Chelsi Tolbert and Jennifer Wimmer, Teacher Education

Introduction

It is an unarguable fact that literacy instruction is one of the most vital aspects of elementary education. Without literacy, knowing how to read and write, students will find success in the “real” world difficult to come by. Traditionally, the focus of literacy instruction has been linked to giving students the tools they will need once out of school, however recent studies have begun to look more critically at what literacies students are bringing into the classroom. These investigations look explicitly at community literacy, specifically, the funds of knowledge that students learn from their homes and communities that may not align with the traditional idea of “academic literacy,” yet still allow for literacy to be functional in everyday life. Pahl & Rowsell state, “Literacy can be found embedded in popular songs, within electronic equipment and software, within malls and signage” (2012, p. 56-57). This idea that literacy and understanding can be found in non-traditional print texts has the potential to drastically change the way literacy is taught in school. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, during the 2011-12 school year, there were an estimated 4.4 million English language learners (ELLs) in the United States (2014). If teachers can identify the way literacy is being used by their students at home and in their community practices (i.e. church, after school programs, household activities, etc.) they will be better able to make sense of the way children use literacy in school (Pahl & Rowsell, 2012, p. 56). Furthermore, understanding how home literacy affects how children use and understand literacy in school can help teachers bridge the gap between home and school. Given an increase in student diversity in classrooms, it is essential that teachers come to understand students’ backgrounds, funds of knowledge, and personal experiences. A large body of literature suggests that students’ lives are full of literacies that they developed in their homes, neighborhoods, and communities. Community literacies encompass the “social, cultural, and historical contexts of literacy practice, one of those contexts being the communities in which students live and work outside of school” (Moje, 2000, p. 79). There is a call for the integration of students’ funds of knowledge—which provide a means for students to make meaning of the world—into classroom literacy instruction, thereby allowing students to transfer home literacies to school and vice versa. Current research suggests that teachers would do well to acknowledge and build upon the literacies students develop outside the classroom. However, it is not enough to learn about the communities from which students come; teachers need to collectively seek to understand, appreciate, and utilize this information. Literacy is not something that is acquired only within the four walls of the classroom. Students are growing up in an increasingly diverse world and have opportunities to engage with text, both print and non-print, ion a daily basis. Teachers can better help children learn and acquire literacy when the texts and literacies discussed in the classroom are connected to the lives of the children. However, teachers may be unaware of the texts and literacies that children encounter outside of school. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify and describe the texts and literacies students engage with on a daily basis.

Methodology

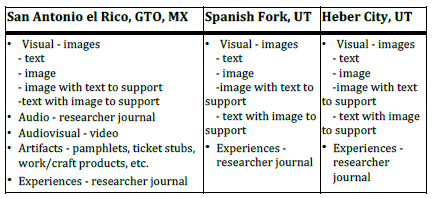

Data was gathered in three rural communities, San Antonio el Rico, Guanajuato, Mexico, Spanish Fork, Utah, and Heber City, Utah, beginning summer of 2015 and concluding in June 2016. Data collection focused on the available texts in communities (e.g. classroom, school, neighborhood, and community) and included photographs, artifacts, and a researcher journal. I began data collection during the summer of 2015 when I had the opportunity to live and teach in San Antonio el Rico, a small, rural rancho in the central Mexican state of Guanajuato, for three months. The two communities in Utah were also rural locations where, as part of the Elementary Education program, I was placed as a pre-service teacher during my practicum semesters.

Results

On the surface the main differences experienced in this study were linguistic (English vs. Spanish) and cultural (values, perspectives, priorities, logistics, etc.). However, deeper analysis of the data collected provided an insight that could help teachers of ELLs. On average, signs and advertisements in San Antonio el Rico utilized more images with supporting print than the same genre of signage in Spanish Fork and Heber City. The texts found in the US communities were noticeably more print based with images as a support; especially in areas closer to  schools, the literacies needed to understand the messages were increasingly print based. Along the same lines, non-print-based literacies were much more prevalent in rural Mexico, and I noticed various auditory literacies such as the need to understand and distinguish different bells and horns in order to know when to go to church, when to catch the bus, and when to buy more propane or tortillas. The same tasks in the US, buying food, going to church, using public transportation, is done by reading printed schedules and/or revolve around a person’s ability to use their own vehicles to take them to appointments and run errands. One of the greatest difficulties in analyzing the texts and literacies I documented was distinguishing between what differences were comparable and which were not, due to cultural factors. As a teacher I realized that regardless the cultural

