Chelsea Romney and Michael Larson, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience

Introduction

Romney, Chelsea Marital Satisfaction, Error-observation, and the Brain: Harmful or Beneficial Effects of Spouse Observation? Faculty Mentor: Larson, Michael, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience Introduction Rewarding marital relationships are associated with many positive outcomes in one’s physical and mental health (Robles, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). These benefits include improved cardiovascular functioning (Kiecolt-Glaser, & Newton, 2001), decreased depression risk (Robins & Reiger, 1991), higher self-reported levels of happiness (Proulx & Snyder-Rivas, 2013), and overall lower rates of mortality (Manzoli, Villari, Pirone & Boccia, 2007). Furthermore, positive health outcomes are not only due to marital status, but also to the quality of one’s marriage, indicated by support and satisfaction in the relationship (Holt-Lunstad, Birmingham & Jones, 2008).

In regard to performance, a large body of research exists on the effects of observation and evaluation of performance. The literature suggests that the presence of an observer will either enhance or impair performance depending on the type of individual, task, and if an observer is involved (Kim, Iwaki, Uno, & Fujita, 2005). Previous research has shown that females show heightened levels of error-related arousal compared to males when being observed during a task (Moran, Taylor, & Moser, 2012). Additionally, research on un-familiar observers shows heightened levels of anxiety and poorer performance on tests of attention, memory, and executive functions (Horwitz & McCaffrey, 2008). Interestingly, detrimental effects of an observer on cognitive functioning appear to exist even when the observer is a parent, sibling, close friend, spouse, or partner of the individual taking the test (Kehrer, Sanchez, Habif, Rosenbaum & Townes, 2000). This anxiety in relation to observation can be indicative of stress in every day interactions. Heightened arousal can have detrimental effects over time such as increased blood pressure, increased cardiovascular reactivity, and increased risk for heart disease (Eisenberger, Taylor, Gable, Hilmert, & Lieberman, 2007).

The purpose of this study was to connect these two topics in order to fill an existing gap in the research by observing the differences in error-related brain activity for spouse and unfamiliar observers. The error-related negativity (ERN) is a response-locked, negative deflecting ERP that occurs 50-100 milliseconds following an error (Falkenstein, Hohnsbein, Hoormann, & Blanke, 1991). Heightened (i.e., more negative) ERN amplitude is associated with stressful or anxiety-provoking situations (Cavanagh & Allen, 2008; Compton et al., 2007; Hajcak, Moser, & Yeung, 2005). Conversely, dampened ERN amplitude (i.e., less negative ERN) may be associated with positive emotions, such as increased life satisfaction or belief in God (Larson, Good, & Fair, 2010). Knowledge about the effects a spouse has on their partner when observing them in a task will shed light on the effects of stress in everyday life and how a spouse can influence these experiences.

Methodology

A total of 66 heterosexual married couples (132 individuals) participated in the study. All participants were 18- to 55-years old, right-handed, and native-English speakers. Subjects participated in one study session where they were given questionnaires to assess demographic information and marital satisfaction. Then, using a 128-electrode sensor electroencephalogram (EEG) net, their event-related potentials (ERPs) were measured. ERPs are changes in the brain’s electrical waveforms due to responses toward stimuli. Behavioral data was recorded during performance on a computerized reaction time task. Each participant completed one of three counterbalanced conditions: 1) observed by their spouse; 2) observed by an unfamiliar observer; 3) no observer. The observer was told to track the number of errors the participant was making.

Results

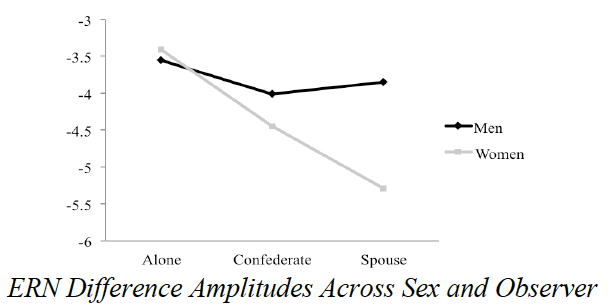

When being observed by their spouse, females experienced greater ERN amplitudes (i.e., more negative) than males F(2, 176) = 5.12, p = 0.007, η2 = 0.06. See figure below. There was increased brain activity to the spouse observer than the confederate observer.

