Nicholas Jones and Dr. Darren Hawkins, Department of Political Science

Our research examines whether donor countries care about the quality of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) when giving foreign aid to poor countries. When donor states give foreign aid to recipient states, such the US giving foreign aid to Uganda, the donor states must choose what is called a channel of delivery. This is the channel through which the donor’s aid will reach the intended beneficiaries. Donors can opt to channel their aid directly through the recipient government, or they can sidestep the recipient government, and instead utilize a non-state channel such as an NGO or multilateral organization. Presumably, donors will normally elect to channel their aid directly through the recipient government, because much of the purpose of aid is to help the government better meet the needs of its people.

Many donors, though, have become frustrated of late with corruption in recipient governments, which results in either their aid money being mismanaged, or perhaps even captured by the government, and spent on things unrelated to aid. Because of this, donor states have increasingly circumvented recipient governments and instead utilized non-state channels, such as NGOs in their aid allocation decisions. Donors states often see NGOs as an appealing alternative to governments (their very name reflects this; they are defined by what they are not), because they ostensibly are free from much of the corruption that plagues governments in developing countries. Thus, NGOs perhaps present an avenue where donor’s aid is more likely to be well used. However, partially in response to this, some recipient governments see NGOs as a threat and as such, impose crippling regulations on them or arbitrarily dissolve them. Furthermore, many NGOs lack sustainable sources of funding, are not effectively managed, or are in fact corrupt themselves. Since not all countries have NGOs with equal capacity to carry out aid projects, donors should take this into consideration when making decisions about how to channel their aid, so that it can be most effectively used to alleviate suffering and stimulate economic growth.

In our research we define NGO capacity as the ability of NGOs to formulate and implement their missions. We quantify this variable and use it in our model of donor’s channel of delivery decisions. We hypothesize that donors will channel choose non-state channels in poorly-governed recipients, and that they will choose NGOs more often in recipients with high NGO Capacity.

To quantify NGO capacity, we use the NGO Sustainability Index (NGOSI) published by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The index contains factors such as the legal environment NGOs face, the sustainability of their funding, and the extent to which the public trusts them in that country. The NGOSI is published for the years 1998-2009 for the Eastern Europe/Eurasia region, and in 2009 only for the Africa region.

To quantify recipient governance, we use the Government Effectiveness indicator from the World Governance Indicators, published annually by the World Bank. We also include other control variables such as recipient income, whether the recipient was a former colony of a donor, whether there was a civil war in the recipient, etc.

In order to operationalize the channel of delivery that donors choose, we create a binary variable called bypass. The variable is coded as a 1 if a donor channeled less than 0.5% of their aid through the recipient government in that year, and 0 as otherwise. Operationalizing channel of delivery in this way allows for donors to still fund token projects through the recipient government, so as not to incur their complete anger, while still effectively bypassing them.

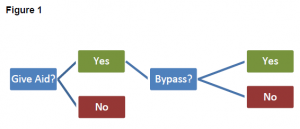

It is important to note that our dataset contains non-randomly missing data, because we only have data for aid projects that donors decided to fund. If Germany chose to give aid to Morocco in 2004, we have that data, but if they decided not to give aid to Mozambique in 2004, that would-be aid project is clearly absent from our dataset. Therefore, the presence or absence of an aid project in our data is related to a prior decision on the part of the donor. This can introduce what is called selection bias into our model, corrupting the estimates of how much NGO capacity affects donors’ decisions. To account for these selection effects, we employ a two-stage sample selection model. The first stage looks at what factors influence whether or not a given recipient received aid from a given donor in a certain year. The next stage of the model looks at what factors influence whether a given donor bypasses the government of a certain recipient, and instead opts to channel virtually all of their aid through and NGO or multilateral organization. Figure 1 illustrates this model.

We find little evidence that donors take NGO capacity into account when making aid allocation and channel of delivery decisions. In Eastern Europe and Eurasia, NGO capacity has no statistically significant effect on whether donors bypass the recipient government or not. In Africa, surprisingly, donors utilize NGOs significantly more often in the recipients that have the lowest NGO capacity, and utilize NGOs significantly less often in the recipients with the worst NGO capacity. At first we thought that his was because well-governed countries will likely have higher-capacity NGOs, in which case the donor state would simply opt to utilize the well-governed country. However, these results stand even after controlling for governance, so the capacity of the recipient state is not driving them. It appears that donors are either not cognizant of NGO capacity, or that it is proxying for some other unobserved variable which influences channel of delivery decisions on the part of donors.