Benjamin Holt, Dane Christensen, and Dr. Christopher Oscarson, Humanities

The roots of ecology in Scandinavia begin with the botanist Linnaeus in the 18th century, who developed the notion of the economy of nature. Throughout the 19th century, proto-ecologists carried the movement that would eventually be recognized as a legitimate and viable science, studying the interaction between organisms and their environment. Leading up to the turn of the century, the climate in Scandinavia was ripe for organizations to emerge such as the Svenska Turistföreningen (Swedish Tourist Society) and the Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen (Swedish Nature Protection Society), both of which are committed to improving and preserving nature in Sweden.

Each of these organizations publishes yearly journals to document developments in nature protection legislation, preservation, exploration, interaction, and other affairs related to nature and ecology in Sweden. These journals served as the foundation for topic modeling analysis of ecological thought in the country. Our purpose was to reveal a comprehensive, interdisciplinary picture of how both aesthetic and scientific discourses led to a radically reconfigured idea of the human relationship to the environment in turn of the century Sweden. Though our involvement in the project has largely come to a close, the project itself will continue to grow and include other corpora like journals, articles and other publications from all regions of Scandinavia and from varied fields of study.

Computer-aided text mining and topic modeling allowed us to examine text corpora of the Turistföreningen and the Naturskyddsföreningen from an intensive analytical standpoint. Ultimately, we were able to produce topic models of each journal that offer valuable and unique views of trends in the development of Swedish ecological thought. In order to do so, however, we first had to prepare these bodies of text for analysis. Naturally, we began by collecting the yearly publications from both the Turistföreningen as well as the Naturskyddsföreningen. Many of these were available digitally; for those that were not, we obtained physical copies and digitized them ourselves. We then converted the digital files to readable text files. These were further separated into individual “chunks” of relevant data (tables of contents, advertisements, and other non-useful materials were omitted), which are generally individual articles. With this done, we could then subject these pieces to rigorous data and text mining, producing topic models of recurrent (and therefore significant) words and phrases.

We developed a computer program to streamline and aid in the preparation of the texts for analysis. This program separated and appropriately named publications by article. Additionally, we aided in the development of a website hosted by the Humanities Lab where all results and analyses will be available. The process of preparation and analysis we established will be the exact procedure Dr. Oscarson will have future research assistants use.

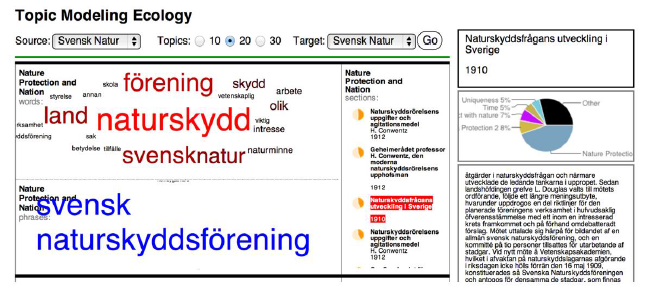

Our preliminary analysis could be run using 10, 20, or 30 topics; based on this experience, future analyses will be run using 20, 25, or 30. This process provides users with groups (in the form of a word clouds) of related words and phrases. These are sized according to prevalence. In addition, the user is provided with a list of articles that are the most saturated with the given topic; he or she can then click on individual articles to see, alongside the results, the content of these articles along with a more exact breakdown of contents.

Our preliminary findings were presented by Dr. Oscarson at the Society for the Advancement of Scandinavian Study (SASS) at Yale University in March of this year. Even this preliminary analysis produced interesting and intriguing results. For example, the analysis program formed a topic based on common words like “there”, “come”, “go”, “now”, “large”, “here and there”, etc. Upon examining the articles saturated with these keywords, we found these to be largely fiction articles – the program had formed a model of “Stories”. Even more interesting, these seemed to be almost exclusively found in the Turistföreningen’s publication. Contrastingly, topic models for both “Birds” and “Trees” were created and found to be highly concentrated in the Naturskyddsföreningen’s texts. The evolution of these texts (as one looks through how the results change over time) suggest a different view of nature in the earlier years of these societies – one that has no concept of the integration of nature as a whole, and is instead focused on the protection the individual: the tree, the bird, etc. Another trend reflected is that of industrialization; one model created involves tourism in Northern Sweden, an area made publicly accessible thanks only to the arrival of industry in Sweden. The future promises even more interesting results, as Dr. Oscarson continues to improve analysis methods and add additional and more varied bodies of text.

This project has established the foundation for further studies with nature texts (as well as texts from other areas). We have, from scratch, created a set, streamlined methodology for preparing and analyzing texts, which will simplify and expedite future topic modeling and text mining projects. We have also provided a foundational body of research that will contribute source and reference material for Dr. Oscarson’s upcoming book about the Ecological Imaginary in 19th and 20th century Sweden.