Katherine Westmoreland and Christopher Karpowitz, Political Science

Background

In the 2014 presidential election, only 36% of eligible voters cast a ballot on Election Day. Voter turnout is especially low in non-presidential elections and the already bleak number of voters is heightened when examining young voters, withonly 21.3% of 18-19 year-olds voting in 2014.

Political science research has long shown that people are less likely to vote when there are significant requirements of time, information, or money involved in the voting process. These different challenges are often categorized as the “costs of voting.” The difference between young voter turnout and turnout among those of an older generation may indicate that there different types of voting costs. This research project aims to differentiate the costs of voting into a) one-time and b) recurring costs. When the costs of voting are better understood, this information can be used to reduce the challenges of voting for first-time voters to increase voter turnout among this bloc.

I predict that one-time costs of learning the electoral process (like how to vote, where to register, etc.) are far greater than recurring costs (of time, information gathering, etc. , which in part describes the low voter turnout among young Americans. ’

Research Questions

- Do first-time voters have larger obstacles to overcome when casting a ballot?

- Will reducing informational costs of voting increase voter turnout?

Methodology

In October 2014, I sent an email to select introductory-level classes of BYU students (American Heritage and Political Science 110), inviting them to participate in study. Those who signed up for the study were block randomized on whether or not they were registered to vote at the time of sign-up, then randomly assigned to receive the treatment or control. Those in the control group were contacted in mid-November and asked to reported whether or not they had voted.

Those in the treatment group were emailed a brief survey in late October, containing nonpartisan information on their home state’s congressional candidates (recurring costs). This treatment group was then contacted in mid-November, like the control group, to report voter turnout. Another treatment existed to test one-time voter costs, through emailing unregister respondents information on how to vote, though a survey programming error exempted this treatment. As a result, I was only able to examine Research Question 2.

Findings

Respondents rank being out of town, not knowing candidates, and being busy as their largest barriers to voting.

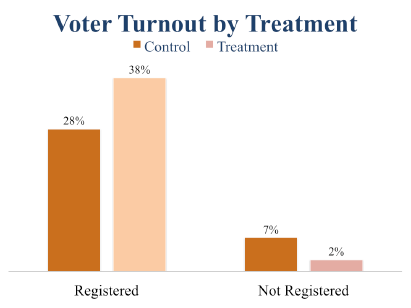

As a result of my experiment, I found that registered voters who received information about their candidates (treatment) were 10% points more likely to vote than other registered voters who did not receive similar information (control). Alternatively, nonregistered students who received information about their candidates were 5% points less likely to vote than non-registered students receiving no information. Similarly, non-registered students who received the treatment were less likely to register to vote on their own accord, with 18% of the control group registering to vote and only 9% registering to vote by the time of the Post-Election Survey.

I also found that registered voters who received the treatment were significantly less likely to cite not knowing candidates as a barrier to voting, meaning the treatment helped respondents learn about candidates. All these findings hold even when controlling for other common predictors of turnout, like income and race.

Figure 1 – The Calculus of Voting essentially states that people will vote when their civic duty outweighs the costs of voting.

Figure 2 – Figure 2 shows the voter turnout levels of registered voters and non-registered voters (at the time of signup), by treatment levels. Differences between the control and treatment groups are significant at the .09 and .11 levels for registered and non-registered respondents, respectively.