Kayla Alder and Dr. Brock Kirwan, Psychology

Introduction

Previous research suggests that those with depression have altered brain structures compared to control participants. For example, depressed individuals have smaller hippocampal volumes than those not diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Brown, Rush & McEwen, 1999). The hippocampus plays a major role in memory, especially by storing different stimuli as separate and distinct memories in the brain (Yassa & Stark, 2011). This process of storing the stimuli separately correctly is known as pattern separation (PS). Depressed individuals also have reduced neurogenesis (the birth and growth of new neurons in adulthood) in the hippocampus compared to controls. Those diagnosed with depression, then, struggle to separate stimuli into distinct memories due to both reduced hippocampus size and reduced neurogenesis.

Methodology

We conducted a study in which we examined the memory of a depressed population through tasks that tax pattern separation ability, similar to those used previously in Shelton and Kirwan’s research (2013). In their study, Shelton and Kirwan tested participants from a population of undergraduate students with a range of depression symptoms, but none who had a diagnosis of MDD. The participants completed questionnaires on exercise, anti-depressant use, and a questionnaire to evaluate depression symptoms. Participants also completed a pattern separation task in which they were shown several blocks of photographs on a computer, one at a time. Each participant viewed a picture that was either shown only once (first), more than once (repeat), or that had a similar, but not the identical, picture pair (lure). The participants were asked to identify each photograph as new, old, or similar. They viewed 107 pictures in each block and a total of six blocks.

Our study, unlike the one previously described, only included those diagnosed with MDD and a control group. We performed MRI scans on each participant in order to relate the behavioral performance to the brain changes in depression. The clinically depressed patients were recruited through the Counseling Center at Brigham Young University (19 participants). The control group was contacted through Brigham Young University (17 participants). All participants were given a Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) and the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) administered by a PhD student in clinical psychology in order to determine the severity of depression of the depressed participants and to ensure those with depression meet the criteria for MDD. Participants were also given the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) and the Test of Premorbid Functioning (TOPF) in order to control for other possible differences between groups.

In the behavioral procedure, all participants completed the pattern separation task that was employed by Shelton and Kirwan in their study. However, in this study, the participants had a 2.5 second duration for each photograph (whereas in the previous study the test was self-paced). It was expected that those participants diagnosed with MDD would more often identify similar items as old, thus suggesting they fail to pattern separate. We expected that they would instead participate in pattern completion due to reduced size of the hippocampus and lack of neurogenesis.

Results

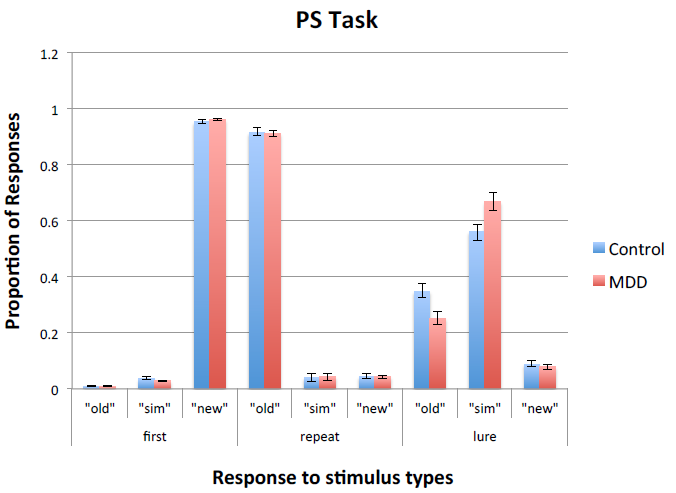

After both groups (control, MDD) performed the memory task, independent sample t-tests were performed. As expected for our control measures, the two groups did not differ on either the RAVLT (F=2.290, p=0.139) or the TOPF (F=0.411, p=0.526). BDI scores between groups were significantly different from one another (F=4.187, p=0.049), confirming the efficacy of the test for our sample. Pattern separation (PS) scores between the two groups were not significantly different (F=0.094, p=0.762). An ANOVA showed that group had a main effect on lures called “old” (F(1,35)=5.438, p=0.26) and lures called “similar” (F(1,35)=8.393, p=0.006) (see Figure 1). A regression showed that PS scores and BDI scores was not significantly correlated (Pearson = 0.094, p= 0.581).

Figure 1: Responses to memory task for controls and MDD

MDD are more likely to correctly identify lures as “similar” and controls were significantly more likely to identify lures as “old.” There are three different stimulus types: first, repeat, and lure. Participants may respond to stimulus types as either “old,” “similar,” or “new” (see Methodology). Each stimulus type is listed with the three possible responses and the listed proportion of those responses to the stimulus.

Discussion

As displayed in results, contrary to our hypothesis, clinically depressed women do not have lower PS scores than controls nor are they more likely to incorrectly identify similar items as “old”. Instead clinically depressed participants were significantly more likely to correctly identify similar items as “similar” and controls were significantly more likely to identify similar items as “old”. Unlike Shelton and Kirwan findings, the regression to predict pattern separation scores from BDI scores was not significant in this study.

Conclusion

There are several factors that may have led to the results found in this study. First, the majority of MDD participants were first episode (n = 14). Perhaps performing this study with an MDD group of which more participants have had several episodes of depression (and potentially more damage to the hippocampus) would lead to the results expected. Further, MDD participants may have performed better than we hypothesized due to increased motivation to perform well on the task. Because the study was designed to eventually help those with MDD, these MDD participants may have been trying harder on the test. Lastly, BDI may not be a sensitive enough measure of depression. We propose that future studies continue to explore the effects of depression on memory specificity with a more severely depressed population and with a variety of depression measures.

References

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory (2nd ed.). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

- Brown, E. S., Rush, A. J., & McEwen, B. S. (1999). Hippocampal remodeling and damage by corticosteroids: Implictions for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 21(4), 474-484.

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., … Dunbar, G. C. (1998). the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 22-33.

- Shelton, D. J., & Kirwan, C. B. (2013). A possible negative influence of depression on the ability to overcome memory interference. Behav Brain Res, 256, 20-26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.08.016

- Yassa, M. A., & Stark, C. E. (2011). Pattern separation in the hippocampus. Trends Neurosci, 34(10), 515-525. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.006