Amanda Brower, Dr. Sheri Palmer, RN, DNP, CNE, CTN-A, BYU College of Nursing

Introduction

The refugee crisis has impacted nations and global health worldwide. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates there are currently 22.5 million refugees throughout the world (UN Refugee Agency, 2018). Since Fiscal Year 2016, over 300 refugees have resettled in the state of Utah (Refugee Processing Center, 2018); these individuals represent various cultures and health needs. Data from other regions of the world indicates there are great discrepancies and complications in maternal healthcare of refugees, including increasing risks of C-section births, preterm birth, low birth weight (LBW) infants, perinatal mortality, postpartum depression, and stillbirth (Lancaster 2017). Aim: The purpose of this study is to identify the most urgent maternal healthcare needs of pregnant refugee women in Utah.

Methodology

Study Design: An exploratory qualitative research method was used. Working closely with the International Rescue Committee (IRC) chapter in Salt Lake City, UT, we conducted the study at the Redwood Clinic. This clinic sees the largest percentage of refugees in the Salt Lake City area. Participants: Four pregnant female refugees, ages 18-40, receiving prenatal healthcare at the Redwood Clinic participated in this study. Three of their prenatal healthcare providers were also interviewed. The participants were recruited by word of mouth. Analysis: The interviews explored the nuances and complexities of being pregnant as a refugee in Utah. Verbal consent was obtained from the participants. Qualified interpreters were used. The research proposal was approved by the IRB offices of Brigham Young University (BYU) and the University of Utah (UofU).

Results

Five pregnant refugee women receiving healthcare at a local clinic, and their healthcare providers, were interviewed. Preliminary results indicate appropriate administration of culturally-sensitive healthcare, but indicate existing barriers to communication, transportation, and payment for services.

Discussion

Commendable, culturally-appropriate healthcare was observed. At monthly clinic-sponsored meetings, pregnant refugee clients gather with their healthcare providers for prenatal healthcare education in a culturally-sensitive group setting. Improved management of logistics (communication, transportation, financial) will occur through better implementation of interpretation services (widely available via iPad/mobile devices), acquisition of bus passes for refugee clients, and creation of simple, illustrated documents outlining healthcare procedures, medication instructions, and available financial resources.

Conclusion

Knowledge of the needs of pregnant refugee women is still in its infancy in Utah. Awareness and implementation of these interventions will decrease cultural, financial, transportation, and communication barriers faced by pregnant refugee clients.

Figure 1 – Example of illustrated, “refugee-friendly” document outlining instructions for patients undergoing a glucose tolerance test (a necessary test for pregnant women)

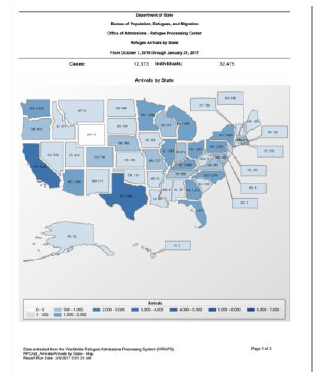

Figure 2 – Map showing refugee arrivals by state, Oct 2016—Jan 2017

References

Lancaster, E. (2017, February 19). Refugees and pregnancy. Retrieved from https://refugeewomenshealthaus.wordpress.com/2017/02/19/refugees-and-pregnancy/

Refugee Processing Center. (2018, March 31). Refugee admissions report. Retrieved from http://www.wrapsnet.org/admissions-and-arrivals/

UN Refugee Agency. (2018). Figures at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html