Discussion

The difference in ERN amplitudes between males and females suggests that females experienced higher reactivity to their errors than males under observation specifically from their spouse. These results are consistent with the previous gender related findings that females have greater ERN amplitudes while being observed than males (Moran, Taylor, & Moser, 2012). These results add to the current literature by replicating these results specifically in married couples.

Possible explanations for these results may have to do with gender-related support systems. For example, current marriage literature suggests that both males and females seek females for social support. One possible interpretation of this study is that compared to females, males are showing dampened reactivity while being observed by their wives because they feel supported by her as a female, rather than just as a spouse (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001).

An additional explanation may have to do with the connection between ERN and anxiety. Previous research shows a relationship between negative ERN amplitude and anxiety (Moser, et. al, 2013). So these results may have implications for spousal interactions and the role anxiety plays, especially for the female spouse.

References

- Cavanagh, J. F., & Allen, J. J. (2008). Multiple aspects of the stress response under social evaluative threat: An electrophysiological investigation. Psychoneuroendocrinology , 33 (1), 41–53. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.007

- Compton, R. J., Carp, J., Chaddock, L., Fineman, S. L., Quandt, L. C., & Ratliff, J. B. (2007). Anxiety and error monitoring: increased error sensitivity or altered expectations? Brain and Cognition , 64 (3), 247–256. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2007.03.006

- Eisenberger NI, Taylor SE, Gable SL, Hilmert CJ, Lieberman MD. Neural pathways link social support to attenuated neuroendocrine stress responses. NeuroImage. 2007;35:1601-1612.

- Hajcak, G., Moser, J. S., & Yeung, N. (2005). On the ERN and the significance of errors. Psychophysiology , 42 (2), 151–160.

- Holt-Lustad J, Birmingham W, & Jones BQ (2008). Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship qulaity, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. ;35:239-244.

- Horwitz JE, McCaffrey RJ. Effects of a third party observer and anxiety on tests of executive function. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2008;23:409-417.

- Kehrer CA, Sanchez PN, Habif UJ, Rosenbaum GJ, Townes BD. Effects of a significant-other observer on neuropsychological test performance. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2000;14:67-71.

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK & Newton TL (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 127:472-503.

- Kim EY, Iwaki N, Uno H, Fujita T. Error-related negativity in children: Effect of an observer. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2005;28:871-883.

- Falkenstein, M., Hohnsbein, J., Hoormann, J., & Blanke, L. (1991). Effects of crossmodal divided attention on late ERP components. II. Error processing in choice reaction tasks. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology , 78 (6), 447–455.

- Larson, M. J., Good, D. A., & Fair, J. E. (2010). The relationship between performance monitoring, satisfaction with life, and positive personality traits. Biological Psychology , 83 (3), 222-228. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.01.003

- Manzoli L, Villari P, Pirone G, Boccia A. Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:77-94.

- Moran, T. P., Taylor, D., & Moser, J. S. (2012). Sex moderates the relationship between worry and performance monitoring brain activity in undergraduates. International Journal Of Psychophysiology , 85 (2), 188-194. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.05.005

- Moser, J. S., Moran, T. P., Schroder, H. S., Donnellan, M. B., & Yeung, N. (2013). On the relationship between anxiety and error monitoring: A meta-analysis and conceptual framework. Frontiers In Human Neuroscience, 7

- Proulx, C. M., & Snyder-Rivas, L. A. (2013). The longitudinal associations between marital happiness, problems, and self-rated health. Journal Of Family Psychology, 27 (2), 194-202. doi:10.1037/a0031877

- Robins L, & Reiger D. (1991). Psychiatric Disorders in America . New York, NY: Free Press.

- Robles TF, & Kiecolt-Glaser JK. (2003). The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiology & Behavior. 79:409-416.