Justin Stark

People encounter and make decisions constantly. Trivially, we may need to decide which color blue better matches our eyes or, significantly, we may be asked to make a decision as participants in a jury, a decision that could affect the rest of someone’s life. Some of the more important and influential decisions we make are moral decisions. There has been a lot of interesting research analyzing and discussing moral decisions and the studies range in discipline from neuroscience to philosophy. Some of this research has suggested that language can play an important role in our decision-making processes as well as in our perceptions of events, people and ideas (Boroditsky 2011). Language use can effect our perception of differences in the qualities of colors or even affect the way we understand fault and causality in a legal case.

Joshua Knobe, an experimental philosopher, has raised some interesting questions and given suitable answers in in describing a phenomenon that he calls “intentional action in folk psychology” or how a layperson judges the intention of others. It is more popularly called the “Knobe Effect”. Knobe observed this phenomenon after presenting to bystanders a specific moral situation, decision and outcome. He then surveyed the layperson’s moral judgment of the decision in the mock situation. The phenomenon is that there seems to be a judgment bias towards the negative outcome. His paper “Intentional Action and Side- Effects in Ordinary Language” philosophically describes this phenomenon. Joshua Knobe gave bystanders in a park the following situations:

The vice president of a company went to the chairman of the board and said: “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits, but it will also harm the environment.” The chairman of the board answered: “I don’t care at all about harming the environment. I just want to make as much profit as I can. Let’s start the new program.” They started the new program. Sure enough, the environment was harmed (Knobe 2003).

Knobe then asked the bystander if the chairman intentionally harmed in environment. For the second scenario, Knobe replaced the word “harm” with “help”

The vice president of a company went to the chairman of the board and said: “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits, and it will also help the environment.” The chairman of the board answered: “I don’t care at all about helping the environment. I just want to make as much profit as I can. Let’s start the new program.” They started the new program. Sure enough, the environment was helped (Knobe 2003).

Again, Knobe asked the bystander if the chairman intentionally helped the environment. Interestingly, eight out of ten of those presented with the first scenario (environment harmed) blamed the executive for the negative outcome while only 3 out of 10 believed that the executive in the second scenario intentionally helped the environment. This asymmetry is the subject of much of the literature surrounding intentional action and is popularly known as “The Knobe Effect.” Joshua Knobe explains this phenomenon this way:

There seems to be an asymmetry whereby people are considerably more willing to blame the agent for bad side-effects than to praise the agent for good side-effects. And this asymmetry in people’s assignment of praise and blame may be at the root of the corresponding asymmetry in people’s application of the concept intentional: namely, that they seem considerably more willing to say that a side-effect was brought about intentionally when they regard that side-effect as bad than when they regard it as good (Knobe 2003:7).

This phenomenon, I believe, deserves a linguistic analysis. Using language as a variable I hope to gain a greater understanding of this phenomenon. Specifically whether variation in the language presented to subjects creates variation in their responses. If language is a lurking variable in Joshua Knobe’s research then we should expect to see statistically significant variation in the results when such a variable is adjusted in the study.

1. A LINGUISTIC VARIABLE.

It is apparent in Figure 1 through the use of keyword in context concordance lines from The Corpus of Contemporary American English that the language used by the chairman of the board when he replied “I don’t care at all about harming/helping the environment” in Knobe’s Vignette is most commonly associated with expressions of disregard and contempt (Davies 2008-). Figure 1. Keyword in Context Concordance Lines for “care at all about” Though it is unclear why Joshua Knobe chose to use this specific phrase in his vignette it is clear that there are many other expressions in English that are similarly used, many of which to carry either more neutral or more contemptuous semantic features. For example “not so concerned about” seemed to be much less associated with disregard and contempt in English when observed using KWIC concordance lines in COCA as seen in Figure 2.

Given the variety of phrases used to express attitudes ranging from apathy to disregard and contempt a question arises as whether such a variation in meaning could be observed as a lurking variable in Joshua Knobe’s study. It does seem that Knobe was not careful about his language use. The two vignettes are not identical in every way besides the side-effect of either helping or hurting the environment. In the vignette where the environment is harmed, the vice president says, “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits, but it will also harm the environment.” Whereas in the vignette where the environment is helped he says, “We are thinking of starting a new program. It will help us increase profits and it will also help the environment.” This difference, the use of the word but versus the use of the word and may be inconsequential or it may indicate a lack of awareness about language as a variable. The meaning of the two vignettes differs in more than just helping or harming the environment. The word but expresses contrast, that is, making money is good, and in contrast, harming the environment is bad. Thus the moral status of the side-effect is clearly framed by the vignette where the environment is harmed while it is neutral to positive when the environment is helped.

Though this question has not yet been discussed widely in academic journals there is evidence than language can play a significant role in human thought and decision-making (Boroditsky 2011).

Language itself is full of metaphor and those associations are present and influential in our reasoning (Thibodeau, Boroditsky 2011). Priming even with what may seem like trivial differences can significantly alter perception and memory (Loftus, Palmer 1974). Certainly language can influence human judgment and so it is reasonable to question the role of language in Knobe’s experiment, specifically whether language is a lurking variable in this phenomenon.

