Zach White and Philip Rash, Ph.D., Counseling and Career Center & Undergraduate Education

Introduction

Peer education is well established as an effective means of supporting first-year students in their transition to the university experience (Shook & Keup, 2012) (Esplin, Seabold, & Pinegar 2012). In large part, the success of peer education programs depends on the selection of peer educators, but very little research has been conducted to investigate how specific pre-requisites correlate to peer educator success. This project seeks to understand the correlation between the five pre-requisites for peer educator selection identified by Terrion and Leonard (2007) and peer educator success within the First-year mentoring program at Brigham Young University.

Methodology

Participants were comprised of 55 peer educators (PEs) (35 female), selected from the body of new peer mentor hires in the office of BYU First-year Mentoring. The majority of the participants identified as white (49), two as Latino, two as Asian/Pacific Islander, and two as African-American. This represents a greater degree of diversity than is present among the general student population. The mean age of participants was 20.58 (standard deviation = 1.61). All were enrolled as full-time students.

Data for the study came from (a) participants’ PE job applications and interview and (b) performance data collected during participants’ first semester as peer educators. One objective of the study was to evaluate the statistical correlation between the five pre-requisites for peer educator applicants identified in Terrion and Leonard and the PE’s success in their first semester of employment. Consequently, relevant data from PE applications were collected and served as independent variables in a multiple regression analysis. The dependent variable for the study was a composite measure of PE success that aggregated participants’ frequency of meetings with assigned first-year students, ratings from supervisors, and measures of the relational strength between participants and the first-year students they were assigned to support. Variables from the job application include but are not limited to strength of recommendation and scores from essays about significant learning experiences and the applicant’s transition to college. Variables from the interview include scores from interview questions and levels from professionalism.

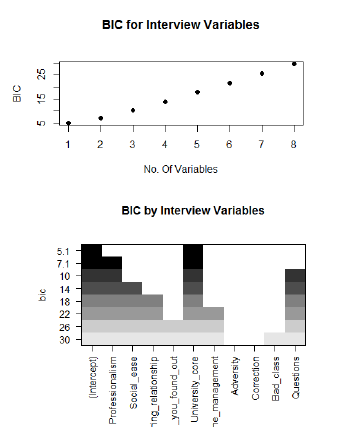

Since we were considered with both inference on the significance of each pre-requisite and the prediction of success in certain key areas based on characteristics shown in interview and application settings, we proposed best subset variable selection methods based on Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). We decided to use BIC because it is known to be informative in both inference and prediction applications since it imposes a penalty on including too many variables in the model. After we used this variable selection method, we fit the proposed linear model, along with some other models based on theory. We then analyzed the significance of the models and the individual models. Since “success” can be difficult to characterize and quantify in peer educator settings, we used similar methods for the different components of the composite measure of PE success: number of meetings, ratings from supervisors, and measures of relational strength with participating students.

Results

Initial results of this analysis suggested that, of the five pre-requisites proposed in Terrion and Leonard’s taxonomy, only university experience (p < .01) significantly influenced PE success during the first semester in their role. Gender, Race, average number of hours worked per week, GPA, and prior experience with mentoring did not have a statistically significant influence upon PE success. Additional analysis demonstrated that, when controlling for age, university experience did not significantly influence PE success during the first semester of their service. Rather, university experience seemed to be a proxy measure of the significant influence of age upon PE success.

Initial results of this analysis suggested that, of the five pre-requisites proposed in Terrion and Leonard’s taxonomy, only university experience (p < .01) significantly influenced PE success during the first semester in their role. Gender, Race, average number of hours worked per week, GPA, and prior experience with mentoring did not have a statistically significant influence upon PE success. Additional analysis demonstrated that, when controlling for age, university experience did not significantly influence PE success during the first semester of their service. Rather, university experience seemed to be a proxy measure of the significant influence of age upon PE success.

As we conducted this analysis, we found that the number of variables that minimzed BIC for both application and interview variables was one, which is to be expected. Thus we consider the costs of including more variables by comparing the respective BIC values. The plots show steps in this process for the interview variables. For example, since the BIC of the models with one, two, and three variables are similar, we can reasonably use any of them. When we go through this process and fit reasonable models, we didn’t find any significant variables in the pre-requisites.

Discussion

Through a comprehensive literature review, Terrion and Leonard proposed fifteen characteristics associated with successful peer education. They separated these characteristics into three groups. Group one consisted of pre-requisite characteristics (i.e. accessibility to students, gender and race, university, academic achievement, and prior mentoring experience). Group two consisted of two separate types of skills and attributes that are important in mentoring, which were distinguished by Kram and Isabella’s two classes: psychosocial (i.e. communication skills, independent attitude to mentoring, mentee, and program staff) and career-related (i.e. self-enhancement motivation or orientation or program of study) (1985). Although several researchers have studied how certain attributes can contribute to either psychosocial or career-related functions (Terrion and Leonard 2007), minimal research has been done to analyze the correlation between the Terrion and Leonard’s pre-requisites and peer mentor success. The current project could initiate a more empirically oriented discussion of significant pre-requisites and characteristics that should be consider by program administrators in the peer mentor selection process.

Conclusion

The fact that no pre-requisites from the interview and application process were found to be significant or predictive of success may be indicative that certain procedures in the hiring process may not be particularly effective. As we collect more data about the hiring process, we will continue to analyze the results. However, we will also assess other ways to analyze this data because multiple regression may not be the most effect methodology.

Scholarly Sources

Kram, K. & Isabella, L. (1985) Mentoring alternatives: the role of peer relationships in career development, Academy of Management Journal, 28, 110–132.

Terrion, J.L. & Leonard, D. (2007). A taxonomy of the characteristics of student peer mentors in higher education: Findings from a literature review. Mentoring & Tutoring, 15(2), 149-164.

Shook, J. L., & Keup, J. R. (2012). The benefits of peer leader programs: An overview from the literature. In J. R. Keup (Ed.), New directions for higher education: Peer Leadership in higher education (5 – 16).

Esplin, P., Seabold, J., & Pinnegar, F. (2012). The architecture of a high-impact and sustainable peer leader program: A blueprint for success. In J. Keup (Ed.), New directions for higher education: Peer Leadership in higher education (85-100).