Jessica Evans and Dr. Wendy Baker, Linguistics and English Language

Introduction

The findings of this study have both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, this study helps in expanding our understanding of how new mediums such as texting differ from traditional forms of speech and writing (Baron, 2008). One of the important practical implications of this research is a better understanding of the appropriate uses of texting, which is important especially for non-native English speakers to understand. We hope that the findings of this study will help improve our understanding not only of how such mediums are used (especially how they relate to more traditional forms of speech and writing) but also how this information can help in improving communication via this medium.

Methodology

For two months I collected text messages from participants of different ages and genders. After collecting the text messages, I organized them to include both the age and gender of the sender and the age and gender of the recipient. I then categorized the text messages and looked for patterns in functions and politeness strategies.

In addition to the corpus analysis, I also conducted a survey using Qualtrics software. Over 300 participants, spanning fifty years in age difference, took the survey. After I collected sufficient responses, I analyzed the data, looking for patterns in age, gender, and usage.

The semi-structured interviews are still in progress. The corpus analysis and survey provide us with good, quantitative results, but the interviews will add an qualitative spin on the meaning of the results.

Results

Of 848 text messages, each message averaged at 9 words per text. However, the longest text message contained 69 words and the second longest text message contained 47 words. The shortest text messages (also more frequent) contained one character—“K”—signaling acknowledgement. These examples show that text messaging is not just for short responses, in fact, text messaging is often used for conversation, story telling, and explanations.

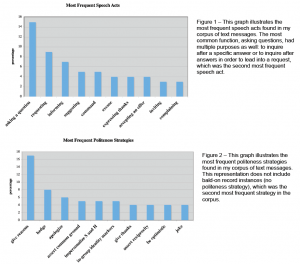

These findings coorrespond with the statistics on politeness strategies displayed in text messages. Many politeness strategies are paired, or even combined, with 2 or 3 other strategies. Curiously, I found that giving reasons, i.e. explanations or excuses, was the most common politeness strategy by a long shot.

Figure 1 shows the top 6 politeness strategies found in the corpus of text messages, represented in percentages. Only 12% of text messages contained a function without any obvious attempt at a strategy for politeness. For example, “15 min” conveys information, perhaps answering a straightforward question.

Figure 2 shows the functions of the texts and their frequencies as represented by percentages. Asking questions was by far the most frequent speech act; however, many of these questions could have been leading a request. For example, asking “Are you home?” might be a simple question but it is more likely leading to a request, such as “I mght come over if thats ok.”

Conclusion

Through our analysis of the data collected, we can conclude that politeness strategies are still a work in progress in text messaging. Though many functions, such as excuses, offers, and expressions, succeed with the aid of politeness factors, some of the most common functions, such as questions and commands, often omit such politeness strategies. There is certainly evidence showing that functions (e.g. questions) can be successful with or without politeness strategies (e.g. hedging or bald on-record). However, as this medium of communication takes on new uses (e.g. conversations), users are still in transition from concise, direct messages to longer, more polite messages.

Although we have found many results regarding how text messaging is used, it is still unclear how significant of a role gender plays in these strategies.

Limitations and Suggestions for Futher Research

As previously mentioned, determining the exact function of text messages may be difficult without the whole conversation. Rather than a corpus of individual text messages, a corpus containing full conversations would have been beneficial to the purpose of the study.We have also seen that text messaging is often used to give lengthy explanations, stories, or conversation. Many users of text messaging avoid long conversations through this medium, claiming that it would be more efficient to simply speak on the phone or in person. However, I am noticing a trend in “text message relationships,” which might be interesting to explore. Why do these conversational text message users opt for keying out lengthy conversations?