Heidi Pyper Faculty Mentor: Elliott D. Wise, Department of Comparative Arts and Letters

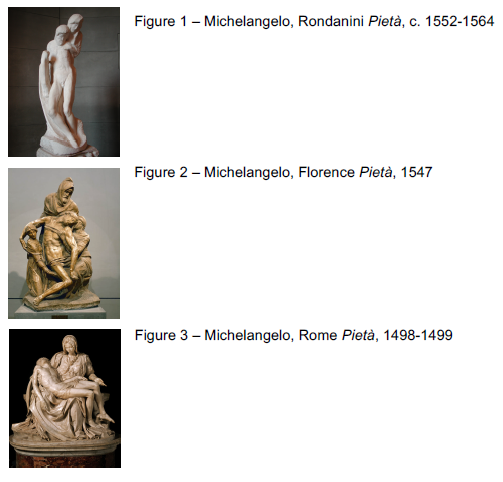

I organized this research project to better understand Michelangelo’s final work and

sculpture, the Rondanini Pietà, which contains an upright Jesus supported from behind

by Mary (Fig. 1). Michelangelo labored on the sculpture up until the last days of his life,

and it has even been suggested by John Paoletti that it was meant for the altar of his

burial chapel.1The Pietà subject depicts the apocryphal moment following the

Crucifixion, when Christ was removed from the cross and placed in Mary’s embrace.

Devotionally, the Pietà aids spiritual contemplation and prayer.

The most interesting aspect of the Rondanini Pietà is that it was sculpted, destroyed,

and reconstructed in distinct phases, yet many scholars simply regard the Pietà as an

unfinished portrayal of Mary and Christ. Some scholars have touched on the spiritual

nature of the sculpture, but with the belief that the artist rejected the earlier form for its

aesthetics or its failure to convey an emotional message. My research, however,

considers the full expression of the sculptural phases of the work as an intentional part

of the process—a process that facilitated active devotional meditation on the figures of

the sculptural group and on their functions.

In 2000, John Paoletti brought forth convincing evidence that the figure of Mary was

preceded by a Nicodemus figure in an earlier phase, but my research is the first to

expand on this insight and make a connection to the spiritually rich tradition of

meditation. It is widely believed that Michelangelo’s Florence Pietà (Fig. 2) contains a

self-portrait in the guise of Nicodemus, and Paoletti has also suggested a reappearance

of this portrait type in the early phase of the Rondanini Pietà. This makes the argument

for a meditative sculptural process much more personal and convincing. Michelangelo

could make himself physically present in the work and engage with the narrative of

Christ’s death and eventual rebirth from the tomb at various levels. He could enter the

scene as Nicodemus and eventually liken himself to the Virgin in the Passion narrative.

Another significant part of the sculptural process is that with the transformation from

Nicodemus to Mary, Christ’s figure was destroyed and re-created from the marble

“flesh” of the second figure. The sculptural process therefore reflects a meditation on

the Passion, but also on the “creation” of Christ— whose life was sacrificed by a loving

God, so that “whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.”

(John 3:16). Ultimately, Michelangelo could use the sculptural process as a form of

devotional meditation, so that through the figures of Nicodemus and Mary, he could

mystically participate in various levels of the Passion narrative and materially reproduce

the creation of Christ.

My research involved me personally travelling to Italy to see the Rondanini Pietà and

Michelangelo’s other Pietàs in Florence and in Rome. Though other scholars have

examined the Rondanini Pietà and documented the artist’s process, I was able to make

my own observations and assessments. I immersed myself in Michelangelo’s works,

the devotional history of the Pietà, and the spiritual tradition of meditation. I was able to

research Nicodemus and Mary as subjects of spiritual contemplation and as archetypal

Christian creators, with whom Michelangelo could identify. Nicodemus and Mary are

prominent figures in the Bible and in meditational texts. It is believed that Mary was

present at the Crucifixion and received Christ unto herself following the

Deposition. She also facilitated the Incarnation of God as he was made flesh in her

womb. Nicodemus likewise played a role at the Crucifixion in removing the nails from

his body and placing his body in the sepulcher with Joseph of Arimathea. Nicodemus

was also the believed sculptor of the wooden crucifix, the Volto Santo, and the patron

saint of sculptors. Through my research, I discovered an early devotional significance

and connection to Nicodemus and Mary in both the Florence Pietà and Rome Pietà

(Fig. 3). I also found other examples of artists identifying with Nicodemus and Mary.

My methodology is rooted in the theory of materiality, taking into account the threedimensional

nature of marble and its likeness to flesh and the medium of the

imagination. Ultimately, my research culminated in my honors thesis and will be

submitted to the Bowdoin Journal of Art for publication.

1 John T. Paoletti, “The Rondanini “Pieta”: Ambiguity Maintained through the Palimpsest,” Artibus et Historiae 21, no.

42 (2000): 53-80.