiased.

Results

The regressions are performed in two stages where the first stage reports the magnitude of changes in borrowing amounts near the policy cutoff and the second stage reports the magnitude of change in various outcome variables. It is important to note that in addition to relaxed credit constraints, independent students are also more likely to qualify for pell grants which could have some influence on our outcome variables as well. There is no way to control for the increase of pell grants so we must accept that we are jointly testing the increase in borrowing and grants.

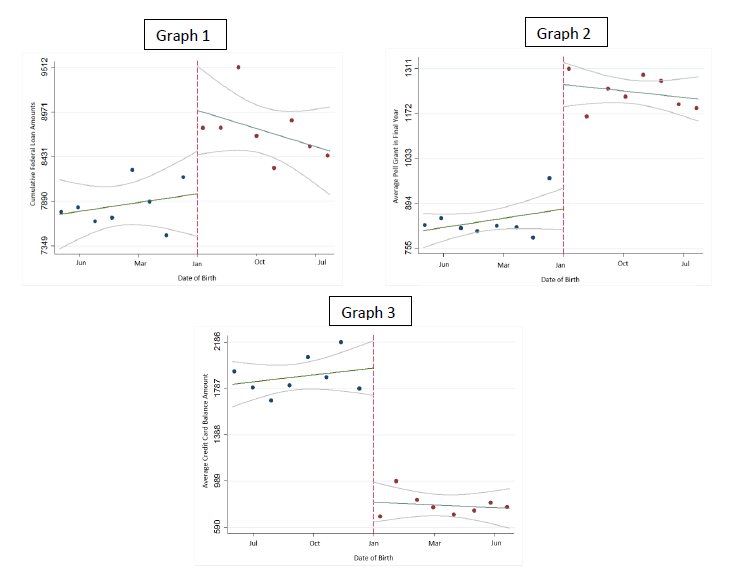

As can be seen in graphs 1 and 2, there is a sharp increase in both borrowing and grants at the birthdate cutoff for automatic independent status. The estimated average coefficient for cumulative federal loans increases by $951 with a significant 2.26 z-score suggesting that with over 95% confidence the true mean is not zero. Pell grants see an increase as well of $350 with z-score of 6.67 also well above the 95% confidence interval.

The second stage produced interesting results as well. Interestingly many of the variables we tested showed that there was no significant change for students that received over $1200 of additional aid. That is to say that if the government were to offer more aid to students it would likely not effect things like GPA, hours worked during the school year, time to graduation, choosing to study abroad, etc. There was, however, one variable that was influenced greatly and that is the average balance that students have on their credit cards. As can be seen in graph 3 there is a dramatic drop in the balance the students carry if they are in the “treatment” group, the group that received an average of over $1200 dollars in loans and grants. The magnitude of this drop is approximated to be $565 with a highly significant z-score.

Conclusion

The results of this study do not necessarily lead us to any conclusion on the correct or efficient policy on the effectiveness of increasing federal student aid. It is clear that when federal aid is expanded, the additional loan and grant amounts help to reduce balances on student credit cards. Whether or not the balances on credit cards are school related expenses cannot be determined with the data we have available, but could be an avenue for further research. If it is the case that many students spend federal aid on new cars, plastic surgery, or new technology then policy makers may want to reconsider how to implement the supply of credit to students. As for actual student outcomes, both during postsecondary and after graduation, it appears that government loan expansion has little to no effect using our statistical methods. It is possible that we do not observe any significant effects due to the limited number of observations in our sample.

Bibliography

- Jesse Rothstein, Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Constrained after college: Student loans and early-career occupational choices”, Journal of Public Economics, Volume 95, Issues 1–2, February 2011, Pages 149-163

- Robert Sauer, “Educational Financing and Lifetime Earnings”, Review of Economic Studies (2004) 71 (4): 1189-1216.

- Christopher Avery, Sarah Turner, “Student Loans: Do College Students Borrow Too Much—Or Not Enough?”, Journal of Economics Perspectives, Volume 26 (1) Winter, Pages 165-192

- David Lucca, Taylor Nadauld, Karen Shen, “Credit Supply and the Rise in College Tuition: Evidence from the Expansion in Federal Student Aid Programs”, No. 733. Staff Report, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2015.

- Mark Dynarski, “Who defaults on student loans? Findings from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study”, Economics of Education Review, Volume 13, Issue 1, March 1994, Pages 55-68

- Felicia Ionescu, “The Federal Student Loan Program: Quantitative implications for college enrollment and default rates”, Review of Economic Dynamics, Volume 12, Issue 1, January 2009, Pages 205-231

- Constantine Yannelis, “Asymmetric Information in Student Loans”, Job Market Paper, http://web.stanford.edu/~yannelis/JMP.pdf