Gary Burlingame, Psychology

What follows is brief summary of how we used the MEG funding to support a 3-year multi-site randomized clinical trial involving students in group treatment at three Utah counseling centers—BYU, SUU & USU. We’ve organized the summary using the five report guidelines listed on the ORCA website.

Evaluation of how well the academic objectives of the proposal were met

Previous research from our lab has shown that the therapeutic relationship in group therapy is one of the best predictors of improvement for patients treated for a variety of psychiatric disorders. These empirical findings led to an international cooperation to develop the Group Questionnaire (GQ) with researchers from Germany and Norway. We’ve used the GQ to show that group leaders, like their individual therapist counterparts, are poor predictors of how their patients perceive the therapeutic relationship. Therefore, this project was the penultimate study to empirically test the effect of providing feedback to group leaders about the quality of the therapeutic relationship on their patients symptomatic change. More specifically, the academic objectives were to directly test the effect of providing and withholding GQ and OQ-45 (therapeutic relationship and symptomatic change, respectively) feedback on cases identified to be at risk for treatment failure. The therapists served as their own control running two simultaneous groups with one randomly assigned to the therapeutic feedback condition and the other having feedback withheld. The study took an extra year than anticipated, with two years of group treatment and three total years of data collection, but we were successfully able to achieve our objective.

- The study has already supported two Ph.D. dissertations in the Clinical Psychology program, one in the Counseling Psychology program and a master’s thesis in Clinical Psychology. Thus, we exceeded our initial academic objective of supporting 2 dissertations.

- The above doctoral students mentored slightly more undergraduate students than anticipated (5 instead of 4). Three of these undergraduate students were admitted into graduate programs in clinical psychology and marriage and family therapy. The two remaining students are currently applying for graduate school admission this year. Thus, we achieved our second academic objective of mentoring undergraduate students and supporting them in achieving their next educational objective; doctoral and master’s degrees. One undergraduate, Rebecca Janis, is in a top notch lab at Penn State and intends to return to BYU as a professor. If she does, she will be the 4th undergraduate from our lab to return as a professor in our department.

Evaluation of the mentoring environment

The mentoring environment on the current project was collaborative, supportive, and professional. Students were involved in all aspects of the research including participating in a weekly faculty research lab meeting that modeled the nuts and bolts of running a randomized clinical trial. The four Ph.D students also received weekly (sometimes daily) supervision from Dr. Burlingame since each was responsible for supporting up to 8 Ph.D. level psychologists providing treatment for the study. Nearly 450 patients were treated in 69 groups with the average group lasting for nearly a semester. Since weekly data on multiple measures were collected from each patient and therapist in the study, daily monitoring was required. Each doctoral student mentored at least one undergraduate student who supported the aforementioned data collection. Overall, the mentoring environment provided graduate and undergraduate students with an opportunity to observe and participate in a productive university research lab which provided opportunities for training, questions, and growth. Students were encouraged to produce timely, quality work, and were met with understanding and support in the face of challenges. As such, the environment facilitated student growth with opportunities to learn and be challenged while fostering a dynamic of safety and encouragement.

List of students who participated and what academic deliverables they have produced or it is anticipated they will produce

- Doctoral Students

- Sean Woodland– Sean is a recent graduate from BYU’s Clinical Psychology Ph.D. program and assisted in the current study. He completed his dissertation with data collected during the first year of this study. It was a pilot study exploring leader use of the GQ. Since researching in Dr. Burlingame’s lab, Sean has successfully completed an internship at El Paso Psychology Internship Consortium and was hired at Kaiser Permanente in Roseville, CA. Sean made four national and international presentations using data from the study.

- Kait Whitcomb– Kait is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Clinical Psychology program at BYU and has been working on this project since its beginning. Her dissertation research is a replication of Sean Woodland’s based on the data from the second year of data collection. Once complete, her dissertation will help Dr. Burlingame and Dr. Beecher to create a moderator variable used to determine how leader feedback use influences client dropout, and scores on the GQ and OQ. Like Sean, Kait has made four national and international presentations using data from the study.

- Jen Jensen– Jen is a current second-year in BYU’s Clinical Psychology Ph.D. program. She is using the data from this project to support her masters thesis in the doctoral program, which will examine what is lost in terms of psychometrics and clinical utility if the GQ is shortened.

- Mindy Pearson—Mindy is an advanced doctoral student in BYU’s Counseling Psychology Ph.D. program. She is using the data from this project to support her dissertation which uses the GQ and OQ as predicted variables and the Group Readiness Questionnaire (also developed at BYU) as a predictor variable to support better selection and placement of potential group members treated in counseling centers.

