Sophie Determan, Roger Macfarlane, Comparative Arts & Letters

The goal of my project was to assist Dr. Roger Macfarlane in developing the online index of the Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in the Arts which will be centered at BYU. The OGCMA is an important and widely-used index that identifies 30,000+ artworks spanning from the 1300-1900s. But despite the breadth of the index, there is not a single example of a film mentioned in any entry. This is a serious gap in classical scholarship because no other guide contains significant film references. The scope of my project was to evaluate and contribute scholarly metadata for over forty films that will comprise the “Pygmalion” article in the OGCMA-online index.

Scrutinizing various well-known Pygmalion films and films proposed by others as Pygmalion films, one problem quickly became apparent – some ground rules needed to be established as to what constituted “the Pygmalion myth.” If the myth is merely about a beloved inanimate object coming to life, then even stories like The Velveteen Rabbit or Frosty the Snowman would have to be included. Likewise, if bones of the Pygmalion myth can be reduced to a George Bernard Shaw-esque transformation arc, then any and every makeover movie could be considered a “Pygmalion movie.”

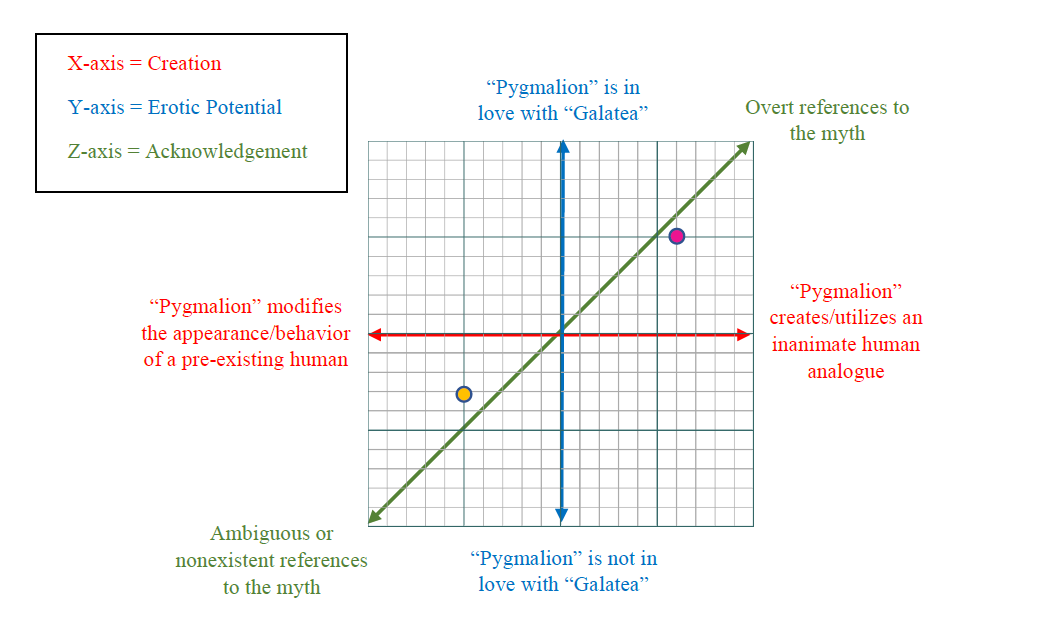

With these concerns in mind, we established criteria to judge whether a film is a deliberate adaptation of the myth or merely shares archetypal similarities. The most fundamental points of consideration were three: 1) whether Pygmalion’s activity in the narrative is an act of creation, 2) whether Pygmalion’s “Galatea” in the narrative bears erotic potential for the artist, and 3) whether the cinematic narrative acknowledges the Pygmalion myth overtly. This third category was particularly important to us considering Linda Hutcheon’s A Theory of Adaptation (2006) which defines “adaptations” as “deliberate, announced, and extended revisitations of prior works.” For a film to be included in the OGCMA, it needs to be a truly relevant example of the myth.

Dr. Macfarlane and I initially dubbed this set of criteria “the z-factor” and discussed films on a 1 through 5 scale with 1 being highly faithful to the myth and 5 bearing only a resemblance. The more films we analyzed, though, the more difficult it became to rank them against each other since treatments of the myth can vary so widely (consider the Pygmalion-inspired musicals My Fair Lady and The Rocky Horror Picture Show, for example). In order to make sense of our data, I began to plot the criteria on a simple grid system. This soon developed into a dynamic three-axis graph. This graph not only charts each film’s adaptive treatment of the myth, but also its relationship to fellow cinematic adaptations and the original foundation text.

One of the main advantages of this graph system is that it allows a film researcher or curious classics student to understand at a glance where a film lies in its narrative treatment of the Pygmalion myth. For instance, an adaptation like Miss Congeniality might have an (x,y,z,) graph value of (-5,-3,1) while Ruby Sparks might rank (6,5,-1).

This chart has become an effective tool as I assist Dr. Macfarlane in compiling films for inclusion in the Oxford Guide to Classical Mythology in the Arts. Not only can I explain which films I’ve analyzed, but also how each film uniquely interprets the foundation myth and where the film falls in the broader web of Pygmalion adaptations. This graph system also has value for the adaptation studies community in general since the three-axis format could be modified for comparisons of other popular works like Cinderella or Frankenstein.