Megan Christensen and Dr. Mikle South, Department of Psychology

Autism is a severe neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impaired social interaction and communication. Anxiety is also an extremely common feature with approximately 81% of children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder also qualified for at least one other anxiety disorder (Amaral et al., 2003). Amaral et al. (2003) have shown that monkeys with bilateral amygdala damage lack of fear in typically threatening social situations. Blanchard et al. (2001) have shown that humans react to hypothetical fearful scenarios in much the same way that rats do in actual threatening situations, i.e. “freezing” or run away depending on the level of danger.

We recently adapted the Intruder Paradigm for Humans from studies of emotion regulation in monkeys (Kalin, 2003). Three distinct phases occur while the participant attends to a computerized cognitive task: 1) the attending research assistant leaves the room for a short time, leaving the participant alone; 2) after the RA returns, an ill-dressed male confederate enters the room and begins an argument with the RA until both leave; 3) the confederate intruder re-enters the room but does not engage the participant. This is the most ecologically valid study in autism that we are aware of, allowing connections both backward to animal models and forward to real life application in people with autism. My project provided a detailed study of behavioral reactions to this situation as captured on videotape.

To study the behaviors, I took the video recording previously made of each participant in the Intruder Paradigm for Humans and coded each video for behaviors in five categories that include body movement, head movement, limb movement, facial movement, and vocalizations. The videos were broken down into one-minute sections that correspond to nine specific events in the experiment. The segments were randomized and then randomly distributed to trained video coders who were blind to diagnosis. Each video was watched by two different raters and checked for inter-rater reliability using an interclass correlation.

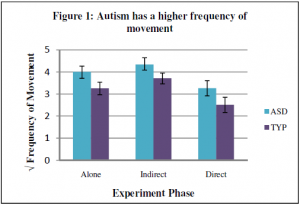

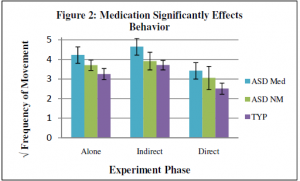

The results showed a couple of different things. First, the participants with autism moved significantly more than the control group as seen in figure 1. The autism group, however, reacted in a similar pattern as did the control group. This suggests that while their responses are not quite typical, they are on the right track. Another finding showed that medications are helpful in controlling the behavioral response of children with autism. Figure 2 shows a comparison between the three groups and we see that those participants with autism who were also taking any type of medication to help control their anxiety reacted behaviorally within a typical range.

This project was challenging. It took longer than expected to code all the videos and sort through the enormous amount of data. I wanted to be more specific with the coding, but limited time and resources did not allow me to be as in depth as I wanted to be. Another challenge was reliability. We worked hard to keep everyone on the same page and when we ran into problems we talked them out together which allowed for our group to remain very reliable in the end.

This project has given me many opportunities to share what I have learned with others. I was able to combine these results with other research assistants in my lab and learn about how the body responds both behaviorally and internally to anxiety and then begin tracing these reactions back to a genetic level. We were able to present these results and conferences including: The Utah Conference of Undergraduate Research, The Rocky Mountain Psychological Association, The Marylou Fulton Conference, The President’s Leadership Council, and The International Meeting for Autism Research.

Future studies are needed in the study of anxiety in autism. People are complex and view the world in many different ways and so we must continue to explore the different sources of anxiety. I would suggest that future studies using a similar model of video coding should look into more advanced computer software that would allow for faster and more detailed coding of the videos.

Many thanks to Mikle South, Tiffani Newton, Kyle Jamison, Elaine Huntsman, Whitney Ernst, Paul Chamberlain and many others who contributed to this project.

References

- Amaral, D.G, Bauman, MD, Schumann, C. Mills. (2003) The Amygdala and autism: Implications from non-human primate studies. Genes Brain and Behavior, 2(5), 295-302.

- Blanchard, D. Caroline, Hynd, April L., Minke, Karl A., Minemoto, Tiffanie, Blanchard, Robert J. (2001) Human defensive behaviors to threat scenarios show parallels to fear and anziety-related defense patterns of non-human mammals. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral

Reviews, 25(7-8), 761-70. - Kalin, Ned H. (2003) Non-human primate studies of fear, anxiety, and temperament and the role of benzodiazpine receptors and GABA system. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64(3), 41-4.