Jeremy Ingersoll and Gerrit van Dyk, Religion

In the early ‘90s, ninety-four Hispanic members of the LDS church were interviewed by the BYU Redd Center for Western Studies and provided oral histories. All interviewees were from a Spanish-speaking country or were the children of parents who came to the United States from a Spanish-speaking country, and all but a few were living in Utah or California. This gave us the opportunity to look into the past of Hispanic Latter-day Saints in Utah, and compare it to those living in a different environment in California. We looked at these oral histories with the hope to determine to what degree Hispanic Latter-day Saints in Utah retain the cultures of their homeland. Looking at interviewees in California gives us the opportunity to see the results in a state with a much higher concentration of Hispanic Americans. Our main question was “How well do Spanish-speaking congregations in the LDS church assist them in retaining their culture?

The National Center for Cultural Competence defines culture as an “integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts, communications, languages, practices, beliefs, values, customs, courtesies, rituals, manners of interacting and roles, relationships and expected behaviors of a racial, ethnic, religious or social group; and the ability to transmit the above to succeeding generations”.1 This is quite a broad, nonetheless complete definition, but we chose to focus on the most visible characteristics of what composes a culture, namely that which is included in the oral histories: language and holiday observance, to determine to what extent each individual was actively preserving his or her culture.

We looked at these cultural retention factors within the scope of religion, specifically the LDS church; in order to see what roles religion plays in the cultural retention and decay of Hispanic immigrants in the U.S. According to Mark Mullins a professor of Asian cultures in New Zealand, [churches] play: “conservative roles” in maintaining ethnic customs, language, and group solidarity, or they play “adaptive roles,” accompanying and accommodating ethnic populations in the arduous acculturation process toward the gradual loss of many ethnic markers.2 These are not mutually exclusive orientations. Based on language retention and cultural holiday celebration, we sought to find out where the LDS church falls on the spectrum between playing a “conservative role” and an “adaptive role”, since the two are not mutually exclusive.

An important component of this project on which more research needs to be done is the nationality demographic of Spanish-speaking congregations and the wide range of cultures that reside therein. The data we used contained people from twelve different countries, with Mexico and Peru being the most represented. These differences complicate their cultural retention.

Ebaugh and Chafetz from the University of Houston are two scholars who have done extensive work on immigrants and religious culture. In their article titled: Structural adaptations in immigrant congregations, “religion provides cultural capital for the reproduction and passing on of ethnic identity through its use of language…”3

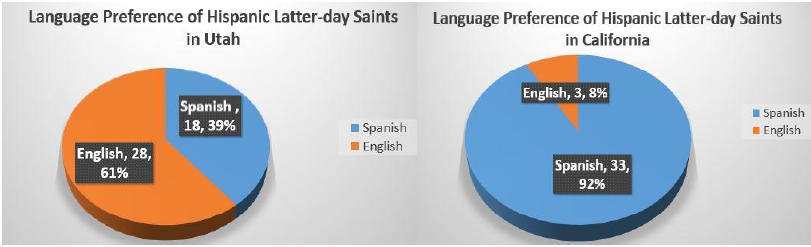

The graphs indicate the greater amount of Spanish preferred LDS in California.

Hispanic Latter-day Saints living in the United States identify with each other through their common language of Spanish. The Mormon Church provides them with the opportunity to worship in an environment that preserves this aspect of their ethnic identity.

Looking back at Mark Mullins’ definition of culture as an “Integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts, communications, languages, practices, etc. Many of the oral history interviews included a question about whether or not the interviewee still celebrated holidays from their native country, so this can tell us a lot about their level of cultural retention.

The numbers taken from the oral histories indicate that Hispanic LDS members in California celebrate holidays from their native countries more often than Hispanic members living in Utah.

We analyzed these factors taking the numbers from the oral histories that indicated them. We also provided supporting quotes taken directly from the oral histories that gave examples of their preferences and their points of view in terms of language preference and holiday observance as Hispanic Mormons living in the United States.

While the church succeeds at accommodating to the language needs of its members, the numbers suggest that at least in Utah, LDS Hispanics are more likely to assimilate to American culture than to preserve the culture of their native country.

Based on what we have seen, does the LDS church fall more on the adaptive or the conservative side of the spectrum? Hispanic members of the LDS church in California are able to preserve their culture more consistently, but it is likely due to their communities and surroundings rather than their membership in the Church.

We presented our research in a session of the Utah State Historical Society Conference.

References

- Peterson, Elizabeth and Coltrane, Bronwyn. Culture in Second Language Teaching. Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Mullins, Mark. 1987. The life-cycle of ethnic churches in sociological perspective. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 14(4):321-34.

- Ebaugh, H.R. and J.S. Chafetz. (2000). Structural adaptations in immigrant congregations. Sociology of Religion, 61, 135-153.