schools, the literacies needed to understand the messages were increasingly print based. Along the same lines, non-print-based literacies were much more prevalent in rural Mexico, and I noticed various auditory literacies such as the need to understand and distinguish different bells and horns in order to know when to go to church, when to catch the bus, and when to buy more propane or tortillas. The same tasks in the US, buying food, going to church, using public transportation, is done by reading printed schedules and/or revolve around a person’s ability to use their own vehicles to take them to appointments and run errands. One of the greatest difficulties in analyzing the texts and literacies I documented was distinguishing between what differences were comparable and which were not, due to cultural factors. As a teacher I realized that regardless the cultural ![]() differences and factors that may not appear to cross over, the texts and literacies of any culture are important to take note of, as they will influence the students coming from environments and communities hosting similar literacies. Although the three communities I spent time and taught in were all very different, there were similarities in the texts available to the public. Many advertisements used images with supporting text, which seemed to be easily read and comprehended by all. In both Utah communities, restaurants, stores, and businesses found in town used logos and symbols. Due to the cultural difference in how shopping is done in rural Mexico versus in the US, similar establishments are not labeled the same way. However, the similarity here lies in how they are distinguished. In rural Mexico, many of these establishments are part of peoples’ homes. When identifying business-homes shoppers look for any Coca Cola symbol. Although the texts available in the three communities varied greatly, the greatest similarity my research revealed is that no matter what country, and no matter how rural the community, texts are still found and literacies are still developed.

differences and factors that may not appear to cross over, the texts and literacies of any culture are important to take note of, as they will influence the students coming from environments and communities hosting similar literacies. Although the three communities I spent time and taught in were all very different, there were similarities in the texts available to the public. Many advertisements used images with supporting text, which seemed to be easily read and comprehended by all. In both Utah communities, restaurants, stores, and businesses found in town used logos and symbols. Due to the cultural difference in how shopping is done in rural Mexico versus in the US, similar establishments are not labeled the same way. However, the similarity here lies in how they are distinguished. In rural Mexico, many of these establishments are part of peoples’ homes. When identifying business-homes shoppers look for any Coca Cola symbol. Although the texts available in the three communities varied greatly, the greatest similarity my research revealed is that no matter what country, and no matter how rural the community, texts are still found and literacies are still developed.

Discussion

This study brought to light a few issues regarding the imbalance of what literacies students are taking to school with them and what literacies are being reinforced or taught in the classroom. Educators who take the time to understand their students’ backgrounds find their ability to help accommodate and more effectively reach their students in a meaningful way. Is that enough? Is it possible to really understand a student’s background without identifying what they encounter everyday in their out-of-school environments? After analyzing the literacies available in three different rural communities, I don’t believe so. Students spend roughly five years being exposed to texts and becoming literate in a variety of ways before entering formal schooling. Teachers who look at printbased texts as the only “literacies” their students know or need-to-know are limiting their potential for meaningful instruction as well as limiting their students’ ability to find academic success. Tapping into the funds of knowledge each student brings with them to school, using images either as a support to print text, or images being supported by print text, using hobbies, interests, traditions as context or examples of academic information can radically help students build bridges to comprehension.

Conclusion

This study is not only relevant to teachers across the globe, but is very relevant to me personally as I work my way from pre-service to in-service teaching. I am currently finishing my Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages minor, and this project has prepared me to reach students from diverse backgrounds. This experience taught me that by understanding your students and the community in which they live, educators will more effectively teach their students in a way that is relevant, allowing connections to be made to the real world, and information internalized and remembered.

Scholarly Sources

Moje, E. B. (2000). Critical issues: Circles of kinship, friendship, position, and power: Examining the community in community-based literacy research. Journal of Literacy Research, 32(1), 77-112.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2014). English language learners. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgf.asp

Pahl, K. & Rowsell, J. (2012). Literacy and Education. (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.