Courtney Petersen and Dr. Charles W. Nuckolls

Main Text

The city of Visakhapatnam hugs the shoreline of the Bay of Bengal on the East coast of Andhra Pradesh, India. Once a small collection of fishing villages, this city is now a bustling metropolis housing businesses, universities, travelers, students, and families from both metropolitan and rural backgrounds. As with most growing cities in India, Visakhapatnam is bombarded with outside influences from the western world in the form of media, global businesses, and travel as it develops as a city. This advancement in technology and interaction with global society benefits the people in Visakhapatnam by introducing them to opportunities that will allow them to grow financially and socially. Though globalization introduces these benefits it also thrusts an individual into an environment where she must continually negotiate between her traditional past and her modern future.

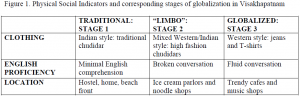

During the five months I lived and conducted ethnographic research in Visakhapatnam, locally known as Vizag, I discovered that it is in a limbo stage of globalized development. Aspects of the traditional Indian value-system such as respect for the family, the obedient role of a woman, and the importance of an arranged marriage are still highly important in the society, but as Vizag connects with the globalized world, western ideals of individualism and independence, which conflict with traditional Indian values, flood the scene and force the individual to live in a valueconflicting present (Lieber and Weisburg 2002:276). A demographic that is highly affected by globalization in specifically Visakhapatnam is university-age women. As these women are exposed to new concepts and ideas about how they should live their life they must reevaluate their own value-system and reconstruct their own identity accordingly. For many women this change in value-system is physically manifested in the clothing they chose to wear, their proficiency in English, and where they spend their time in the city. From these physical social indicators one can make assumptions about how a certain individual feels about her role as a young adult in an increasingly globalized Indian city (See Figure 1).

My original study centered on globalization and female identity, but once in India I realized that my research needed to have a narrower focus. Of all the aspects of Indian society affected by globalization in Visakhapatnam, I found that changing views on marriage are the most relevant to young women and their families. My final research focuses on the interplay between globalization, marriage practices, and identity.

Traditionally, Indian women allow their parents to arrange their own marriage, but now the concept of a love marriage where the woman chooses her own spouse is becoming more popular. These two marriage options directly conflict and in many cases result in secret romances where the parents are completely unaware of their child’s activities and marriage intentions. This results in a division between young women and their parents that only increases in size as society itself becomes more globalized.

Through extensive participant observation and one-on-one interviews, I gathered specific accounts of this division. As recounted by the university-age women I interviewed, the parents of some informants accepted their daughter’s alternative view of relationships and marriage while others forcefully disagreed and restrained their daughter from such relationships. This difference of opinion on marriage results in a stressful power struggle between parent and daughter. Specifically, the struggle these women face lies in balancing what is expected socially and culturally by the parents and what is desired socially and culturally by the young woman.

One informant in particular negotiated this power struggle by tricking her parents into thinking that she did not know the man they arranged for her to marry. In reality, it was actually her secret boyfriend. Two informants, Amrita and Neha, approached this struggle in a different way. Both found that increasing communication with their parents helped relieve some of the tension. Amrita called this open dialogue a means to “bridge the gap” between the individual and her parents.

The globalization of Visakhapatnam is causing a drastic shift in how university-age women understand and relate to current marriage practices and the power relationships associated with them. After considering the cultural data I collected and specifically the examples of Amrita and Neha, I conclude that the tensions resulting from this change can be overcome through a revived importance placed on communication between the young woman and her parents. In this way both parties are actively engaging in a solution that will “bridge the gap” created by globalization between young women and their parents in Visakhapatnam.

Publication and Presentation

• Displayed research poster at the Mary Lou Fulton Mentored Student Research

Conference in April 2010.

• Submitting full research article to BYU Kennedy Center Inquiry Journal for possible

publication in 2011.