Matthew Butler and Dr. Eric Eide, Economics

Most economists contend that racial discrimination cannot exist in a “free” labor market because competition will drive any firm that discriminates to bankruptcy. This contention is presented, perhaps most famously, in Gary Becker’s book the “Economics of Discrimination.” The question of whether Becker, and all economists, knows best is relevant because if “free” labor markets do work towards eliminating discrimination, the policy implications are for the government to take a laissez-faire stance towards regulating discrimination-to step back, and to simply allow the market to correct itself. The NBA provides a natural experiment to test whether or not “free” labor markets, or institutional changes towards a more “free” labor market, can help eliminate racial discrimination.

The institutional changes that provide a natural experiment occurred in the second half of the 1980s. In the summer of 1987, the NBA players’ union won a collective bargaining agreement that included two crucial institutional changes. The first was unrestricted free agency. Before the new collective bargaining agreement, players were not able to sell their skills freely on the NBA labor market. Their teams had the right to match any offer made by another team and automatically retain the player’s services regardless of his wishes. Unrestricted free agency created a labor market where competition could play a greater role because the player’s former team no longer enjoyed any bargaining advantages over other competing firms. The second collective bargaining agreement change was the “Larry Bird clause” which allowed teams to surpass salary cap restrictions to resign their own players who had become free agents. This allowed teams to offer players their true market value by surpassing the artificial ceiling imposed by the team salary cap.

The second institutional change occurred within a year of the collective bargaining agreement when the NBA awarded expansion franchises to four cities. The additional franchises expanded the number of firms bidding for the players’ services. Additional firms create a more competitive market environment where firms are forced to pay any given player their true value regardless of their race.

Current economic research tends to support the hypothesis that institutional changes helped eliminate discrimination. Studies done before the changes, almost categorically, found racial discrimination against blacks. However, more recent studies have found no statistically significant discrimination. I will attempt to provide a more rigorous test to examine whether these institutional changes helped eliminate discrimination.

I used an OLS regression with several racial interaction terms. The data for this analysis was taken from Zander Hollander’s “The Complete Guide to Pro Basketball.” It spans 1987-1996-except for 1992-and contains 2,025 observations. The set includes performance characteristics, and dummy variables for race, year, and other categorical variables. I employed the traditional log-linear transformation of salary on the variables of interest to estimate how black players’ earnings profiles changed over time. The hypothesis was that black players would experience a salary boost after the more “free” labor market institutional changes were implemented. To simulate this change over time I interacted dummy variable for race with each year in the data set. If the hypothesis was correct, then the year following these changes blacks should experience a higher increase than whites in salary. After finding heteroskedasticity in the data, I corrected for it using a heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix.

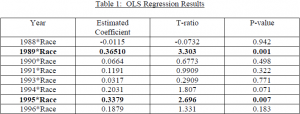

In the following table I report the results of the racial dummy variable interacted with each year in the data set. 1987 provides the base year of reference. Because of the log-linear transformation, the estimated coefficient represents the percentage salary increase that black players experienced in that given year relative to white players.

The results of the regression support the anti-discriminatory effects of free labor markets but not conclusively. The year 1989 represents a statistically significant 36.5% increase for blacks relative to whites. However, 1989 represents a two year lag in the market’s corrections. We can conclude that shortly before 1989 some stimulus worked to eliminate discrimination but not necessarily that it was the institutional changes I’ve mentioned. Though not conclusive, the results do provide more rigorous support for the intuitively appealing conclusion that these institutional changes created a more “free” labor market.

Blacks also experienced positive gains in 1994 (though not statistically significant) and 1995. This was an unexpected result of the analysis. Upon further inspection, 1994 and 1995 represent another round of collective bargaining. The correlation between collective bargaining between an increasingly black players’ union and franchise owners is apparent on a surface level.

Questions remain. How can a more definitive relationship be drawn between labor market institutional change and racial discrimination? If it can be done, which institutional change had the greatest impact? Intuitively, the expansion teams had less of an impact because of the relatively small percentage change in franchises they brought. Unrestricted free agency and the “Larry Bird clause” were probably the factors that reduced racial discrimination in the NBA. The difficulty will be to differentiate between the effects.

Ultimately the test is whether “free” labor markets work to eliminate discrimination. This analysis suggests a direction towards providing an empirical test of that theory. My results only that it is more likely than not that Becker knows best. The results supports Becker’s view-but far from conclusively.