Brandon Clifford and Larry Nelson, School of Family Life

Introduction

Social withdrawal functions as an umbrella term capturing various types of withdrawn behavior in children (Coplan & Rubin, 2010). Past research has defined more specific types of withdrawal using various approaches including observed play behaviors (Coplan, et al., 1994). To illustrate, reticent children (a form of withdrawal) primarily engage in onlooking and unoccupied behavior while solitary-passive children engage in solitary constructive and exploratory behavior. Although this deductive step furthers the social withdrawal research in describing the characteristics and behaviors of children, the language skills of these distinct groups requires further investigation.

Withdrawal and language contribute to a child’s overall social development. For example, a social child possessing adequate language skills will more likely flourish in social situations with others. In contrast, a child struggling with withdrawal or language skills is more likely to struggle in social situations. Past research supports these assessments. For example, withdrawal has been linked to internalizing behaviors and negative peer relationships (Bowker & Raja, 2011; Coplan et al., 2008; Nelson, L., Rubin, K., & Fox, N., 2005). Further, children with fewer developed language skills have been found to have a more negative social status (Naerland, 2011). Additionally, withdrawal has been found to be linked to lower levels of language development in the form of pragmatic skills (Coplan & Weeks, 2009), phonological awareness (Spere et al., 2004), mean-length-of-utterance (Evans, 1987) and vocabulary development (Lloyd & Howe, 2003). Despite the work that has examined links between social withdrawal and aspects of language, the work is yet to examine whether specific types of withdrawal differ from one another in their language abilities. Language is a generally overt behavior of children and understanding the language differences among children with various forms of withdrawal will help researchers and practitioners understand and help withdrawn children in overcoming or coping in social situations.

Thus, utilizing play behaviors as indicators of subtypes of withdrawal (reticent, solitary-passive), the main purpose of the current study is to discover language development differences among children with various forms of withdrawal. Our hypotheses are as follows: 1) children in each withdrawn subtype will have lower levels of language performance in comparison to the social group as they are less likely to interact with peers and 2) the reticent-withdrawn group will have lower levels of language performance compared to the solitary-passive group as they are more inhibited by their anxiety to enter any play situation with others present.

Method

The pilot sample contained 42 children both males and females all enrolled students at the Brigham Young University (BYU) Child Laboratory. Data collection occurred during two visits to the Child Lab.Four same-sex unfamiliar peers were observed in a laboratory setting while engaged in unstructured, free play. Their behaviors were recorded and then coded using the Play Observation Scale (POS). The first withdrawn variable of interest in the study was reticence which comprised onlooking (watching others play without joining in) and unoccupied (wandering aimlessly, doing nothing) behaviors. The second withdrawn variable was solitary-passive withdrawal which included solitary constructive (e.g. building), exploratory (e.g. examining objects) and occupied behavior. During these freeplay sessions, children’s utterances were recorded and subsequently transcribed to assess three main aspects of language development including: 1) Mean-Length-of-Utterance (MLU; total morphemes divided by total utterances), a measure of syntactic development, 2) Type-Token Ratio (TTR; unique words divided by total number of words), a measure of linguistic diversity and 3) Category Range (CR; a checklist of items of language understanding), to measure language knowledge.

Results

To create comparison groups for the ANOVA analysis, the following criteria was used. Children who placed in the top quartile of exclusively one type of withdrawal were placed in the reticent or solitary-passive group. To create a control group, children who did not place in the top quartile of either type of withdrawal or placed in the top quartile of both types of withdrawal were placed in the social group. This criteria yielded 12 children in the reticent group, 5 in the solitary-passive group and 25 in the social group. These three groups were used as the independent variable or factor in the analysis.

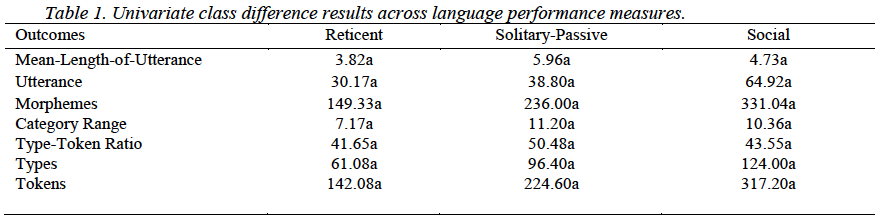

ANOVA analysis was utilized to measure how children with different sub-types of withdrawal compared in their language performance, which was used as the set of dependent variables. ANOVA results indicated no significant differences between the three groups (reticent, solitary-passive, social) and their language performance scores, Wilks Λ= .621, F(14,66) = 1.27, p < .25. The multivariate η2 based on Wilks’s Λ was .21. Table 1 contains the means and standard deviations of the dependent variables for the three groups.

Discussion

According to the ANOVA analysis used, neither of our hypotheses were supported. Reticent and solitary-passive children did not differ in their levels of language development. Further, neither reticent nor solitary-passive children differed from social children in their language development. Notwithstanding, preliminary correlational analyses suggested a link between language development and some withdrawn behaviors. Moreover, numerous previous studies have found links between withdrawal and language development (e.g. Coplan & Weeks, 2009). Despite the research supporting the existence of this link, the current study found no difference between various withdrawal groups.

Limitations for this study suggest a need for future research. The current study’s sample size is limited in its generalizability, especially as the sample (n = 42) was separated into smaller groups. Despite the fact that our ANOVA analysis yielded non-significant mean differences among groups, the mean difference appear to be sizable. A larger sample would increase the power of analyses and thereby increase the possibility of detecting differences should there be any. Future research should work to confirm both whether children with various types of withdrawal differ in their language abilities and how their language abilities are affected by social withdrawal.