The statistical significance of such a lurking variable would be to open questions about not just the method used by Joshua Knobe but also some of his fundamental assumptions about this phenomenon. It is plainly asserted in Knobe’s writing that it is the moral status of the sideeffect (in this case harming the environment) that correlates to the asymmetry in these studies. If the language of the chairman of the board, whom we will call the actor, is correlated to the asymmetry (indicated by language as a significant independent variable) then it may not be the moral status of the side-effect that determines the asymmetry but perhaps the perceived moral status of the actor himself. This would be a significant contribution to the study of intentional action.

2. NO SIGNIFICANT LINGUISTIC VARIABLE.

This phenomenon observed by Joshua Knobe is remarkably robust. It has been replicated several times, testing for new variables it and consistently provides the same asymmetry (Knobe 2003, 2004, 2006). It seems on all counts that there is indeed an asymmetry in the judgment of intention when there is a sideeffect with negative moral status. If this research shows no significant variation in results when language is administered as an independent variable it will be yet another verification for the legitimacy of this phenomenon of intentional action and consequentially will strengthen the argument that the asymmetry observed in this phenomenon is indeed a consequence of the moral status of the side-effect, not in consequence to the moral status of the chairman of the board in this vignette based on the nature of his language.

3. METHODOLOGY.

In order to assess whether language is a significant variable in the phenomenon popularly observed and described by Joshua Knobe I have created several variations in the language of the vignette. Specifically, I have created variations in the language used by the chairman of the board, since it is his intentions the subjects of Knobe’s survey were asked to determine. These variations will be substituted into the vignette in the place of “I don’t care at all about the environment” and were created specifically with the purpose of altering the expression of the chairman of the board to language that is either more or less associated with contempt and disregard. This is done using word choice, idioms and hedging. Thus these variations will be our independent variable of language and our subjects’ evaluation of intention will be our dependent variable of judgment. By replicating Joshua Knobe’s survey about the chairman of the board with the added language variables (as well as the original language as a control), we should be able to observe whether language is a significant variable in this phenomenon of intentional action. These expressions are as follows:

(1) a. I don’t care so much about the environment.

b. I don’t really care about the environment.

c. I’m not concerned about the environment. d. I’m less concerned about the environment.

e. I’m not so concerned about the environment.

f. I’m not really that concerned about the environment.

g. Who cares about the environment?

Categorizing these expressions on a scale along either more or less disregard is essential to understanding the results of this study. However, such determinations are by nature subjective and often a consequence of the subject’s perceived value of the object in the argument (whatever it is we do not care about), such as the environment in this case. In order to create some consistency and credibility these expressions will be reviewed and ranked by a group of peers using a Qualtrics survey. They will be ranked along a scale from 0 to 10 as expressing less or more disregard. The results will essentially be subjective, but the ranking will be based upon group subjectivity.

The expressions that are ranked as the minimum, median and maximum will be selected as variables for our replication of Joshua Knobe’s study. By this method we will have created a less subjective and more appropriate evaluation of our independent variables. For example, if a particular phrase, such as “who cares about” is ranked as expressing maximum disregard it is to be hypothesized that the use of this phrase in Knobe’s vignette would impact the results differently than the phrase that was ranked as expressing the minimum disregard. The phrases will be kept in the context of caring about the environment in this preliminary survey as to reduce the variables in a subject’s judgment of disregard in both this preliminary survey and it’s relation to the final survey.

The final survey will be a replication of Knobe’s original survey using his vignette about the chairman of the board with the new phrases inserted. This survey will be administered to a more general audience than the survey previously discussed, which will only be administered among peers. The survey will be administered using Qualtrics and will be distributed through social media and email. Each subject will be shown only one version of the vignette. Though the convenience of this sample is questionable, this sample will likely be more scientific than Knobe’s original survey which he conducted himself by approaching bystanders in a public park. Another significant difference in the Qualtrics survey will be four answer options instead of just yes and no.

The subjects will be able to answer the question of “Did the chairman intentionally help/harm the environment” by selecting any of the following: definitely not, probably not, probably yes, definitely yes. This will allow for greater sensitivity in determining any effect of the independent variables (the phrase variations) on the dependent variable (the subjects’ judgment of intention). Significance will be determined in with a p-value of < .001. In order to evaluate the significance of any variation in responses to the added language variables a chi-square statistical test will be used.

4. ANALYSIS.

The preliminary survey was administered to a sample size of N=10 and provided clear maximum and minimum rankings of disregard for the expressions in example (1). Expression d. (I’m less concerned about the environment) received an average score of 1.22 out 10 for level of disregard; this was the minimum. Expression g. (Who cares about the environment?) received an average score of 7.52 out of 10 for level of disregard; this was the maximum. The median was expression a. (I don’t care so much about the environment) and received a score of 4.86 out of 10 for level of disregard. These three expressions in addition to Joshua Knobe’s original vignette were included in the final survey.

