Elisa Zavala and Dr. Steve Bule, Humanities

Dynamism, vibrance, movement and sumptuous color all define the art of the Southern Baroque period. Throughout my study of Art History this period has been the focus of my interest, therefore the opportunity to travel about Italy and Spain was a prime experience to delve deeper into the works and life histories of the artists of the Southern Baroque. I found that simply being surrounded by the environment and the people that influenced the artists of this era took me to a different level of understanding. My main subject of study while in Italy was the artist Artemesia Gentileschi. The paintings of Gentileschi embody the Baroque for they display a richness of color, texture, and movement. Nevertheless the visual qualities of Gentileschi’s paintings are not the only factors that drew me to her. The life of this artist, especially her life as publicized by feminists, is one that equals the tumult and violence of her paintings.

In the 1970’s Artemesia was brought into the limelight and identified as a proto-feminist. Her paintings of the Apocryphal stories of Judith and Halofernes and Susanna and the Elders were used as examples of her resistance and aggression towards a male-dominated seventeenth century society that had abused her. A factor that strengthened the theory of Artemesia as a feminist is that at the age of sixteen her father accused one of his apprentices of repeatedly raping her. As a result a lengthy court trial ensued in which Artemesia endured a public gynecological exam and torture by thumbscrew. Agostino Tassi, the apprentice, recieved a prison sentence of six months.

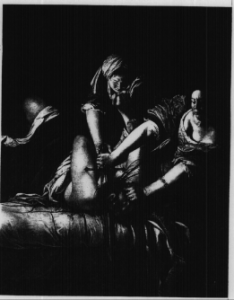

After the trial Artemesia moved from Rome to Florence, married and had two daughters. She continued to paint and made a successful living from her works. She followed the style of Caravaggio who heavily incorporated the use of chiaroscuro, or the use of shadows and light to create contrast and drama. Also like Caravaggio Artemesia’s works did not hide violence, in fact she mingled violence with other qualities like sexuality. This is most apparent in her versions of Judith and Halofemes which is housed in the Uffizi gallery in Florence and Susanna and the Elders. She does not hesitate to depict the fatal and gory moment when Judith beheads the General Halofernes who would have conquered her people if she had not taken action. Artemesia’s portrayal of Judith is strong, resolute, and determined.

We see that the image of Artemesia as a feminist in her own time is facilitated by her life history and her choice of subjects. My proposal was to research the period of the Baroque by subject and style and to compare the work that Artemesia was doing to the works of her male contemporaries. My hypothesis was that her works were not so unordinary when it came to subject and style and that indeed they fit the period, but the fact that she was a woman made her a prime candidate to fill a political agenda for feminism. As a result she became recognized for her gender and was overlooked for her talent as an artist. When in Italy I had the opportunity to see just how popular the theme of Judith and Halofemes was both in the Renaissance and in the Baroque period of Italy. The image of Judith decapitating Halofemes is present in prominent stations of cities such as the Piazza Signoria in Florence where it stands next to a replica of Michelangelo’s David. In Rome the image takes its place on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. It is also included on frescoed ceilings throughout many of the cathedrals that we were able to study. The context of the representation of Judith and Halofemes is vital. In Florence Judith was chosen as a symbol of their Republic combating their enemies. Judith represents the victory of a small but forceful figure over a luxurious and barbaric giant. Alternately, she is a long-standing symbol of virtue. This virtue would protect the people against any form of tyranny. For the Swabian League of cities Judith was the protective patroness. In a more abstract sense Judith could symbolize the triumph of chastity and virtue over the sins of gluttony and hubris—these being represented by Halofemes. Several of these themes are possible influences for Artemesia’s having chosen to depict this singular event.

When viewing the paintings of Artemesia in Italy I found that they did fit the style, subject and theme of the Baroque period in which she lived. In fact while viewing her work and those of her male counterparts the genders of the artists were impossible to tell. The revival of recognition of Artemesia Gentileschi’s works was a much needed one, not because she was female but because her skill was superb. Her work does not require a political agenda such as feminism in order to establish importance — it does so very well on it own.