Bryce Bristow and Dr. Shawn Nissen, Department of Communication Disorders

I was able to present the following research at the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association 2012 National Conference. I made a poster and talked to professionals and researchers from across the nation.

Introduction

It is hoped that by increasing our understanding of gender differences in the ability to produce prosodic aspects of speech, clinicians will be able to more accurately assess and effectively treat communication disorders. To this end, this projected aimed to describe the acoustic parameters of contrastive stress production, looking especially at any differences in production between males and females. Constrastive stress is the emphasis put on words to indicate information that is different or new. For example, if the question “Is the sky green?” were asked, the reply would likely be, “No, the sky is blue!” The emphasis on “blue” is contrastive stress.

Methods

All participants were adults between the ages of 20 and 28. None had any history of serious speech, language, or hearing problems. Participants were presented with simple line-sketch pictures and prompted to repeat the baseline sentence (e.g. “The lady is picking the flower”). After the baseline, questions were asked (e.g. “The man is picking the flower?”) to elicit contrastive stress in both subject and verb positions. Each participant was presented with 5 trials of pictures. The recordings were analyzed using Praat software. The maximum F0 frequency and intensity of the stressed word were gathered, as well as the mean F0 freqency and intensity of the entire utterance. Intensity was measured in decibels, and frequency was measured in hertz. Because of the difference in pitches between men and women, the F0 frequencies were normalized by converting to semitones.

For the statistical analysis, I used a two-factor ANOVA with repeated measures on the data to determine significant differences between males and females.

Results

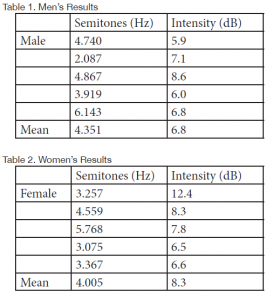

The results in Table 1 and Table 2 are the mean semitone and decibel levels among the five trials.

The ANOVA had a p < 0.05 for the comparison between men’s and women’s use of tone and intensity.

Conclusions

Although the data shows a statistical difference between male and female speakers, these findings should be considered preliminary because, in part, of the small sample size. It is interesting to note that the data show that men are more likely to use frequency to signal contrastive stress than women. This seems to run contrary to the literature, which has shown that women in general use more frequency modulation in conversation. However, this data can be considered congruent with past experience. Because women modulate their tone more in conversational dialog, using frequency to signal contrastive stress would be less effective, as it could be mistaken for normal variance. Men, on the other hand, have a relatively flat conversational tone curve, so smaller variances could lead to more clear production of contrastive stress.

Of course, even though the differences are statistically significant, the actual difference isn’t practically significant.

As well, over the course of the gather the research, some procedural methods were discovered that could help make the data collection more consistent and natural for participants. The two main improvements are as follow:

- Since little difference was discovered in the production of contrastive stress between the subject and verb positions, researchers should only ask for one response per picture. This would mitigate the repetitive nature of the task, providing more natural utterances.

- To reduce undue influence by the researcher, participants should not explicitly be given an example of contrastive stress, lest the researcher’s prosodic patterns be unconsciously mimicked.

It is highly recommended that this project be expanded and that it incorporate the above recommendations. With a larger population size, and better research methods, a more significant finding could be found.