Dagan Pielstick and Francesca Lawson, Comparative Arts & Letters

Introduction

The relationship between speech and song has been an area of interest in evolutionary biology and neuroscience over the past two decades. Some evolutionary biologists have hypothesized that music and language descended from a protolanguage in early human communication (Brown 2000). At the same time, developments in technology have made it possible to analyze the activation of different parts of the brain, allowing us to see traces of this evolutionary history in the neural pathways of the brain (Patel 2008). Recent studies on language-music relationships both support and contradict the theory of a common protolanguage base for music and language (see Schon 2010, Peretz 1994, and Orellana 2014). Using fMRI scans, we can measure the neural activity and see if the same or different pathways are used for speech and song.

Methodology

For stimuli, “Oh Shenandoah” and “I Need Thee Every Hour” we selected for their musical similarity and familiarity with the subjects. These pieces were recorded spoken and sung by a female vocalist. 15 students who were right handed, had no professional or collegiate musical training, and did not self-identify as ‘tone deaf’ (to ensure they had the ability to process music) were selected. Students with professional music training were excluded as the differences between spoken and sung language are less pronounced with a strong music background, as noted by Anglo-Perkins (2014). Students were scanned onsite at BYU using our fMRI machine. While in the machine, the participants head alternating blocks of spoken and sung stimuli.

Results

Spoken versus Sung

To examine the overall difference between spoken and sung lyrics, we contrasted spoken versus sung lyrics. We saw no significant activation differences between the spoken and sung stimuli.

Religious versus Non-religious

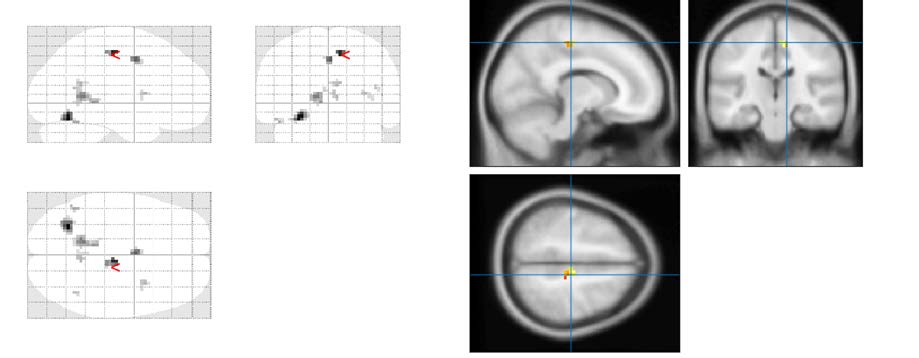

Examining the religious effects of the study, we contrasted the religious versus the nonreligious stimuli. This comparison yielded several regions of interests (ROI). We observed increased activation (p-value < 0.05) in the right middle temporal gyrus and the posterior cingulate gyrus (see Figure 1: Sung blocks contrasting religious versus non-religious stimuli). This activation suggests religious lyrics evoke a stronger emotional reaction than non-religious lyrics.

Spoken Stimuli Contrast

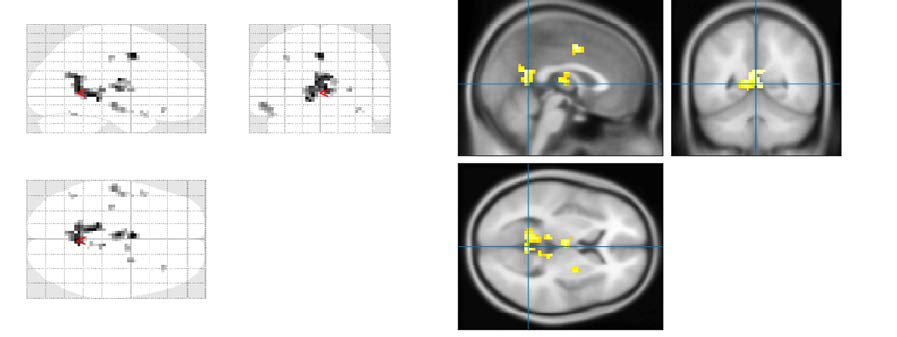

Isolating the analysis of religious versus non-religious stimuli to just to the spoken data, we found several ROIs. Figure 2shows increased activation (p-value < 0.05) in the right middle temporal gyrus, as is expected in spoken language, as well as activation at the boundary between the left inferior portion of the superior temporal gyrus and the left superior portion of the middle temporal gyrus (adjacent to the left temporal sulcus). This suggests responsiveness to multi-sensory integration rather than to spoken language alone. This might indicate that the auditory perception of spoken song lyrics is different than the auditory perception of words without the attachment to song.

Spoken Stimuli Contrast

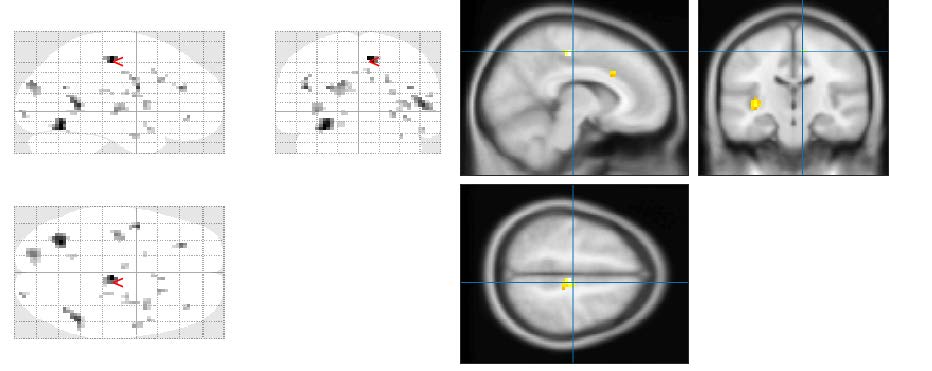

Isolating the religious versus non-religious contrast to the sung stimuli, we found increased activation (p-value <0.05) in the posterior cingulate gyrus, see Figure 3. This suggests a greater emotional response to religious song than to non-religious song.

Discussion

Finding no significant activation differences between spoken and sung song lyrics suggests that the neural pathways in processing the lyrics had significant overlap. Otherwise there would be more pronounced difference in the neurological processing of these different stimuli. Contrasting the religious versus non-religious stimuli on the spoken lyrics, the increased activation we found indicates that the subjects had a multisensory experience. This suggests that the auditory perception of spoken lyrics is different than that of spoken language alone. We also saw an increase that suggests an increased emotional response to religious stimuli. While exploring the neurological process of speech and song, we saw evidence that the neural pathways overlap (hence no significant activation differences between spoken and sung language) and that the religious stimuli result in a stronger emotional response from the subjects.

Figure 1 – Religious contrasted with the non-religious stimuli. We can see increased activation in the right middle temporal gyrus and the posterior cingulate gyrus, suggesting a stronger emotional response.

Figure 2 – Spoken blocks contrasting religious versus non-religious stimuli. We can see increased activation in the middle temporal gyrus, the left inferior portion of the superior temporal gyrus and the left superior portion of the middle temporal gyrus. This suggests a multisensory response to the spoken language.

Figure 3 – Sung blocks contrasting religious versus non-religious stimuli. We can see increased activation in the posterior cingulate gyrus, suggesting a greater emotional response to religious song than to non-religious song