Michele N Richardson and Dr. Samuel Otterstrom, Geography

Introduction

At the end of World War I, the Treaty of Trianon divided the former Austro-Hungarian Empire into multiple autonomous states including Czechoslovakia. Hungarians vociferously decried the southern border around the Slovak portion of this state, which became the independent Slovak Republic in 1993, claiming that it bisected an ethnically homogeneous Hungarian area between two political states. Conversely, proponents of the 1918 border argued that the dominant Hungarian presence in southern Slovakia was merely the result of Magyarization, a government policy aimed at suppressing minorities and forcefully assimilating them into Magyar (ethnic Hungarian) culture. Unfortunately, at this time nobody definitively knew where various ethnic groups in southern Slovakia resided prior to the implementation of Magyarization in the nineteenth century. Thus no conclusions could then be reached concerning the effects of Magyarization upon Slovakia’s ethnic demography.

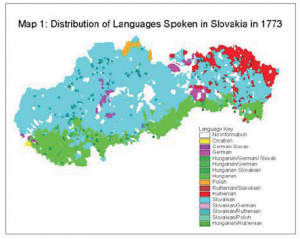

In 1920, the Delegation of Peace of Hungary published the 1773 Lexicon universorum Regni Hungariae locorum populosorum etc. in support of their claim that Hungarians had never forcefully spread their language but only ever attempted to spread western culture throughout the area, including Slovakia, that they controlled (Hungary 1920, v). The delegation also asserted that this 1773 lexicon was completely objective as it was compiled in Vienna prior to the nationalism movements and resulting anti-nationalism government policies, such as Magyarization, of the nineteenth century (Hungary 1920, vii). Alone, this 1773 lexicon has been unable to clearly reveal Slovakia’s ethnic demography prior to the nineteenth century because it exists only in table form.

Objectives

I therefore had three objectives for this project: to map the 1773 lexicon’s ethnic data, to compare the 1773 data with 1910 census data, and to comment on my findings’ implications for the debate concerning whether or not the post-nineteenth century Hungarian presence in southern Slovakia was the result of Magyarization.

Though I also mapped the distribution of church buildings throughout Slovakia in 1773, I was unable to compare this data with the ethnic data due to time constraints. Such analysis does, however, provide an opportunity for further study.

Limitations

Not only is the determination of ethnicity highly subjective, but while ethnic groups usually share any combination of historical, racial, territorial, cultural, and linguistic similarities, there are also no essential characteristics common to all ethnic groups (de Vos and Rimanucci-Ross 1982, 9). However, language was the only one of the above ethnic indicators that was reported on the 1773 lexicon and was thus used as the sole ethnic indicator for this project.

The most significant limitation encountered in this project, however, was the fact that the 1773 lexicon only reported the language spoken by a commune’s majority, and failed to indicate how large this majority was. Occasionally, the 1773 lexicon listed multiple languages for one commune, but there was no indication whether or not these languages were spoken by equal percentages of a population or indicate a hybrid dialect. Therefore, the only change that this project can comment on is that of ethnic majorities.

Process

The country of Slovakia is divided into nineteen counties sub-divided into a number of districts. Each district is further divided into communes. To accomplish this project’s objectives, I matched the approximately 3,196 communes on the 1773 lexicon with their counterparts on a 1910 map previously digitized by my advisor, Dr. Otterstrom. I then used identification numbers assigned to each commune to link each commune’s linguistic characteristic with its location on the digitized map. Despite the fact that the 1773 lexicon usually listed Latin, Hungarian, Slovakian, and German translations of commune names, the use of a translation database, provided by my advisor, was imperative in clarifying myriad instances in which commune’s developed, combined, split, or disappeared entirely between 1773 and 1910.

Results

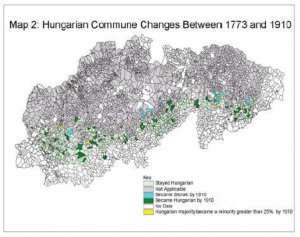

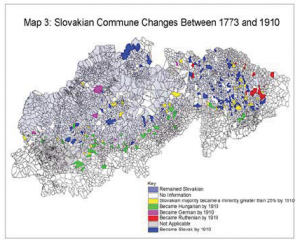

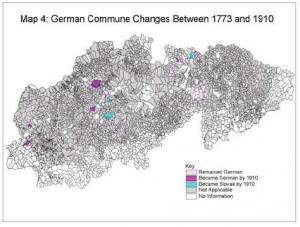

As Maps 2, 3, and 4 reveal, the ethnic boundaries in the area of modern-day Slovakia remained largely unaltered between 1773 and 1910. Most of the changes that did occur, however, did so in the direction of consolidation. For example, most Slovak-dominated communes that had become Hungarian-dominated by 1910 are found within larger areas dominated by Hungarians in both 1773 as well as in 1910 (see Map 3). There are, however, numerous exceptions; the most notable of which are changes in German-dominated communes that are generally found in small clusters throughout eastern Slovakia (see Map 4). All exceptions from the consolidation trend, however, provide opportunities for additional research.

Discussion

While the consolidation trend directly refutes assertions that Magyarization was effective in the widespread assimilation of non-Magyars into Magyar culture, it remains possible that Magyarization was responsible for an increase in minority Hungarian populations. Unfortunately, minority data was not reported on the 1773 lexicon and thus, no conclusion on this subject can be reached at this time. However, as the maps I created reveal, a significant Hungarian presence already existed in southern Slovakia in 1773, prior to the implementation of Magyarization in the nineteenth century. Thus it can be concluded that Magyariation was not responsible for the strong 1910 presence of Hungarians in southern Slovakia.

It is also significant to note the striking similarities between the topographical map (see Map 5) and the maps produced by this project (see Map 1). While Slovak-dominated populations are found in the northern mountainous regions of Slovakia, Hungarian-dominated populations are found in southern Slovakia along the riverbeds and other low elevation areas topographically inclined to be agriculturally productive (Otterstrom 2000, 141). In fact, in 1991, areas with high Hungarian percentages corresponded with high agricultural employment while areas with high Slovak percentages corresponded with high industrial employment (Otterstrom 2000, 146). In combination with the maps that I created, these findings suggest the theory of ‘ecological 367 niches,’ that the Hungarian presence in Slovakia was primarily based upon the area’s topography (Hannan 1979).

Bibliography

- De Vos, George and Lola Romanucci-Ross, ed. 1982. Ethnic Identity: Cultural Continuities and Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hannan M.T. 1979. The dynamics of ethnic boundaries in modern states. Edited by J. W. Meyer and H. T.

- Hannan. National development and the world System: Educational, economic, and political change 1950-1970. 253-275. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cited by Samuel M. Otterstrom in “Ethnic and economic regions in Slovakia: A statistical and visual exploration of contemporary patterns.” GeoJournal 52 (2000): 139- 147.

- Hungary. Delegation of Peace of Hungary. 1920. Topographical lexicon of the communities of Hungary compiled officially in 1773.

- Otterstrom, Samuel M. “Ethnic and economic regions in Slovakia: A statistical and visual exploration of contemporary patterns.” GeoJournal 52 (2000): 139-147.

|

|

|

|