Preston Christensen and Cynthia Hallen, Linguistics

Abstract

Patronymic naming is very common in parts of Mozambique but there has possibly been no formal documentation of this practice prior to this study. Patronymic naming involves the passing of the father’s name to the children and is not to be confused with patronymic surnames. The research was conducted in the City of Quelimane, Mozambique and consisted of two parts, quantitative and qualitative.

The quantitative research was conducted by gathering approximately 500 names from church records from two parishes of the Catholic Church in Quelimane. It shows that patronymic naming is used by the majority of people in Quelimane. The data shows the variation of the use of patronyms from sample years both before and after independence from Portugal in 1975. The qualitative research consisted of 27 interviews from three neighborhoods in Quelimane. It brought perspective to the quantitative data while still leaving many questions unanswered. Teknonyms, or the calling of parents by the child’s name, is quite common informally in Mozambique, especially in the home and neighborhood and generally follows the pattern of pai de [child], or mãe de[child]. It was found that the use of this naming pattern is both practical and culturally significant in that it acknowledges the parent’s status in the community. The practice of naming the children with the names of ancestors was also observed. Although this pattern seems to be used rather intermittently, it was suggested by many that this is the more traditional method of assigning the first given name.

Methods

As previously mentioned, this study consists of two parts, a quantitative portion and a qualitative portion, both of which were conducted in the city of Quelimane, in the province of Zambezia, Mozambique. The research was conducted under the direction of the IRB of Brigham Young University.

Originally, it was the researcher’s intent to gather the quantitative data from the Civil Registry of the City of Quelimane, however a lack of cooperation from the provincial government required that the data be gathered elsewhere. With the help of clergyman from the Sé Catedral Parish and the Familia Sagrada Parish 505 baptismal records from representative years were analyzed for the presence of the patronymic naming pattern. Amid the wide variety of naming patterns used, it was necessary to come up with a discriminating definition of what was to be counted as patronymic and what was to be counted as a different pattern. A surname was considered patronymic if the father’s full name was included at the end of the child’s name regardless of whether one or more name came before the patronym. It was also considered patronymic if only part of the father’s full name was included in the final of the child’s name, as long as the patronym was only reduced by final names and not middle or first names.

For the qualitative research, 27 interviews were conducted in three neighborhoods of Quelimane. Neighborhoods were selected in a stratified sampling representing three different socio-economic backgrounds. 10 interviews were conducted in primeiro de maio, which represents the “middleclass”, 8 interviews were conducted in Manhaua which represents the “lower-class”, consisting mostly of the uneducated and first generation city-dwellers, and 9 interviews were conducted in Baixa, or the downtown, representing the educated and “upper-class”. Notes of the interview were taken and the interviews were recorded using a voice recorder. The questionnaire used during the interview is attached. Further clarification to the questions asked by the interviewer and the answers provided by the interviewee was included as needed. Open-ended requests for other information about other relevant naming practices were made by the interviewer along with accompanying clarification.

Results

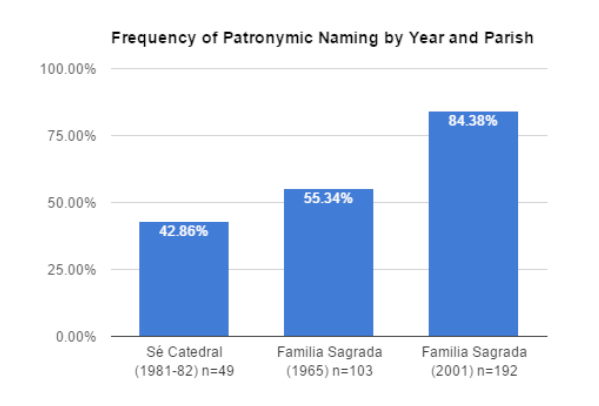

Patronymics as previously defined, are shown to be very common in Quelimane and presumably throughout Zambezia and extending into surrounding areas. This is strongly supported by both the quantitative data and the interviews. Figure 1 shows the recorded frequency of patronymic naming in the two parishes and representing three different time periods. Note that the Sé Catedral parish represents primarily Baixa and surrounding areas, which is a more urban area that is highly influenced by western culture. Also noteworthy is the 1965 set from Sagrada Família parish, which covers primarily the suburbs of Quelimane. Mozambique gained independence from Portugal in 1975, and it is not unreasonable to assume that many from that data set were ethnic Portuguese, or at any rate, highly influenced by Portuguese influence, the socalled assimilados. The most recent data set from the same parish indicate that patronymic naming is in fact the dominant naming pattern in the area.

Although the quantitative results show a strong presence of the patronymic naming pattern both historically and modernly, it is hard to draw definitive conclusions due to several factors. Firstly, the sampling doesn’t represent all of Mozambique, all of the province of Zambezia or even all of the city of Quelimane. There are three parishes in the city of Quelimane and due to time restraints, only two samples were taken from two of the parishes for a total of three samples representing three different time periods. Secondly, it was found through the interviews, talking to the parish secretary, and observed discrepancies in the records that full names of parents and other ancestors are often abbreviated or even entirely unknown to the individual. For example, a José Fernando Oliveira may say that his father’s name is Fernando Oliveira and his grandfather’s name is Oliveira. The father and grandfather very well may have another name or two at the end of their full legal name, but this is often abbreviated by the descendants. The habits of recording would depend from one secretary to the next, but the numbers found are easily enough to show the strong prevalence of some type of true patronymic naming pattern.

Scarcity of onomastic research in Mozambique leaves much unanswered. The interviews were intended to explore other aspects of anthroponyms in Mozambique and lay the foundation for future research. Onomastic practices appear to be similar to those of surrounding areas. Even patronymic naming has been recorded in Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, and historically in South Africa.

Through the interviews and the researcher’s personal experience Patronyms seem to be used mostly by the Chuabo and Lomwe ethnic groups and much less by ethnic groups further to the south such as the Sena, the Ndau, and ethnic groups occupying the southern part of the country. This is unusual in that these tribes are matrilineal. This seems to go against what is generally said about matrilineality but is observed as early as 1931 among the Bemba of then northeast Rhodesia (Richards). The co-occurance of patronyms and matrilineality could be coincidental or there could be some connection between the two.

Teknonymy is commonly practiced in Zambezia in informal situations. Parents are often referred to as pai de [child’s name], “father of…” or mãe de [child’s name], “mother of…”. This is attributed to two reasons. Firstly it is a matter of convenience. The children are the ones who most often play throughout the neighborhood and thus are generally more known. This is clearly not the only reason behind the use of teknonyms as it is common for good friends and spouses to call an individual by their teknonym. The second reason that is frequently mentioned is that of respect. Parenthood is an important rite of passage in African society and the acknowledgment of an individual’s status as a parent is seen as very important. The failure to do so seems cold or formal. Any child’s name is used in the teknonym, although the oldest child is most common, likely because it is at the birth of that child that the teknonym is established. If the name of the child is unknown by the addresser or undecided, a young mather may be called simply mãe do bebê.

Figure 1 – The prevalence of patronymic naming in two parishes representing three different years, one before national independence, two after independence. I am counting it as “patronymic” if the father’s full name enters at the end of the individuals name regardless of whether one or two names come before the father’s name. Also, it is considered patronymic if part of the father’s name enters as long as names are only cut from the end and not the middle or beginning of the sequence of names.