Keara Moyle and Dr. John Hawkins, Anthropology

Introduction

Within the last two decades, the White Earth reservation of Ojibwe has seen a dramatic resurgence of interest in and performance of what they would call traditional culture. This traditional culture has played a critical role in tribal membership and concepts of identity. The White Earth reservation underwent constitutional reform from 2007 to November 2013, which included new legislation determining membership. After years of an imposed policy of blood quantum, White Earth residents are basing their membership on a system, considered by some, to closely follow the traditional ways of determining tribal membership.

Methodology

I spent nearly fourteen weeks on the White Earth Indian reservation in northern Minnesota. While there I conducted an ethnographic study, focusing on the proposed constitution and its implications on citizenship/membership requirements and what that means for perceptions of identity. I was constantly engaged in participant observation, taking extensive field notes each day of my study. I connected to informants by the snowball method—I made contact with a few individuals upon arrival and they introduced me to others, who introduced me to others, etc. After spending time to build somewhat of a relationship between the informant and myself, I conducted structured and unstructured interviews. All questions were open-ended and allowed the informants to expand on the issues they believed to be important. I was able to conduct these interviews with 28 different informants—ranging in age from 18 to 77, eleven women, seventeen men. I also attended almost every single constitution educational community session. Out of the twenty-two sessions held from May to August 2013, I attended nineteen. This put me into direct contact with 228 community members. Roughly one-third of the members who attended these meetings spoke up, asked questions, and let their opinions be heard. At the end of one of these meetings I was able to lead a focus group of eight community members, using the same questions I used in my interviews. At the end of each week I contacted Dr. John Hawkins via email or phone and he advised me and help guide my ethnographic methods.

All claims that are made in this paper stem from my interpretation of the observations I made and the information I gathered from methods used. If any opinion or idea is misrepresented it is due to my own fault and misinterpretation, and should not reflect on the people and community. As promised to all informants, their anonymity will be respected and no one’s real name is used.

Results

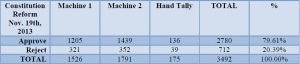

The proposed constitution passed by almost 80% of the vote. 2,780 members of the White Earth nation voted to pass the constitution, which includes the end of blood quantum and the adoption of lineal descent as the new way to determine tribal membership.

Discussion

In almost every single interview I conducted, there was mention of the “Indian way” and its importance in determining membership into the tribe. When I spoke with a respected spiritual leader, who also is a fluent Ojibwe speaker, about this concept he told me this idea is Anishinaabezhitwawin, or the way of the ones who first walked the earth. These are the teachings of the old ones. And Anishinaabezhitwawin is the sense of identity within the tribe. This extends beyond the personal self, bonding each individual to the tribe and to the Anishinaabeg dok, or all Ojibwe people. All questions of membership and identity can be answered by the ones who first walked the earth. This teaching is deeply rooted in the people’s perceptions of what it means to be a member of the tribe and to be Anishinaabe.

Membership and acceptance into the tribe was never determined by skin color or blood measurement. That was a completely Western categorization that was imposed upon the people by federal policy like the Dawes Act of 1887 or the blood quantum requirements of the 1960s. As one tribal elder put it, “We never asked what your blood measurement was. How do you even measure blood? We knew who was Anishinaabe and who wasn’t. Did they live with us? Did they work with us? Did they know the Indian way? Then they are Ojibwe”.

The sense of membership and identity in the tribe goes deeper than the skin. Anishinaabezhitwawin is a way of life that must be respected and honored. Individuals must make a conscious decision to honor their identity as an Ojibwe, and one way to do that is to learn and to become involved with the community and its traditions. One woman said to me, “I feel for those in my community who don’t have any Indian blood left. They’re more Indian than some full bloods. That’s what it’s all about– their participation and affiliation with the community. People shouldn’t be enrolled if they aren’t affiliated”. One man who has lived on White Earth all his life also said, “I don’t have enough blood, but ask anyone, I’m more Indian than most enrolled members here. I put down my tobacco. I pray. I drum. I sing. I go to lodge. That’s a lot more than what most can say. But I know who I am”.

Anishinaabezhitwawin provides a way for individuals to know who they are based on their connection to their ancestors, their land, their language, and their customs. The members who are firmly rooted in this understanding do not question what it means to be White Earth Ojibwe or a member of the tribe. As one woman simply stated, “What makes me Indian is the fact that I live the Indian way. I have no idea how much Indian blood flows me. But that doesn’t or at least, it shouldn’t matter. I am Anishinaabe”.

Membership in the tribe does not come from blood or an enrollment card; it comes from the traditional culture. One spiritual leader said, “Our ways are what make us Anishinaabe. It is not reliant on any little card or enrollment number or certification of membership. If we live our way, speak our language and sing our songs, then we are Anishinaabe.”

Conclusion

This is an emerging discussion on the concept of identity at the White Earth Indian reservation. With more claims come more questions and more discussion. I continue to work with the data collected and am currently working on a senior thesis for the Anthropology department, with hopes to publish.