Rachel Maxwell and Dr. Jeffrey Reber, Psychology

Introduction

Priming is a method often used in psychology research to activate implicit attitudes and behaviors. Priming has been effectively demonstrated in advertising and the marketplace (North, Hargreaves, & McKendrick, 1999; Milliman, 1982; Jacob, Gueguen, & Boulbry, 2011), politics (Berger, Meredith, & Wheeler 2008; Rutchick, 2010), business (Kay, Wheeler, Bargh, & Ross, 2004), social norms (Aarts & Dijksterhuis, 2003), studies of aggression (Berkowitz & LePage, 1967), and studies of racism (Wittenbrink, Judd, & Park, 2001). In these studies certain cues in the environment led to an unconscious activation of an attitude or behavior.

While previous research has investigated how religious environmental affects explicit beliefs and attitudes, we seek to compare the effects of religious environmental priming and scientific environmental priming on participants’ implicit attitudes about faith and science (Labouff et al., 2012). Specifically, we hypothesized that participants in the religion primed environment would manifest a higher implicit preference for faith over science than participants who completed the IAT in the science primed environment. Given the findings of previous research (Reber, Slife, & Downs, 2012) we expected no difference in explicit attitudes.

Procedures

Undergraduate university students were recruited using Brigham Young University’s SONA psychology research participation system. Participants were randomly assigned to participate in either a classroom in the Joseph Smith Religion Building or the Eyring Science Center on BYU campus. Each location was primed by placing either religious or scientific objects, drawings, and signs in visible but inconspicuous places throughout the room, as if they were always there or had been left by a previous class. Research assistants wore white lab coats in the science condition and church attire such as a white shirt and tie (men) or a dress/skirt (women) in the religion condition. The scripts research assistants read aloud to the participants also included relevant religious or scientific terms as subtle primes. Post-participation interviews revealed that very few participants were consciously aware of the environmental primes.

Participants took an Implicit Association Test that measures implicit attitudes towards faith and science (Reber, Slife, & Downs, 2012). Immediately following, they filled out a 20 item Explicit Attitudes Towards Faith and Science questionnaire Reber, Slife, & Downs, 2012).

Results

The effect of environmental condition:

- Results of a t-test indicated that when examining the effect of the environmental prime, those in the science condition were significantly more biased toward faith than those in the religion condition, t(185) = 2.695, p = .008.

- There was no gender difference on IAT scores, t(185) = 1.398, p = .164.

Interaction of condition and gender:

- An ANOVA revealed that there is a marginally significant interaction for condition and gender, F(1,183) = 3.846, p = .051, indicating that females in the science condition have a significantly stronger bias toward faith.

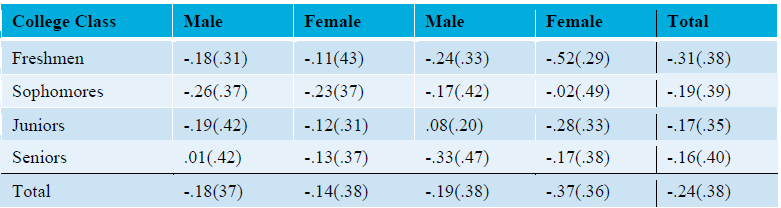

Interaction of condition and college class:

- There is a significant interaction effect for condition and college class, F(3,179) = 3.322, p = .021, indicating that freshmen in the science condition have a significantly strong bias toward faith.

Explicit Attitudes Data:

- all tests of explicit attitudes were non-significant.

Discussion

The results support the hypothesis that religious and scientific environmental primes have a significant effect on participants’ implicit attitudes about faith and science. However the effect did not fit our specific prediction. We expected participants in the religious environment to manifest a higher preference for faith over science than participants in the science environment. Instead, the opposite outcome was found: participants in the science condition, especially freshmen female participants, manifested a significantly stronger preference for faith over science. This suggests the possibility of a dialectic prime. That is, it is possible that the science environment primed these participants’ implicit religious beliefs because the concepts of science and faith may be tied to each other oppositionally in the minds of these devoutly religious participants.