- Michael Williams– Michael is a third-year in BYU’s Counseling Psychology Ph.D. program and is working toward a career in academia and research. He participated in the data collection and monitoring process but did not use the data to support independent research.

- Undergraduate Students

- Rebecca Janis– Rebecca participated in multiple research projects conducted in Dr. Burlingame’s lab and was a core data quality monitor for the study. She published and presented several articles and papers during her time in the lab and is now a second-year Ph.D. student at Pennsylvania State University. She continues to collaborate on research projects with Dr. Burlingame. Her intention is to become a research and teaching professor and return to BYU’s clinical psychology program which currently has no female faculty.

- Jyssica Seebeck– After researching in Dr. Burlingame’s lab on this project as well as others, Jyssica was successfully admitted into a PsyD graduate program at Seattle Pacific University, where she is currently a second-year student. She, like Rebecca, published and presented several articles and papers during her time in the lab.

- Thomas Childs– Tommy contributed to three research projects conducted in Dr. Burlingame’s lab, after which he was successfully admitted into a Marriage and Family Therapy Master’s program at Kansas State University.

- Jordan Rands– Jordan assisted in data collection for this project. With a letter of recommendation from Dr. Burlingame, he was admitted to Teach America supporting underprivileged school children in Chicago. He’s currently applying to Ph.D. programs in clinical psychology with the intent of becoming a clinician.

- Kevin Baer– After contributing to this research project, Kevin solidified his future career goals of becoming a psychiatric nurse and plans to apply for graduate school after completing his undergraduate education next year.

Description of the results/findings of the project

The cleanup and merging of the final data set was completed at the end of fall semester 2015. The two arms of the prospective data collection phase of the study invited 455 group members to participate with over 95% (433) consenting to participate; an unusually high percentage for our field. Of these, 87% (376) provided sufficient data (three repeat administrations) to address the research hypotheses. These individuals were treated in 59 unique groups that produced 69 semester long group episodes of care that were led by 17 Ph.D. psychologists working in one of three university counseling centers (BYU, USU & SUU). The third arm of the data included a matched (symptom severity and gender) sample drawn from an archival data based of BYU OQ-45 feedback studies composed of 6151 patients who were studied in one of 6 randomized clinical trials conducted under the supervision of Michael Lambert. With data collection, auditing, and cleanup just completed, we provide a brief summary of analyses conducted on the first year of data collection to illustrate our primary finding that feedback in group treatment appears to replicate findings from past individual therapy feedback studies; particularly with respect to changes in patients who are experiencing therapeutic relationship failure.

Question 1—Does providing a group leader with therapeutic relationship feedback change the number of clients in their groups who signal as treatment failures?

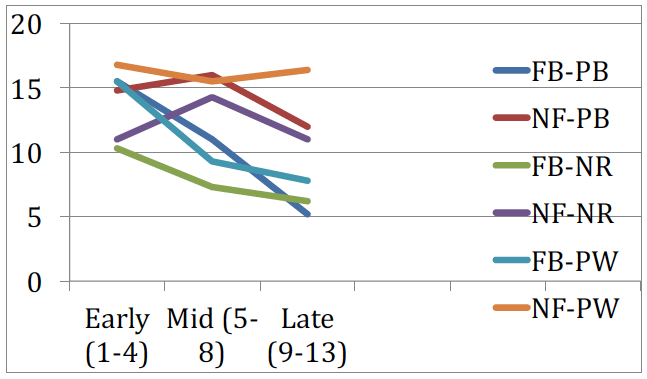

Each group leader received treatment failure alerts on half of their groups provided by the three GQ subscales. The alerts can be understood as follows: (a) positive bond (PB) alerts the therapist to extremely low levels of empathy, warmth and acceptance; (b) positive work (PW) alerts the therapist to a failure to achieve a patient’s treatment goals and; (c) negative relationship (NR) alerts therapist to high levels of empathic failure, conflict and alliance rupture. Using about a third of the data we found that over a semester group episode, group leaders who received treatment failure alerts (i.e., feedback—FB) from the GQ were able to significantly reduce their occurrence over time on all three GQ subscales when compared to identical groups that they led where they received no feedback (NF). Figure 1 graphically portrays this effect; the largest effects were found on the negative relationship subscale.

Figure 1

Proportion of relationship failure alerts X GQ subscale over time

Question 2—Does providing a group leader with failure alerts lead to positive change in the therapeutic relationship in the treatment sessions that immediately follow the alert?

