Matthew Frei and Dr. J. Quin Monson, Political Science

Some political science and sociology scholars distinguish between two dimensions of religiosity or religious commitment: individualism and communitarianism. The former means that individuals are motivated toward piety with an emphasis on an intrinsic or individual-level religious practice and belief (Allport and Ross 1967). The communitarian perspective, by contrast, claims that religiosity is driven by communal experience, with an emphasis on religion’s social and group-based rituals. Political scientists regularly measure religiosity with an almost exclusive focus on individualistic beliefs and behaviors such as whether the individual survey respondent believes in God, attends church, or believes the Bible to be the word of God. A recent paper by Mocakbee, Wald and Leege argues that those traditional measures fail to capture the communitarian dimension of religiosity.

Those scholars found evidence that many national public opinion surveys have misunderstood the effect of religious devotion on partisan identification because the survey questions focus only on the traditionally individualistic measures of religiosity. By introducing a measure of communitarian religiosity, they found that communitarian Christians who consider trying to “help other people” more important than trying to “avoid doing sinful things yourself” lean more to the ideological left. One shortcoming of this early research on communitarian religiosity is that not enough thorough measures of religious communitarianism have been developed to fully explore the relationship between communitarian religiosity and political attitudes and behavior. The goal of my research project was to more fully develop a battery of survey questions capable of quantifying communitarian religiosity. Accomplishing that goal would help scholars and students of American Politics better understand the role of religious beliefs in the political sphere.

Using an original survey of 550 Utah voters drawn from the BYU Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy’s Utah Voter Poll panel, I piloted a series of new questions that intended to measure the strength and communitarian nature of respondents’ religious attachments. The survey was administered online from February 27 to March 12, 2012.

In their national ANES survey in 2008, Mockabee and his colleagues found that 52% of Christians think it is more important to help other people than to avoid sin themselves. To understand whether my Utah sample differs significantly from the national Christian population, I began by replicating this original question. In my survey, 78% of Utah voters chose the second option. The larger number of communitarian Christians in Utah indicated that the Utah sample might be an especially good place to study communitarian religiosity.

But, before attempting to developed a battery of question for measuring communitarian religion, I thought it important to first replicate Mockabee’s finding that respondents who think it is more important to serve others lean more toward the Democratic party. A simple cross tab shows that 74% of Utah’s Christian Democrats are communitarians while only 86% of Christian Republicans in the state are the same. The difference is statistically significant at the .05 level. These findings largely parallel those at the national level. Of course, it is possible that these findings are attributable to other variables correlated with both communitarian religiosity and party identification. To identify whether communitarian religiosity has an independent effect on party identification, I estimated a regression model to control for religious affiliation, age, income, education, and gender. Even in the presence of these control variables, the effect persists.

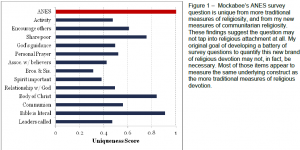

Once I had replicated Mockabee’s basic findings using my survey of Utah voters, I turned to developing a more comprehensive measure of religiosity. I designed six new questions to measure communitarian religiosity including questions about the importance of association with church members. I also used six traditional survey measures of individualistic religiosity for comparison. One such question asked about the respondents’ about the importance of a personal relationship with God in their lives. To explore whether the 12 questions actually tap into two separate (individualistic and communitarian) dimensions of religiosity, I conducted a factor analysis. To my surprise, the measures did not separate into two factors. Instead, there was only one major factor. Figure 1 shows the uniqueness scores produced by the factor analysis. The higher the uniqueness scores for each item, the less they measure the same underlying construct as the other questions. Interestingly, Mockabee’s original question is the most unique of all the items. This evidence leads me to conclude that Mockabee’s original question may not measure religiosity at all. Although people who think that it is more important to help other people are, all else being equal, more likely to be Democrats, this effect may not stem from religious devotion. Using this evidence, I presented a poster at the 2012 BYU Fulton Mentored Student Research Conference arguing that, contrary to my original supposition, a battery of questions measuring religious communitarianism may be unnecessary.

REFERENCES

- Mockabee, Stephen T., Kenneth D. Wald, and Devid C. Leege. 2009. ―Is There a Religious Left?: Evidence from the 2006 and 2008 ANES.‖ Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Toronto.