Ian Hansen and Dr. Darren Hawkins, Political Science

Using survey data from across Latin America, I sought to determine whether compulsory voting laws have negative effects on constituents’ views toward democracy. I expected to find that such laws influence voters to have lower appraisals of democracy in their country.

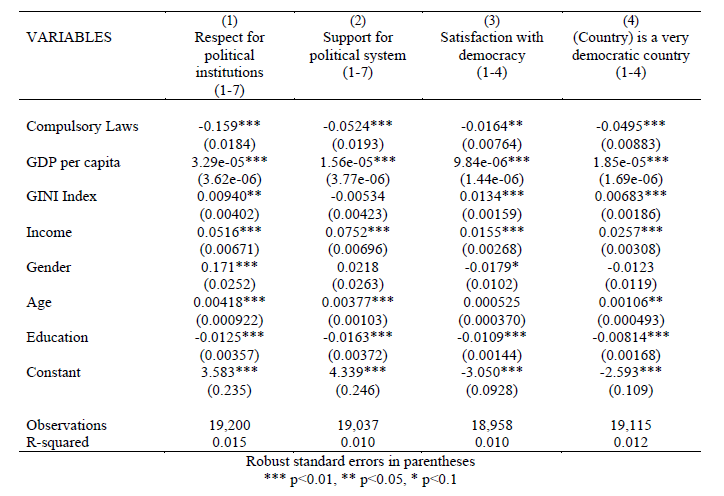

The analysis yielded results that lend significant support to my theory. Controlling for individual demographic variables and the country-level indicators of GDP per capita and GINI Index (which measures economic inequality), it appears that compulsory voting laws do, in fact, have a statistically significant effect on support for and satisfaction with democracy. Further, although the substantive effects are small, the effects appear to be in the direction I expected. The table below presents the regression results:

For each of the dependent variables, it appears that as the strictness of compulsory voting laws increases, appraisals of democracy and the political system in general do in fact worsen, though the size of these effects are small. These results suggest that compulsory voting laws may weaken support for democracy and that this effect intensifies somewhat as the punitive force attached to noncompliance is increased. Moreover, none of the results seem to lend credence to any of Engelen’s contentions. Most notably, Engelen argues that the very act of a government enforcing a mandatory voting law sends an important message to the public that the government values the voice of each of its constituents; he contends that this message is powerful enough to improve citizens’ perceptions of how democratic their country truly is (Engelen 38-9). However, my findings with regards to the fourth dependent variable, in which respondents express how democratic they believe their country is, undermine this claim. My findings indicate that as compulsory voting laws become stricter, respondents view their countries as less democratic; while the substantive effect is small, the finding is highly statistically significant.

In considering this analysis, a few limitations bear mentioning. First, the manner in which I coded countries according to the strictness of their compulsory voting laws is imperfect. I chose to separate these groups out considering two factors: (1) existence of compulsory voting laws, and (2) the number of penalties attached to noncompliance. While I stand by this choice given the data available to me, it is true that this 0-2 scale is not a perfectly continuous variable, though I treat it as such in my analysis. I would argue, however, that the scale is at least roughly continuous, because the scale increases as the strength of compulsory voting laws increases. A second important limitation becomes clear when the R-squared statistics for each of the regression is considered. For each regression, the R-squared is low. This suggests that there are significant factors that affect my dependent variables that I did not include in my analysis. This finding is unsurprising; however, coming up with a comprehensive list of all of the variables, both at individual and country-wide levels, that may affect these dependent variables is a daunting task, one that time did not allow for. I simply did my best to control for basic demographic and economic indicators.

The low R-squared for the regressions may open a door for further research. Given that there seem to be several factors that go unaccounted for here, what else may be predictive of support for and satisfaction with democracy? Further, which among these factors have the largest predictive power in this regard? I submit that partisan gridlock in lawmaking bodies may be one of these factors. As gridlock increases, policy change becomes increasingly difficult, which in turn may lead to increased dissatisfaction with democracy and democratic outcomes among constituents.