Sierra Debenham and Dr. Erin Bigler, Psychology

Main Text

I evaluated the Montreal General Hospital’s use of the anti-seizure medication phenytoin in all traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients admitted to the hospital over the course of 2 years. I then evaluated the information to evaluate how effective the phenytoin treatment was in preventing early TBI.

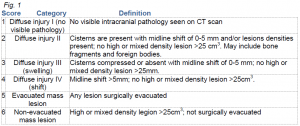

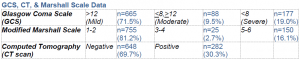

I retrospectively analyzed the medical records of all TBI patients (1083) admitted to the Montreal General Hospital’s tertiary trauma center from 1 April 2007 – 31 March 2009. 153 patients were excluded due to incomplete data sets (e.g., missing GCS). From the patients’ charts, we recorded their age, initial GCS, CT scan results, and phenytoin administration information. I scored the CT scans according to a modified Marshall scale; each patient was assigned a number between 1 and 6 (see figure 1).

From the patients’ medical records, we recorded the toxicity of phenytoin according to the phenytoin and albumin levels in the blood during the time of treatment. Phenytoin is toxicwhen concentrations in the blood are > 80 μmol/L in the blood. The administration of phenytoin was evaluated according to a) bolus given; b) date of bolus; c) maintenance dose, date, frequency, and duration; and c) route (IV, oral, etc.)Compliance was analyzed by counting the number of times phenytoin given to patients within a seven-day window post-trauma and comparing it to the number of times it was given outside of that time period.

In order to determine which factors physicians used to decide when to administer phenytoin, we used a logistic regression to determine the relationship between initial GCS, CT results, Marshall Scale and the administration of phenytoin. We analyzed patient outcome by recording the incidence of early PTS as well as complications associated with the treatment, including adverse reactions and abnormal serum levels.

Patients with a positive CT scan were most likely to be given phenytoin, suggesting that the primary parameter used to decide whether to administer phenytoin was the CT scan results (p<.001), rather than the initial GCS or the amount of blood on the brain, as defined by the Marshall Scale score (GCS: p=.802 , Marshall Scale: p=.704).

Phenytoin reached toxic levels in 13.9% of patients; however, there were no significant adverse reactions. Administration of phenytoin in patients who had a negative scan was not a significant cause of toxicity – only two such patients had a recorded instance of toxicity.

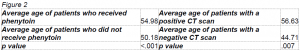

The average age of patients who were given phenytoin was nearly 55 years, while the average age of patients who were not given phenytoin approximately 50 years (see figure 2). Older patients were therefore more likely to receive phenytoin treatment (p<.001). However, it is important to note that older patients were also more likely to have a positive CT scan (p=.007).

5.38% of patients had early PTS; however, nearly half (42.8%) of those had immediate seizures, bringing the total percentage of early PTS to 3.08%.

Discussion

As a result of my study, I recommend phenytoin prophylaxis as a standard treatment for TBI patients with a positive CT scan. I also highly recommend checking phenytoin levels at least once within 7 days after the first administration to prevent toxicity or underdosage.

Compliance with AANS Guidelines Physicians adhered to the AANS recommendation of administering phenytoin within the first 7 days post-trauma 100% of the time.