Our past research demonstrated that group therapists are unaware of therapeutic relationship failure as perceived and reported by group members. It also showed that these perceived relationship failures do not spontaneously disappear, but in fact lead to 0 5 10 15 20 Early (1-4) Mid (5- 8) Late (9-13) FB-PB NF-PB FB-NR NF-NR FB-PW NF-PW poor outcomes and early dropout. Thus, our prediction was that when treatment failure occurred in a given session, the most likely outcome in sessions that immediately follow is a continued state of treatment failure; i.e., a GQ alert. For instance, if a group member alerts on the positive bond (PB) subscales on session 5 by reporting extremely low levels of empathy, warmth and acceptance, we would predict that this risk would remain in sessions 6 and 7 since the leader is likely unaware of these perceptions. On the other hand, if a therapist is alerted to this therapeutic relationship failure in session 5, we would predict that they would engage in risk reduction interventions in sessions 6 and 7 leading to higher levels of empathy, warmth and acceptance, thereby reducing the risk of relationship failure. In short, we predicted a pattern of risk reduction for the groups where the leaders received feedback, and an absence of risk reduction for groups where the same group leader did not receive feedback. We examined this prediction by the three subscales of the GQ on the two sessions immediately following a relationship failure alert. We looked at both sessions combined using a multivariate analysis and also looked at the two sessions in a univariate fashion.

- Negative relationship (NR)—this GQ subscale was the only one that produced a statistically significant multivariate effect. Risk reduction occurred 75% of the time in the feedback condition when we examined the NR subscale for the two sessions immediately following an alert. However, in the absence of feedback there was no risk reduction; clients continued to be at risk for therapeutic relationship failure. Interestingly, for the 25% of session pairs in the feedback condition that did not produce multivariate significance, risk reduction was achieved by the second session. Stated differently, risk reduction was achieved in 100% of alert cases in the feedback condition, but when alerts occurred in latter phases of group treatment (session 8 & 10) it took two sessions for risk reduction.

- Positive bond (PB)—there was no multivariate effect for feedback for PB alerts, 75% of the univariate analyses produced risk reduction. Stated differently, alerts that involve extremely low levels of empathy, warmth, and acceptance take two sessions after a therapist receives feedback to reverse risk. On the other hand, there was no risk reduction for any session pair for the no feedback condition; risk was predicted for every session.

- Positive bond (PB)—there was no multivariate effect for feedback for PB alerts, however, 75% of the univariate analyses showed risk reduction. Stated differently, alerts that involve extremely low levels of empathy, warmth and acceptance take two sessions after a therapist receives feedback to reverse risk. On the other hand, there was no risk reduction for any session pair for the no feedback condition; risk was predicted for every session.

- Positive work (PW)—like PB, there was no multivariate effect for feedback for PW alerts, however, 63% of the univariate analyses demonstrated risk reduction. Stated differently, alerts that indicate a failure to achieve a patient’s treatment goals take two sessions to reverse risk. On the other hand, there was no risk reduction for 75% of session pairs for the no feedback condition.

Summary

Our initial analysis of therapeutic relationship feedback in group treatment replicates and extends findings from the individual literature. Using group leaders as their own controls, we found the strongest support for leader feedback with negative relationship alerts. This is particularly important because past research has linked these type of alerts to the clients dropping out of treatment prematurely and posting poorer rates of overall symptomatic improvement. In short, leaders who receive alerts on this GQ subscale were on an aggregate level able to reverse the risk within one treatment session. A similar, but less robust effect was found on the other two GQ subscales at a univariate level. Three-fourths of the time leaders who received alerts on the PB subscale are able to reverse risk on an aggregate level within two sessions and 63% of the time for PW alerts. We see this as promising, and now that our data set is complete and merged with a no feedback condition for the OQ, we are now ready to begin to explore the effect of progress and therapeutic relationship feedback in group treatment. We are very appreciative of the support our students received in producing this data set. Our lab has a 30-year history of mentoring both undergraduate and graduate students with 10% of our department faculty having been mentored in what we believe is a diverse and productive learning environment.

Description of how the budget was spent

—Total awarded: $18,500

- $11,000 was dispersed as graduate research payment to Kait Whitcomb’s work on the moderator variable that will be used to determine if the way leaders used the GQ feedback influences client dropout or scores on the GQ or OQ.

- $7,500 was used to fund client participation in the study (the $10 signing bonuses and $5 per set of GQ and OQ data provided).