Devaun Sheppard and Dr. Barbara Mandleco, Nursing

The purpose of this quantitative descriptive study was to examine caregiver burden and family hardiness in families raising children with disabilities (CWD) to determine 1) If there are differences in these variables according to parent gender and type of disability, and 2) If there is a relationship between the variables so more appropriate interventions can be provided to these families.

Research has shown the responsibilities of giving care to a CWD add a significant amount of stress to caregivers and their families (Kazak & Marvin 1984). Caregiver burden is a way to describe the effects of this stress on caregiver. Although there is evidence of increased stress and caregiver burden in families raising CWD, a high level of stress/caregiver burden does not necessarily lead to dysfunction; many families raising CWD are able to adequately adapt and adjust to the event (Kazak & Marvin 1984). One possible explanation for family adaptation to the stresses of raising a CWD might be their hardiness. Hardiness, the common trait found in people who resist illness during stressful life events (Kobasa, Maddi, Kahn 1982), has three characteristics: control, commitment, and challenge. Specifically, family hardiness is exemplified by the view of change as an opportunity for growth and an active orientation in adjusting to and managing stressful situations. There is little information in the literature discussing the link between caregiver burden and hardiness and examining whether perceptions of family hardiness vary according to parent gender or type of disability.

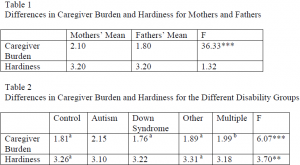

The study included 209 parents of CWD. There were five different groups of CWD—control, autism, Down syndrome, other disabilities, and multiple disabilities. Other disabilities included developmental delay, emotional disability, hearing impairment, communication disorder, speech delay, and ADHD. The multiple disability group included disabilities that involved both cognitive and physical limitations. These disabilities included Traumatic brain injury, FG syndrome, Trisomy 13, Trisomy 22, and other genetic disorders. Participants completed the 20 item Family Hardiness Index (McCubbin, McCubbin, & Thompson 1991), and a revised version of the Caregiver Strain Index (Robinson 1983). Analysis revealed mothers rated caregiver burden between sometimes and a lot whereas fathers rated caregiver burden between rarely and sometimes (m = 2.10; f = 1.80). The mean hardiness score for both parents was 3.20, which suggests parents were fairly hardy. Mothers scored significantly higher on caregiver burden than fathers, but there was no difference between genders when rating hardiness (see table 1). However, parents of children with autism scored significantly higher in frequency of caregiver burden and significantly lower in hardiness than parents of children with Down syndrome, other disabilities, and multiple disabilities (see table 2). There was a negative correlation between frequency of caregiver burden and family hardiness (r=-.40, p<.001).

These findings are not uncommon according to current literature. Many studies have found that mothers have higher daily parenting stress, feel more pressure to balance caregiving and household duties, and report poorer health and lower sense of coherence in their family (Gerstein et al 2009; Oelofsen & Richardson 2006). Other research has studied how parents of children with autism perceive their children have low social skills and high problem behaviors (Griffith, Hasting, Nash & Hill 2009).

The implications of these results focus on individualizing support for mothers of CWD and parents of children with autism by increasing family hardiness and lowering caregiver burden. It is important for professional staff to understand that not all families of CWD are the same, and each mother and parent of a child with autism needs targeted psychological and emotional help (Hockenberry & Wilson 2011). This study concretely explores these weaknesses of such families and then proves how to strengthen those weaknesses. Finally, this study provides strong coping mechanisms through emphasizing the importance of strengthening family hardiness and lowering caregiver burden.

References

- Gerstein, E. D., Crnic, K. A., Blacher, J., Baker, B. L. (2009). Resilience and the course of daily parenting stress in families of young children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53(12), 981-997.

- Griffith, G. M., Hasting, R. P., Nash, S., & Hill, C. (2009). Using matched groups to explore child behavior problems and maternal well-being in children with down syndrome and autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 610-619.

- Hockenberry, M.J., Wilson, D. (2011). Wong’s nursing care of infants and children. Saint Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby.

- Kazak, A., & Marvin, R. (1984). Differences, difficulties and adaptation: Stress and social networks in families with a handicapped child. Family Relations, 33, 67-77.

- Kobasa, S. C., Maddi, S. R., & Kahn, S. (1982). Hardiness and health: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 168-177.

- McCubbin, M. A., McCubbin, H. I., & Thompson, A. I. (1991). FHI Family Hardiness index. In H. I. McCubbin & A. I. Thompson (Eds.), Family assessment inventories for research and practice (pp. 127-136). Madison: University of Wisconsin.

- Robinson, B. C. (1983). Validation of a caregiver strain index. Journal of Gerontology, 38(3), 344-348.