Michael Davidson and Dr. Joel Selway, Political Science

The provision of public goods is, on average, significantly poorer in ethnically-diverse communities (Banerjee et al. 2005). Three potential mechanisms have been put forward to explain this phenomenon: preferences, technology and strategy selection (Habyarimana et al. 2007). While the landmark experiment on this topic concluded that strategy selection best explained poor public goods provision, we posit that the role of preferences is significant (ibid.). The lab experiments we conducted tested for differences in preference between ethnic groups in the Southeast Indian city of Chennai.

Habyariama et al. concluded that in-group reciprocity norms and ethnic technology (common cultural material-language, experience, understandings) make public goods provision easier within homogeneous communities. In-group reciprocity norms include expectations that noncontribution to public goods might yield punishment from co-ethnics. Ethnic technology can take the form of a common language or shared cultural understanding which facilitates cooperation (ibid.).

Building on the work of Habyariama et al., Harris and Findley preformed experiments in South Africa testing the ability of ethnics to identify members of their own ethnicity and others (2009). Their findings showed that identifiably was on average very poor. However, they did show that individuals who more strongly identify with their own ethnic group had greater success at correctly identifying other ethnics.

We hypothesize that the third proposed mechanism, preferences, plays a greater role than attributed by the above mentioned researchers. While this research has been presented in the context of public good provision, it has applicability to other collective action problems.

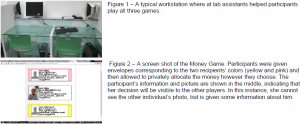

Our participants played a series of games to study the effect of ethnicity on people’s behavior, decision-making and preferences. The first of which is known by economists as the ‘dictator game.’ In this game, randomly sampled participants distribute money between themselves and two other individuals whose photographs appeared on a computer screen. The participants and those to whom they gave money actually kept/received any money they were allotted. Our hope is that by analyzing these patterns, we can learn about why cooperation between diverse groups is, on average, so poor.

The second game tested the ability of participants to identify the caste of others. A small monetary reward was given for each correct guess when a random individual’s photograph was displayed.

The third and final game participants played before proceeding to the exit survey was lightheartedly called the beauty game. In this game, participants were asked to assign the image of an individual a beauty score between one and five, excluding gender, with five being very attractive/beautiful/handsome. The results from this game allow us to control for any influence the beauty of the recipient might have had on giving patterns.

The analysis of the games results is a tedious and laborious activity, which we expect will take until the first of next year to complete. Preliminary findings, however, are supportive of one of our hypotheses, that on average, it is difficult to learn a person’s ethnicity from a portrait alone. Should this be true in the final analysis, it would add external validity to the South African study’s findings. We anticipate that the value of our findings will lend to publication in one of our discipline’s leading journals.

I was very fortunate to work with Dr. Selway. In addition to being a great companion in India, he showed me how culture, like the one I was seeing for the first time, is a big part of my life, as a Latter-day Saint and as an American. His knowledge and experience were invaluable when it came to designing and carrying out the research.

Researching in India provided me with a hands-on lesson in sampling and data collection. I learned how to prepare and conduct an experiment at every stage, including writing proposals, fine tuning our ideas and plans, making contacts on the ground, writing survey questions and detailed instructions for the participants and the assistants, and correcting last minute errors and computer glitches. In addition, I learned how to use the Qualtrics survey software and became more technologically savvy as I often found myself as the sole system administrator.

The practice of carrying out real, significant research was valuable, however, my learning, especially about culture, came from many different experiences. On one occasion, Dr. Selway and I were talking with our friend and fellow researcher, Jerome Samraj, about our predictions for the ethnic identification game. He asked us to identify the caste of the six first year MBA students who had been helping us throughout the project. We named one individual who we felt certain must be from the most forward, Brahmin caste. Jerome chuckled. It just so happened we had named the only non-Brahmin among them. We were shocked. There were people of all skin tones and physical builds in the group. Needless to say, even before our findings showed that appearances rarely reveal caste, I had learned a tremendous lesson.