Kiira Fox and Dr. Renata Forste, Sociology

Main Text

While previous research indicates child stunting rates have decreased in the aggregate over the last few decades, malnutrition continues to account for over half of annual child deaths and the stunting of 226 million (Neumann et al.). As national inequality persists, even increasing in certain areas, higher rates of stunting have become concentrated within already disadvantaged populations (Minujin and Delamonica, 2004). Africa, for instance, has particularly low educational attainment, high rates of poverty, a lack of infrastructure and experiences stunting rates as high as 60% in certain areas (Neumann et al.). Although earlier studies have identified many dimensions of disadvantage that promote malnutrition, lack of education is consistently associated with poor health outcomes. Not yet fully understood, however, are the pathways through which education influences nutritional status. The purpose of this study was to examine several avenues through which maternal education influences child health in Africa. This knowledge will hopefully engender solutions that address the specific challenges faced by disadvantaged populations and ultimately help them achieve better child nutritional outcomes.

In this study I used Demographic and Health Survey data, nationally-representative household surveys collected from 25 African countries between 2000-2009: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The sample size was 95,778 children under age five. With this data set I model the relationship between maternal education and child nutritional status, and examine four mediating mechanisms: Socioeconomic factors, attitudes, knowledge and reproductive behaviors. I used the WHO’s definition of stunting, standard deviation from median height-for-age, as a measure of nutritional status. The model was estimated using ordinary least squares regression, controlling for place of residence and the child’s age. I presented my research at the Mary Lou Fulton Conference April 8, 2010 at Brigham Young University.

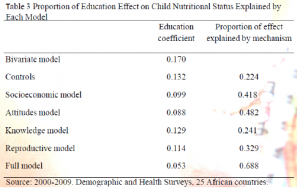

The results indicated that in total 36% of the children in this analysis are stunted (two standard deviations or more below median height-for-age). All of the mediating mechanisms modeled were significant, with the exception of one measure of reproductive behavior: birth order. The attitudes model accounts for the greatest portion of the relationship, followed by socioeconomic factors and then reproductive behaviors. Health knowledge has the smallest effect. These findings diverge from previous studies in other countries that have found socioeconomic status to be the most important factor (Frost et al., 2005). Altogether 69% of the maternal education effect on child nutritional status is accounted for by the mechanisms measured. While further research should be conducted to identify omitted mediating factors, these results do highlight the importance of women’s access to and utilization of modern health care as well as increased economic opportunity in improving the nutritional status of the children in Africa.

There were a couple of challenges that arose as I pursued this project. Perhaps my initial struggle was that the relationship I originally wanted to examine proved to be completely uninteresting. Using the same data set I had run a different model examining the effect of maternal education that provided essentially no new or unique information. Unsure of what research question I should examine, I returned to my literature review to identify gaps in previous research that I might address with this study. Because the Demographic and Health Survey data set I had is really extensive and I have always been interested in child outcomes in Africa, I was hoping to pursue a project along the same vein as the idea I initially proposed. I had read many studies attesting the importance of maternal education and I wanted to better understand how mother’s education has such a great effect on child health outcomes. After recognizing that the pathways through which education affects child stunting in the African context remains little understood, I decided to pursue this new research question. Using the same data but a different model proved to be much more effective and yielded new insight into the relationship.

My research did not turn out exactly how I was expecting. A similar study has been conducted examining the mediating mechanisms between maternal education and child nutritional status in Latin America (using a different data set) and the results differed significantly. Frost et al. (2005) found that socioeconomic status accounted for the highest portion of maternal education’s effect on child nutritional status. This is perhaps evidence of greater wealth disparity in Latin American countries versus African nations which tend to be more homogeneously poor. To really understand the differing regional results, however, additional research is required; other regions of the world should be examined as should additional mediating mechanisms. I was also surprised that the mediating mechanisms I used accounted for such a great percentage of maternal education’s effect on child nutritional status. I was not expecting attitudes towards modern health care to explain the largest portion of that effect and I would really like to include more relevant indicators to see how the strength of that relationship is affected.

References

- Frost, Michelle Bellessa; Forste, Renata and David W. Haas. (2005). Maternal education and child nutritional status in Bolivia: finding the links. Social Science and Medicine 60: 395-407

- Minujin, Alberto and Enrique Delamonica. (2004). Socio-economic inequalities in mortality and health in the developing world. Demographic Research Special collection 2 13: 331-35.

- Neumann, Charlotte G.; Gewa, Constance and Nimrod O. Bwibo. (nd). Child Nutrition in Developing Countries: Critical Role in Health. UCLA working paper.