Jameson Brau and Faculty Mentor: Larry Nelson, College of Family, Home, and Social Sciences

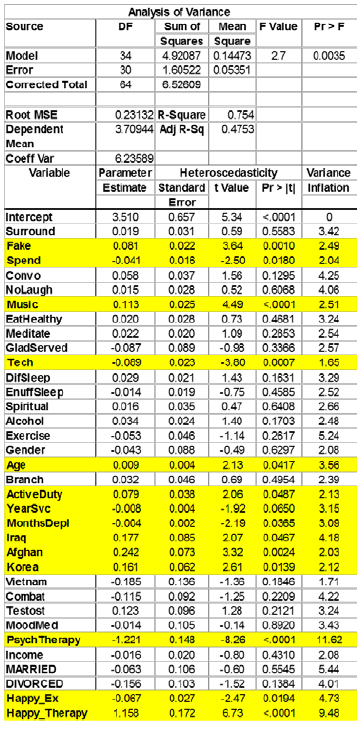

In this study I design a survey instrument and construct a data panel from the responses of a sample of US veterans. As part of the survey, I estimate the level of happiness each veteran exhibits using the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire. The Oxford scale consists of 29 questions and uses a Likert scale that ranges from a low of one to a high of six. The average is typically around 4.3 (Hills and Argyle, 2002). The average happiness score for my sample of 76 veterans is 3.73. After measuring the happiness level, I ask 30 additional questions driven by the literature to determine the factors of veteran happiness. Next, I conduct Spearman Correlation tests, t-tests for equality of sample mean divided on the median of the happiness score, and a multivariate ordinary least squares model with all of the explanatory factors. I find significance for: four holistic happiness variables (faking happiness (+), spending money on loved ones (-), listening to music often (+), and using technology often (-)); one demographic variable (Age (+)); six military-related variables (active duty service (+), years of service (-), months deployed (-), service in Iraq (+), Afghanistan (+), Korea (+)); and two intervention variables (psychotherapy (-), exercise (+)). Testosterone treatment is not statistically significant.

Specifically, I find over a dozen variables that impact the level of happiness in veterans.. Factors that are positively correlated with Happiness are: faking to be happy when you are not, listening to music often, age, serving on active duty, serving in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Korea, and exercise for a given level of happiness. Factors that are negatively correlated with Happiness are: spending money on friends, using a lot of technology, serving longer periods in the military, being deployed for longer periods in the military, and seeking psychotherapy either unconditionally or conditioned on happiness levels. The somewhat controversial use of testosterone treatment to help depression showed no significant impact in the tests.

Specifically, I find over a dozen variables that impact the level of happiness in veterans.. Factors that are positively correlated with Happiness are: faking to be happy when you are not, listening to music often, age, serving on active duty, serving in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Korea, and exercise for a given level of happiness. Factors that are negatively correlated with Happiness are: spending money on friends, using a lot of technology, serving longer periods in the military, being deployed for longer periods in the military, and seeking psychotherapy either unconditionally or conditioned on happiness levels. The somewhat controversial use of testosterone treatment to help depression showed no significant impact in the tests.

My results are limited in that they show correlation and not causation. That is, I cannot discern if people who are already happy like to meditate or if meditation helps people become more happy. The result on seeking psychotherapy is an example where the causation and correlation are particularly important. Future research can explore the topic of happiness activities on happiness levels by trying to establish causality and not just correlation. Given this limitation, my study shows that happy people are significantly correlated with specific activities and experiences in their lives and suggests that perhaps seeking these happiness activities would be a good idea for people seeking higher happiness levels.

Primary Regression Results are in the table to the right.