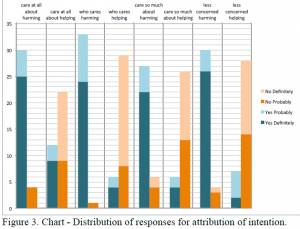

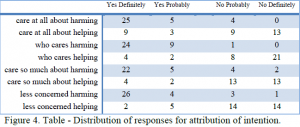

The final survey was administered to a sample size of N=271. This survey included the 4 expressions mentioned above with both the positive and negative side-effect (harming or helping the environment). It is clear from the data that the same asymmetry of responses between the positive and negative side-effects, which were first observed by Joshua Knobe in his 2003 experiment, has been replicated in this study. This asymmetry is apparent in figures 3 & 4. The grouped columns show the distribution of the responses to the question, “did the chairman intentionally harm/help the environment.” Our control, the repetition of Knobe’s original vignette with the chairman using the phrase, “I don’t care at all about” maintained its high statistical significance with a chi squared p-value of < .001. All other variations (using expressions d., g., and a.) resulted with the same statistically significant asymmetry as the control, all with p-values of < .001.

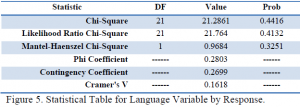

Not only was this asymmetry replicated in this study’s results but there is no statistical significance found in any variation of the distribution of responses for the added language variables (expressions d., g., and a.). The results of the chi-squared test for significance are listed in figure 5. The calculated p-value for the chi-squared table are all > .1 and are far from statistical significance. If language were a lurking variable in this phenomenon, then one would expect to see significant variation in the results when the language variable is implied. Since no significant variation was observed there is no significant language variable to the extent that this study has tested for one, thus further supporting the results obtained by Joshua Knobe.

5. CONCLUSION.

An important argument in Joshua Knobe’s analysis of this phenomenon is that the asymmetry is a consequence of the moral status of the side effect. These findings, specifically that the language of the chairman is not a significant variable in the phenomenon, uphold this argument. If the moral status of the agent were playing a role and if an expression of contempt or disregard is a clear manifestation of the negative moral status of an individual then an expression of contempt or disregard should create significant variation in the distribution of responses and thus provide evidence that the moral status of the agent is playing a role. However, since no such significant variation was observed, the only apparent variable is the moral status of the side effect or, in this instance, whether the environment was harmed or helped.

Though the results of this study have only replicated and supported previous work, it is another important step in understanding this phenomenon, which is far from trivial. The Knobe Effect undoubtedly has many implications both academically and socially.

Perhaps one of the most obvious and serious implications is in our legal system. Intent is written into many of our laws as a definition feature for many crimes, murder being the most obvious. Could it be true that jurors are more likely to perceive intent merely as a consequence of the moral status of killing? This judgment of intent is the difference between murder and neglectful manslaughter and an investigation into the mechanism of how humans judge intent is most definitely important, especially given the robust nature of these results. This study found no statistical significance in the language variables we tested, however, there is no certainty that this study tested for all language variables.

6. FUTURE WORK.

There has been some discussion as to the involvement of the terms help and harm in this phenomenon. A question has been raised about an entailment of intention within these terms (Scientopia 2010). A semantic explication and use of corpora may return some interesting results. Also a cross-linguistic analysis may also have interesting returns; perhaps a language other than English would not carry the same semantic packaging and therefore would yield different results. Any of these could either provide more understanding into the mechanist of this phenomenon or provide a wider base of empirical support of the effect.

More work is being done by Joshua Knobe and his colleagues to better understand the mechanism of this and similar phenomena. They have used a variety of variables and redefined, in many ways, the disciplines of cognitive science and philosophy of mind. This work is also of significant interest to many other disciplines, linguistics being only one. Neuroscientists and Psychologists also have a role to play in this research. The variety of approaches brought by diverse disciplines can provide much more insight into the cause of this asymmetry.

REFERENCES

- BORODITSKY, LERA. 2011. How Language Shapes Thought. Scientific American 304.2: 62-65.

- DAVIES, MARK. 2008-. The Corpus of Contemporary American English: 450 million words, 1990-present. Available online at http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/.

- KNOBE, JOSHUA. 2003. Intentional Action and Side-Effects in Ordinary Language. Analysis 63:190-193

- KNOBE, JOSHUA. 2003. Intentional Action in Folk Psychology: An Experimental Investigation. Philosophical Psychology 16:309- 324.

- KNOBE, JOSHUA. 2004. Intention, Intentional Action and Moral Considerations. Analysis 64:181-187.

- KNOBE, JOSHUA. 2006. The Concept of Intentional Action: A Case Study in the Uses of Folk Psychology. Philosophical Studies. 130:203- 231

- LOFTUS, EF; PALMER JC. 1974. Reconstruction of Automobile Destruction: An Example of the Interaction Between Language and Memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 13: 585–9.

- SCIENTOPIA. 2010. The Knobe Effect. http://scientopia.org/blogs/childsplay/2010/10/14/knobeeffect. Accessed Oct 2011.

- THIBODEAU PH, BORODITSKY L. 2011. Metaphors We Think With: The Role of Metaphor in Reasoning. PLoS ONE 6(2): e16782.