Thomas Kelemen and Dr. Michael Ransom, Economics

Over the past twenty years, the Denver Regional Transit District has developed an extensive light rail public transit system in the Denver, Colorado metro area. This development was motivated, at least in part, by severe highway congestion on important highway routes to downtown Denver. In a recent analysis, Bhattacharjee and Goetz (2012) suggest that the presence of the light rail system has reduced the growth of highway traffic on major highways near the light rail network by ten percent, relative to routes in areas not served by light rail. We show that such an effect is implausibly large. We provide evidence that growth in highway usage in the study area was constrained by the capacity of highways, and that initiation of light rail service had no discernible effect on the use of congested highways near light rail lines. We also document that the fraction of commuters who use public transit has continued its long-term decline during the period of the study, most likely due to the continued suburbanization of population and employment in the Denver metro area, which we also document.

In their analysis of traffic on highways in the Denver area, Bhattacharjee and Goetz 2012) claim that the availability of light rail transit in Denver reduced the growth of traffic on major highways that were close to light rail relative to major highways that were not close to light rail lines over the period from 1992 through 2008. In fact, traffic did grow more rapidly in areas far from light rail service. The mistake of Bhattarcharjee and Goetz is to interpret this difference as causal. Highways near light rail lines are very different than those far away. In particular, highways near light rail lines had higher levels of congestion than those further away—light rail lines were built near these highways because the highways suffered from severe levels of congestion.

We provide evidence that congestion on I-25, I-225 and Santa Fe Drive was consistently severe over the period during which the light rail network was constructed. Growth of highway traffic was constrained primarily by the level of congestion—highways were already operating at capacity during hours when commuters wanted to use them. When new capacity was added to these highways, it was quickly filled by additional commuters. On the other hand, we can find no evidence to suggest that initiating light rail service reduced highway traffic.

We also document that population and employment in those areas served by light rail has grown much more slowly than in outlying areas of the Denver metropolitan area. It is reasonable to expect traffic to grow more rapidly in outlying areas, as well.

Denver’s light rail network provides a high level of service to its users. However, the number of rail users is very small compared to the number of highway users. Light rail does not provide noticeable benefits to highway users. In particular, light rail has not reduced highway congestion in the Denver area. Building light rail to reduce highway congestion in cities like Denver is something like taking antibiotics to cure influenza–we want to do something to “make it better,” but the cure is ineffective. Downs (2004) discusses a number of ways to mitigate congestion. The most promising methods involve charging tolls for access to congested highways. Hall (2013) shows that tolling just some of the lanes of a highway can yield large benefits to commuters.

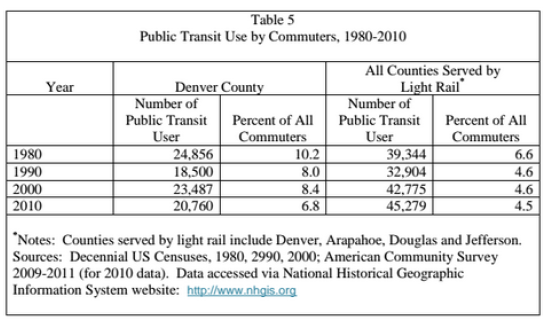

The above chart documents the use the public transit in Denver. Despite the continued construction of the light rail in Denver the total number of commuters by public transit has decreased from 2000 to 2010. In addition, the percent of total commuters has also decreased.