Jacob Jones and Dr. Ross Flom, Department of Psychology

Several studies have shown that in the first months of life, infants discriminate faces and speech sounds under a diverse range of conditions. These results suggest that infants’ capacity to discriminate faces and speech sounds changes over the course of development: Younger, but not older, infants discriminate a wider range of speech sounds and faces. Finally, studies have also shown that if infants do not continue to receive exposure to a particular language or the faces of a given species, infants may lose the ability to discriminate those speech sounds or faces. (Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens, & Lindblom, 1992; Werker & Tees, 1984; Fagan, 1972; Kleiner, 1987; Mauer & Young, 1983; Pascalis & de Schonen, 1994)

The purpose of our experiment was to examine whether human infants perform cross-species intersensory matching of faces and vocalizations. We chose to use domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) because dogs have been shown to display a range of facial expressions and barks that have been interpreted by some to include happiness, play, aggression, and fear (Pongrácz, Molnár, Miklósi, & Csányi, 2005). Moreover, it has also been proposed that through the process of evolution and domestication, dogs and humans have had substantial experience in communicating and interacting with one another, and therefore both species have become adept at comprehending the various interspecific visual and auditory communicative behaviors (Cohen & Fox, 1976; Feddersen-Peterson, 2000; Miklósi, Polgárdi, Topál, & Csányi, 2000; Pongrácz, Miklósi, & Csányi, 2001; Yin, 2002). We used infants between the ages of 6 and 24 months because infants of this age range are capable of matching human faces and voices using a variety of properties.

One-hundred and twenty-eight infants, 32 at each of the four ages, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, participated. We gathered these infants by calling their parents and asking for participation. During the phone call, we asked the parents about their child’s amount of interaction with dogs. Those parents who reported that they did not own or have a dog in the home and their child had minimal to no exposure to other dogs (<20 min per month) were eligible for participation in the experiment.

The visual events that were displayed for the infants consisted of two pairs of photographs of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris), and the auditory events consisted of four barks from different dogs.

For the auditory events, in which infants only heard one bark for each in-sound trial, we chose the two highest rated aggressive and the two highest rated nonaggressive barks. The four barks were paired with their respective faces and randomly divided into two pairings consisting of one aggressive and one nonaggressive bark. Half of the infants heard one pairing, and half heard the other pairing. Each infant received four 20-s trials: two silent and two in-sound trials. During the two silent trials, infants viewed the static images of the aggressive and nonaggressive expression/posture side by side. The silent trials were included to assess whether infants preferred either the aggressive or nonaggressive expression and also allowed us to examine whether infants’ increased or decreased their looking to each expression when it was presented silently compared with when it was presented with its appropriate bark. After the two silent trials, and just prior to each in-sound trial, the bark was presented for 2 s. Then, the two visual images were then presented for 20 s.

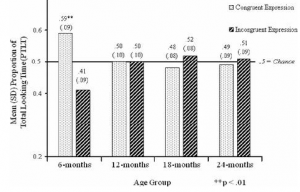

6-month-olds showed significant overall matching of both the aggressive and the nonaggressive barks independently (congruent expression). At no other age did infants match either the aggressive or the nonaggressive barks with the appropriate facial expression.

The results of this study are the first to show that infants perform cross-species intersensory matching of canine facial expressions and barks. In terms of determining on what basis infants are making the cross-species intersensory match, one possibility is that 6-month-olds perceive the common affective information from the barks and the facial expressions. The results from the current experiment, as well as from other experiments, support such a possibility. If one function or purpose of intersensory perception is to guide early learning, then, as suggested by Lewkowicz and Ghazanfar (2006), it may be beneficial to the young infant to have a broad intersensory–perceptual system in order to capture as many intersensory relationships as possible.