Hannah Whipple, Bryan Stewart, and Doug Prawitt; School of Accountancy

Introduction

As watchdogs of public companies’ financial reporting, auditors have the responsibility to attest whether a firm’s financial statements fairly represent its finances. As such, auditors are subject to professional standards to ensure high-quality audits. At times, however, auditors fail to meet these standards with their actions. Such actions, “which reduce evidence-gathering effectiveness inappropriately” (Malone and Roberts 1996), are referred to in the academic research literature as reduced audit quality acts (RAQAs). RAQAs increase the risk of inappropriate or misleading audit opinions, which can harm investors, lenders, and other parties, and which often lead to litigation. We seek to determine how jurors’ judgments in such cases are affected by conditions commonly surrounding RAQAs. We hypothesize that jurors are more likely to find the audit firm at fault when the RAQA is directly related to the area of misstatement than when it occurs in an unrelated area, as well as when the auditor is a higher-level partner rather than a lower-level senior.

Methodology

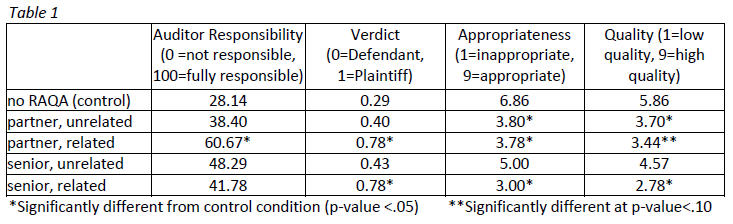

We utilize a 2 x 2 + 1 experimental design, wherein we randomly assign participants to one of five conditions (see Table 1). Participants read a case, adapted from Kadous and Mercer (2012), in which an audit firm, Baylor & Grimble LLP, is sued by Mason Pension Fund. Mason was a major investor in Ocean Manufacturing, a hypothetical, publicly traded company that declared bankruptcy in 2015 despite having presented healthy financial statements. Subsequently, it was found that there was a misstatement in the area of inventory that was not detected by the auditor, and that, except in the control condition, the auditor committed an RAQA. That is, the auditor signed off on audit procedures directly pertaining to the inventory count (related area) or the fixed asset count (unrelated area) before it was fully completed.

Participants indicate the extent to which they believe Baylor & Grimble is responsible for Mason’s losses and rate the quality and appropriateness of the audit. They also give a verdict, in favor of either the plaintiff or the defendant. A manipulation check question asks if Baylor & Grimble fulfilled its responsibility to fully audit the company’s inventory account. Finally, participants supply demographic information.

Due to the legal implications of our case, we solicited the help of John Treu, a licensed attorney and CPA, who is researching the role of expert witnesses and optimal demographics for participants to best represent an actual jury in an audit trial. Our preliminary results come from a sample of students and professionals who responded to an anonymous link to our pilot survey on Qualtrics. Once our instrument is finalized per the legal research, we will solicit participants through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk).

Results

We gathered results from 42 participants, of whom 62 percent are female, with an average age of 31. Our manipulation check question shows that eight individuals failed to correctly identify whether the audit firm had fully completed its audit of inventory; seven of these errors were in the unrelated (fixed asset) conditions.

Table 1 shows the average responses across the various conditions. A series of analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests shows that no conditions are significantly different from each other at the α=.05 level; two are significant at the α=.10 level.

Discussion

In analyzing our results, it is important to note the lack of representativeness of our small sample. At least seven participants are accountants or accounting students; in an actual jury case, these would likely be excluded from the jury, as they present a bias against holding the auditor legally liable. This bias is reflected in our results. Most conditions were significantly different from the control for the Appropriateness and Quality questions; however, for the Responsibility and Verdict questions, there was little difference from the control. This suggests that whereas the participants recognized a lower level of appropriateness and quality when an RAQA was present, they were hesitant to hold the auditor legally liable. Importantly, the exception to this was when a partner was involved in an RAQA directly in the area of the misstatement.

The general lack of significance across conditions may suggest confusion as to the importance of the differences presented, especially given the high rate of manipulation check failure in the unrelated condition. However, this could actually be representative of the outcomes of a real jury case, given the high degree of technicality in the issues presented and a low level of understanding of auditing in typical juries.

Conclusion

We conducted a preliminary pilot experiment to discover how jurors hold auditors accountable for RAQAs under different circumstances. We find that participants recognize when auditors perform low-quality audits, but are hesitant to hold them legally liable, and do not differentiate their ratings of the audit based on the area in which the RAQA was committed or by whom, with the exception of an RAQA committed by a partner in the area in which the misstatement was located. Based on these results, we plan to clarify our survey, collect data from a larger and more representative sample via MTurk, and conduct more in-depth analysis. If our initial results hold, they will be an indication of an area of weakness in our judicial system regarding how low-quality audits are litigated, and will inform researchers and practitioners about how RAQAs are likely to affect jurors in different circumstances.