Garrett Nagaishi and Dr. Matthew Mason, History Department

The 1780s witnessed the rise of abolitionism within the British Empire. In its Two Reports…from the Committee of the Honourable House of Assembly of Jamaica (1788), the Jamaican government, which greatly profited from slavery and the slave trade, responded to claims made against its treatment of slaves. The report attempted to demonstrate by logic and eyewitness testimony that slavery was valuable and consistent with moral principles. Shortly thereafter, Jamaica’s ambassador to British Parliament, Stephen Fuller, published Notes on the Two Reports from the Committee of the Honourable House of Assembly of Jamaica (1789). This tract, which did not contain Fuller’s name in the original, attacked the House of Assembly’s Two Reports and condemned the way slaves were treated in the West Indies. The question is obvious: why did Fuller so forcefully speak out against the body he was meant to represent?

The funds for this project financed a visit to the Somerset Heritage Centre (SHC) in Taunton, Somerset, UK. The Fuller family had lived in Somerset for years prior to Stephen’s appointment as agent for Jamaica, and various members of his family continued to live there after his passing. The SHC holds no fewer than 35 collections relating to Stephen Fuller, some of these containing over 100 letters written by, or addressed to, Fuller.

Fuller’s Notes on Two Reports provided the impetus for this research project, expecting to find substantiation for Fuller’s disappointment in Jamaica’s treatment of slaves and involvement in the slave trade. The documents housed at the SHC, however, largely consisted of letters written to Fuller while he was in London. As agent for Jamaica, Fuller spent most of his time in England, corresponding to his Jamaican colleagues via post. While this meant there were fewer opportunities to perceive Fuller’s opinion directly, it did provide a unique opportunity that has been largely excluded from the literature. Most of the secondary sources that reference Fuller make use of papers located at Duke University or the University of the West Indies at Kingston, Jamaica, written by Fuller himself. What the Somerset papers offer, then, is a glimpse of the mindset of Fuller’s peers: those who would have had considerable influence on Fuller’s opinion and actions, especially in Parliament.

The period from 1780 to 1810 was a pivotal moment in world history. These three decades witnessed the birth of the American Constitution (1787), the French Revolution (1789), the Haitian Revolution (1791), the British abolition of the slave trade (1807), and some of the greatest intellectual and technological inventions of the Enlightenment. These are clearly not the only important events to transpire in this period, but they are representative of some of the major political, economic, and social currents at the time of Fuller’s employment as agent.

Each of the above-named events directly influenced West Indian interests. Since they had lost much of their claim to North America, the British found it difficult to trade with Americans. Competition increased, especially as American economic production expanded in the postindependence period. But while the British sought to monopolize their holdings in the West Indies and Asia, colonies such as Jamaica suffered under such mercantilist policies. Simon Taylor, a Jamaican planter who owned some 2,000 slaves at the time of his death, wrote to Fuller in 1794 imploring him to meet with Parliament to discuss opening trade with America. If they did not, Taylor wrote, the West Indian colonies must “either be withdrawn, or Perish.”1 This was not a singular example of free market principles in the Fuller papers—Fuller himself published similar tracts imploring Parliament to open trade with the wider Atlantic world.2

In 1794, a bill to prohibit trading slaves to foreign countries, an effort by Wilberforce to limit slave trading, passed the House of Commons. A letter from the Planters of the West India Colonies (based in London) wrote to Parliament arguing that such a law would create illegal markets, limit supply, raise prices, and would serve neither “policy” nor “humanity.” Rather, the bill was a “Bill of internal regulation . . . subversive of local authority,” and would eventually “annihilate trade.”3 While rhetoric of “humanity” certainly addressed moral qualms over the slave trade, the West India interest made no mistake that their primary concern with slave-trade legislation was the effect it would have on the ability of West Indian governments to operate autonomously.

By far the most recurring theme found in the documents from the 1790s was reference to the French Revolution and events in Hispaniola (Saint-Domingue, modern-day Haiti). Several letters written by Stephen and Rose (his brother) to William Dickinson, Stephen’s son-in-law, relay rumors being told from Jamaica describing the effects of the uprising in Saint-Domingue on Jamaica: “This mischief is so near us, that we cannot hope to escape it; however, we have got some warning to prepare [emphasis in original].”4 What stands out in these letters is that nearly all observations on the uprising in Saint-Domingue reflect an economic rather than a political or social concern for Jamaicans. Instead of speculating future calls for political freedom and social equality, planters worried that their slaves and “free people of colour” would be less economically productive.

What the documents at the SHC illustrate is that a significant shift occurred in the 1790s. The 1780s saw the rise of abolitionist rhetoric in Parliament and a small, but noteworthy voice of compromise in the House of Assembly of Jamaica. But events occurring in the Western Hemisphere, notably the growth of the American economy and the rebellion in Saint-Domingue dispelled much hope abolitionists had of garnering West Indian support for slave amelioration. Committed to the West India interest, Fuller held opinions of slave trading that accorded with those of ardent pro-slavery planters such as Simon Taylor. But what the literature has yet to point out is that Fuller’s position was highly influenced by events in the 1780s and 1790s, and likely shifted further to the right over time. Notes on Two Reports, then, suggested that Fuller disagreed with many of his planter colleagues, but was also a man of his time: troubled by the moral implications of his work, yet arguably more concerned about his allegiance to the House of Assembly of Jamaica and the health of the colony.

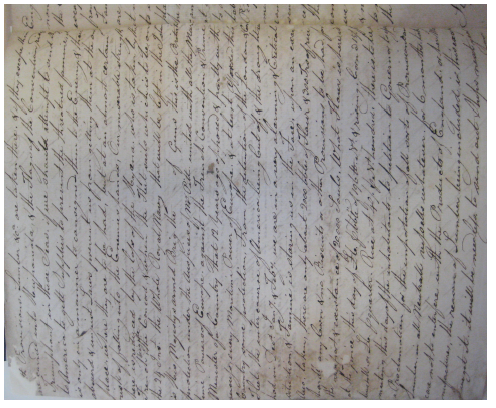

Figure 1: Excerpt of an undated letter from Simon Taylor, a Jamaican planter, to Stephen Fuller. Taylor wrote extensively to Fuller, usually emphasizing the urgency of preventing any anti-slave trade bills from being passed in Parliament. In this particular letter, Taylor says that abolitionists William Wilberforce and “[William] Pitt and his gang” were “determined to ruin the West India Islands.” Such beliefs were common among British West Indian planters beginning in the 1780s, SHC, DD\DN/508.

1 Simon Taylor to Stephen Fuller, Kingston, Jamaica, 11 June 1794, SHC, DD\DN/ 511.

2 For example, Stephen Fuller submitted a short tract to the Majesty’s ministers in 1785 saying that “nothing but a reasonable Participation in a Trade with the United States, can, on many probably Contingencies in future, prevent them from Ruin and Death,” The Representation of Stephen Fuller, Esq; Agent for Jamaica, to His Majesty’s Ministers, 8 March 1785, London.

3 Petitions of the Planters of the West India Colonies to Parliament, London, 18 March 1794, DD\DN/510.

4 Stephen and Rose Fuller to William Dickinson, 29 October 1791, London, DD\DN/262.