Delaney Barney and Faculty Mentor: Don Chapman, Department of Linguistics and English Language

Introduction

The popular view of usage manuals like Fowler’s Modern English Usage (1926) and Garner’s Modern American Usage (2003) is that they contain a well-established set of rules. We expect to find the same language rules we’ve been practicing since elementary school: say may I instead of can I when asking for permission, spell with “I” before “E,” and don’t split infinitives. Because most people only have one or two usage guides that they consult regularly, it’s easy to believe that they all have the same rules. I was interested in finding out how much variation there is from book to book. This research seeks to not only identify the differences between individual usage manuals, but to quantify those disparities as well.

Methodology

In order to identify and quantify the differences between English usage manuals, I started by categorizing the rules within them. I tabulated rules from 40 English usage manuals, published between 1891 and 2016. This tabulation includes the individual rules in each manual, a linguistic description of the rule, and a total tally of how many of the usage manuals list each rule. The linguistic description consisted of the broad category that the rule could be applied to (word meaning, word structure, sentence structure, spelling, and pronunciation, for example) as well as more specific categories (for example, whether it was a prefix or a suffix, or whether the rule dealt with noun forms or verb forms). I also kept track of the consequences for violating a rule, as given by the authors. The consequences were listed as “categorical” if there was a clear-cut right and wrong way to use language. Many of the rules did not have categorical consequences, but dealt with dialect, datedness, and currency of words and phrases. All of this information was stored in an excel spreadsheet, making it possible to sort and filter for different rule types while storing the consequence and tally data with each rule.

In one year of data collection, I compiled rules from the usage guide entries starting with D, E, F, and G (most of the books are arranged alphabetically, like a dictionary). This resulted in 14,326 individual rules. In my analysis, I look at the books individually and altogether.

Results

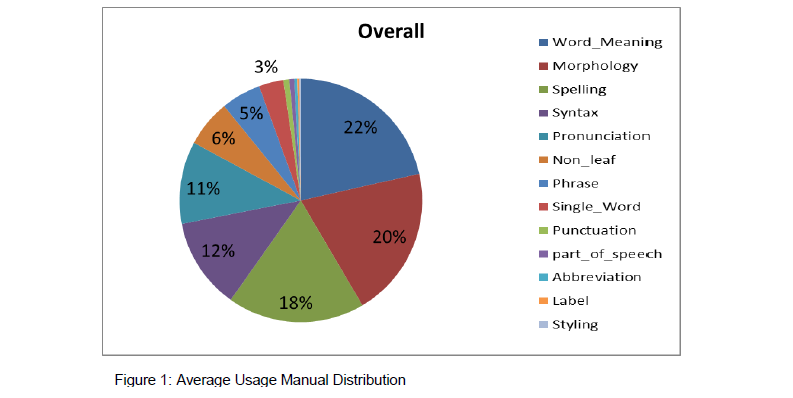

When we compare the average distribution of rules to each book’s profile, we see idiosyncratic distributions for most manuals. In order to measure these idiosyncrasies, I combined the distributions of the entire sample of rules to model an “average” usage manual (see figure 1). This was used as a baseline to compare the individual books to.

The most frequently mentioned rules from the sample are: fewer vs less (mentioned in 33 of the 40 manuals), data vs datum (32 manuals) different from vs different than (32), dangling modifiers (31), and farther vs further (31). These are the kinds of rules we expect from a monolithic set of English grammar rules. However, as we compare the distributions of rule types (the first level, broad linguistic categories that rules were sorted into) as well as the “one-offs,” rules that are only mentioned in one book, we see that each author places different amount of emphasis on each aspect of the language.

Using a distance-from-mean formula C=√((𝜇1−𝑉1)2+…+(𝜇𝑛−𝑉𝑛)2), we get a range of distance coefficients from C=7.96 (the most similar to the average) to C=37.79 (the least similar book to the average).

Discussion

While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly what makes certain books so average in their distributions, there are clear reasons for the idiosyncratic usage manuals. The least average, for example, addresses spelling in 45% of its rules, over twice as much as the average 18%. Another distinctive manual includes syntax rules in 42% of its entries, compared to the average 12%. This evidence shows that the authors are not objective when deciding which rules to include; they give more weight to certain parts of the language, and that weight varies from author to author. While these examples are extreme cases, the data show that every book has its own lean in some direction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we see that usage manuals are based on subjective decisions, not a standardized body of rules. It is inaccurate to assume that one usage manual has all of the rules, and it is equally inaccurate to assume that all the rules in one manual are equally recognized by other experts. A follow-up to this study could take the information coded into the consequences of not following the prescribed rules. This could show other biases that authors have regarding which language “mistakes” are okay and which are impermissible.