Victoria Garcia and Dr. Kirk Hawkins, Department of Political Science

Populism is “a Manichaean discourse that identifies Good with a unified will of the people and Evil with a conspiring elite” (Hawkins 2009). It is a movement that has been spreading in Latin America, in which a group of people consider themselves as the majority being oppressed by an Evil elite. The surge of charismatic leaders seeking to represent the will of the people characterizes this movement. An example of these types of leaders is Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, where he is supported by a populist majority.

Studies on the correlation between religion and populist movements within the United States have shown that specific religious denominations, such as Evangelical denominations have influenced a surge of Populism throughout the country (Wald 2007). My research intended to find a relationship between the religious denomination and the individual level of religious conviction and their relationship with Populism in the Latin American region. In order to do this, I analyzed data from the Americas Barometer, a public opinion survey done in 18 Latin American countries with a comprehensive range of questions. This dataset contains information about an individual’s religious practices and populist tendencies. The surveys contained seven questions that measured an individual’s populist tendencies and two questions that indicated their religious affiliation and level of commitment to that affiliation. Additionally, to determine the control variables needed for the statistical analysis, such as gender, income, age, level of education, and ideology, I used the comprehensive range of questions included in the Americas Barometer survey.

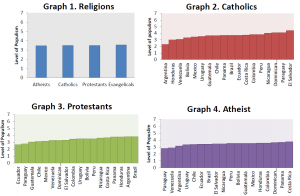

Using all of this data, I created a dataset in a statistical program called STATA which allowed me to perform a multivariable regression. In this dataset, I included only the question indicating religious affiliation because all of the religions displayed similar levels of commitment. Additionally, the seven questions measuring populist tendencies were combined into a single index, on a scale from 0 to 7, being 7 the highest level of Populism. The regression allowed me to see how the religion variable affected the level of Populism of the people in a specific religion within a country. First, I compared the religions without controlling for nationality. In this regression, the relationship of religion and Populism is not significant. This suggests that the basic beliefs of a religion do not have an effect on the level of Populism. See Graph 1.

After the first regression, I compared all the religions for each specific Latin American country. Some religions were dropped in this regression due to the small amounts of observations in them that might have skewed the results. These religions were the Mormons/Jehovah Witnesses, Esoteric religions, and Non-Christian religions. Atheism was considered a religion because it constitutes a significant group of adherents within the countries who share a common belief. This second regression showed that some religions are more populists in some countries than in others. Some denominations were statistically significant being either more or less populist than the rest of the religions. Given the socio-demographic controls included in the model, this suggests that national organizations have an independent effect on an individual’s political attitude. See graphs 2, 3, and 4.

The results show that unlike United States, where beliefs play the most significant role in determining a person’s degree of Populist support, Populism in Latin America is determined by the local religious group or organization to which people belong. It is not the beliefs of the people’s religion in the region that make them populists, but the specific characteristics of each religious group in each Latin American country that make them more or less populists. According to the definition of Populism, this might be explained by the idea that people in a certain group identify themselves as “the people” or as a majority, considering the rest as the “conspiring elite” who is trying to oppress them. Many of these national religious groups may consider themselves as “the people” being oppressed, making them more supportive of Populism. This research found that the relationship between Populism and religion in Latin America is different to that in United States, but further research needs to be done in order to understand what makes some groups more populists in each Latin American country. These results were presented at the Mary Lou Fulton Mentored Research Conference.

References

- Hawkins, Kirk A. “Is Chavez Populist?: Measuring Populist Discourse in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Political Studies, 2009: 1040-1067.

- Wald, Kenneth D, and Allison Calhoun-Brown. Religion and Politics in the United States. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007.