Kevin Blissett and Dr. Dirk Elzinga, Linguistics

The Orang Seletar and Sugut Sungai languages are endangered languages indigenous to Malaysia. With every generation there are fewer speakers of the language, and, perhaps more worryingly, the language is less frequently taught to children. It is increasingly urgent for linguists to document the languages before they vanish completely. The purpose of this project was to begin that documentation effort by translating a list of common vocabulary, known as the Swadesh list, into each of these two languages.

The data for this study was collected through face-to-face interviews with native speakers in their homes throughout Malaysia. Target words for the interviews were collected from a Swadesh list (translated into Malay). Interviewees were then guided through the process of translating this vocabulary list into their own languages. Responses from the interviewees were recorded on a digital audio recorder and then transcribed using the International Phonetic Alphabet. Interviews also included brief conversations about the linguistic genealogies of the speakers. Participants were recruited by direct contact and word of mouth and signed an informed consent document before participating in the study. For the Orang Seletar language, the subject pool included four speakers from two families living in the same village on the coast of Johor Bahru, Malaysia. The Sugut Sungai data was collected from four speakers in one family living in the city of Sandakan, Malaysia.

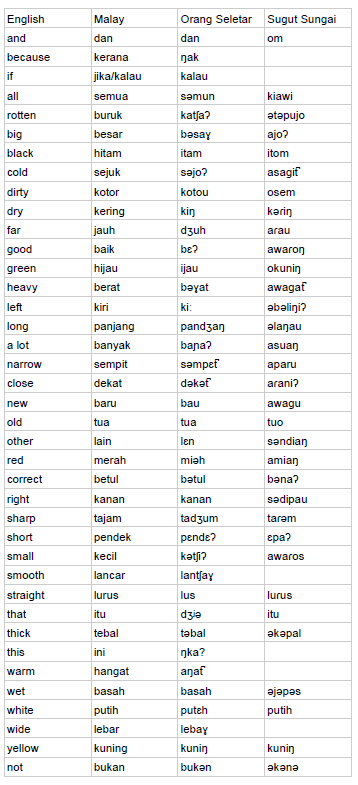

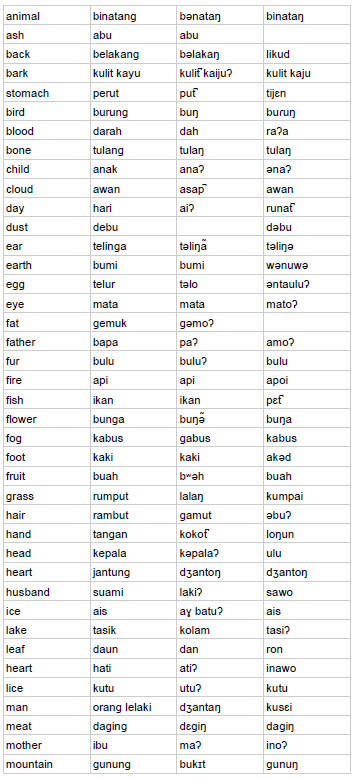

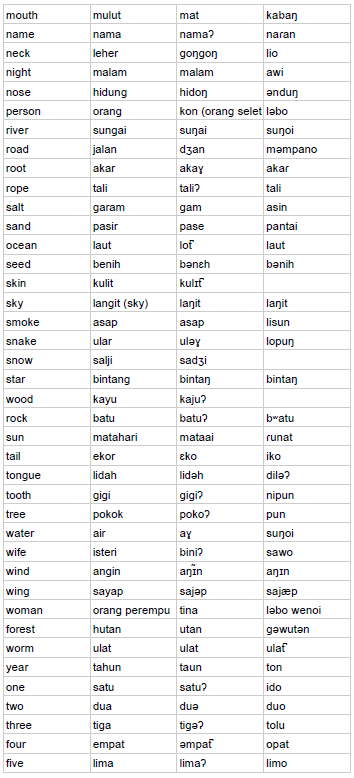

The vocabulary data collected is too large to be included in the body of the paper, but is attached it as an appendix. Because some participants were unable to translate every word on the Swadesh list into their language, one list may contain some vocabulary the other list does not.

To evaluate the health and future prospects of the languages, the second part of the study involved speaking to my study participants about their use of their language, such as how often the language was spoken to them as children, how much they are speaking it to their children, how much their parents spoke it, and so forth. This type of data is largely anecdotal, but is illuminating. While the parents and grandparents of study participants spoke their languages exclusively or most often, many of the study participants spoke Malay more often. Endangered languages were spoken frequently within their communities, but participants spent the majority of their time outside of the community speaking Malay. Additionally, while the children of study participants spoke their endangered languages with at least some degree of competency, almost all of them were more comfortable in Malay. Due to their limited competency, it seems unlikely future generations will continue to teach their endangered languages to their own children.

Many question whether Orang Seletar is a distinct language of its own or whether it is merely a dialect of Malay. Looking strictly at the vocabulary list, a strong case can be made that Orang Seletar is simply a dialect of Malay. Many of the words are exactly the same as the corresponding words in Malay; others appear to be derived through simple phonological processes from Malay words. A small group of words appears to be unique to the language with no obvious connection to Malay. These characteristics suggest a dialect of Malay and not an entirely independent language. However, there are valid counterpoints as well. For example, the language is not mutually intelligible with Malay and Malay and Orang Seletar speakers refer to them as separate languages. Additionally, there appear to be significant grammatical disparities between the two languages. At least some of the affixes critical to the Malay language do not appear in Orang Seletar. One example of this is the active meN- prefix in Malay. Many Orang Seletar verbs strip this prefix for their form of corresponding verbs. More compelling is the nominalizing -an suffix which does not appear in the language at all. As a final example, Orang Seletar appears to have a unique method of negating verbs that varies significantly from the strategy used in Malay.

After collecting the data for Sugut Sungai and leaving the city, I discovered a book on the Sugut Sungai language published by a small museum in the Malaysian state of Sabah. As far as I am aware this other project (including a vocabulary list, a phrasebook and one other work) is the only other published work on this language. I was unaware of the book before collecting my own data, so the data from this study was entirely independent. Upon comparison, the data in this study was an almost perfect match to the earlier published data, strong evidence that both sets of data are reliable.

While the data in the published collection is spelled out according to a system that seemed logical to the transcribers, the current study data has been transcribed using the International Phonetic Alphabet. Therefore, this data is a closer transcription and gives more information about the language as it is actually pronounced.

The work here is just a start. These two languages still require an enormous amount more study and recording before they will be preserved in a meaningful way. Every project has to start somewhere, however, and the work done here has moved the preservation project forward.

References

King, John Wayne., and Julie K. King. Sungai/Tombonuwo (Labuk Sugut) Bahasa Malaysia English Vocabulary. Kota Kinabalu: Sabah Museum State Archives Department, 1990. Print.

Swadesh, Morris. (1952). Lexicostatistic dating of prehistoric ethnic contacts. Proceedings American Philosophical Society, 96, 452–463.