One source of anecdotal evidence offers support for this interpretation. First, we conducted post-participation interviews with a random sample of 4 female freshmen participants who were assigned to the science primed environment. All of these interviewees explicitly mentioned a relationship between science and faith and all of them described the relationship using dialectic terms, like “contrast,” “conflict,” and “different.” One interviewee captured the dialectic relationship perfectly: “My perspective of science and faith and how they are similar and different has changed a lot. . . I think there are a lot of people in the world who feel like faith and science can’t exist together, and I don’t believe that at all.”

Conclusion

For these participants, science and faith are not separate or self-contained schemas. They are connected, both by their similarities and by their differences, and that relationship has to be acknowledged at some level. The interviews also showed that all of the female freshmen interviewees see college education as a challenge to faith, and that challenge has often come through science courses. A few quotations from different interviewees capture this feeling well (see Interviewee quotations in Results). These comments may indicate not only a dialectic relationship of science and faith, but also a sense of faith being threatened by science and the need to protect faith from these threatening challenges. In this sense, the unexpected results of this study may have been produced by psychological reactance.

Figures and References

Participant Demographics

- Gender: 75 Males, 113 Females

- Age Mean: 20.43

- Race: 84% White, 16% Other

- Political Mean: 5.25 on a 7 point scale from very liberal to very conservative.

- Belief in God Mean: 6.82 on a 7 point scale anchored by very strong disbelief or very strong belief.

- Spirituality Mean: 6.13 on a 7 point scale from very non-spiritual to very spiritual.

- Class: 80 Freshmen, 41 Sophomores, 40 Juniors, 27 Seniors

- Major: 70 Psychology, 99 Other, 19 Unreported

Aarts, H., & Dijksterhuis, A. (2003). The silence of the library: Environment, situational norm, and social behavior. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 84(1), 18-28. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.18

Berger J., Meredith M., & Wheeler S.C. (2008). Contextual priming: Where people vote affects how they vote. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105, 8846–8849.

Berkowitz, L., & LePage, A. (1967). Weapons as aggression-eliciting stimuli. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 7(2, Pt.1), 202-207. doi:10.1037/h0025008

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480. doi:10.1037/0022- 3514.74.6.1464

Jacob, C., Guéguen, N., & Boulbry, B. (2011). Presence of various figurative cues on a restaurant table and consumer choice: Evidence for an associative link. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 14(1), 47-52.

Kay, A. C., Wheeler, S., Bargh, J. A., & Ross, L. (2004). Material priming: The influence of mundane physical objects on situational construal and competitive behavioral choice. Organizational Behavior And Human Decision Processes, 95(1), 83-96. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2004.06.003

LaBouff, J. P., Rowatt, W. C., Johnson, M. K., Finkle, C. (2012). Differences in attitudes toward outgroups in religious and nonreligious contexts in a multinational sample: A situational context priming study. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 22(1), 1-9. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2012.634778

Milliman, R. E. (1986). The influence of background music on the behavior of restaurant patrons. Journal Of Consumer Research, 13(2), 286-289. doi:10.1086/209068

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1999). The influence of in-store music on wine selections. Journal Of Applied Psychology,84(2), 271-276. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.84.2.271

Reber, J. S., Slife, B. D., & Downs, S. D. (2012). A tale of two theistic studies: Illustrations and evaluation of a potential program of theistic psychological research. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion, 23, 191-212.

Slife, B. D., & Reber, J. S. (2009). The prejudice against prejudice: A reply to the comments. Journal Of Theoretical And Philosophical Psychology, 29(2), 128-136. doi:10.1037/a0017509

Wittenbrink, B., Judd, C. M., & Park, B. (2001). Spontaneous prejudice in context: Variability in automatically activated attitudes. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 81(5), 815-827. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.815