Kirsten Watkins and Mary Farahnakian, Department of Theatre and Media Arts

With the end of World War II came a drastic change in fashion. Gone were the stiff shoulders and narrow silhouettes and in came the New Look of 1947, designed by Christian Dior. This look emphasized soft curves, narrow waists, and large wide skirts—a far cry from wartime fashions where fabric was rationed and such skirts were seen as a luxury that few could afford. With this change of fashion came a change in hats. While wartime hats were still widely worn, many new hats came onto the scene. This decade became the culmination of different hat styles from the large to the small, the formal to the casual, and the simple to the extravagant. They were a necessity, for a woman wouldn’t be seen out of the house without her hat and gloves. More than that, the hat became the exclamation point to a woman’s ensemble, each with a unique style.

My project for the Office of Research and Creative Activities was creating a display in the Harold B. Lee Library using hats that are from BYU’s Historic Clothing Collection which boasts over 4,000 articles of clothing and accessories from early 1800s to present day. In this collection there are about 700 hats, with around 250 of those hats from the 1950s from which I selected 21 iconic hats to put on display. My research began with a general overview of fashion history in the twentieth century, contextualizing the fashion history of the 1950s. This decade is notable because it was a departure from previous decades’ fashion and was “marked by a strong sense of recovery and hope for a democratic and prosperous future where war would never come again.”1 People and fashion were optimistic and new ideas for designs were abundant and often very romantic in an attempt to bring back old-fashioned femininity. Everything was circular and soft – made with felts and feathers, beads and straw, and usually swathed with yards of veiling.

One of my jobs at BYU has been to work on the rehousing of BYU’s Historic Clothing Collection under the direction of the Harold B. Lee Library and the Museum of Peoples and Cultures. As part of this job, I moved the Collection from the warehouse where they were stored to the library so they can become accessible for future research. In the process of moving the artifacts, I carefully replaced the box where they were stored as well as the tissue in the clothing and completed a condition report for each article. I checked for rot, bugs, staining, silk shattering, etc. The hats were no different. I sorted through the 250 hats from the decade, making notes along the way of condition, styles, colors, and materials. Each hat was photographed and rehoused, padded out with tissue paper to help preserve the shape and integrity of each piece. My notes about the hats that BYU owns as well as the research that I was conducting about the decade coincided to help me select the 21 hats that I chose to exhibit.

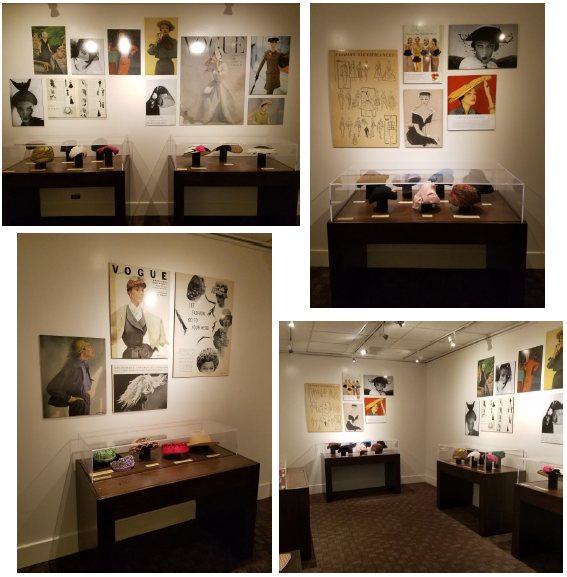

The Museum of Peoples and Cultures generously lent me four display cases to use in my exhibit and I divided the hats into four sections: summer hats, winter hats, formal hats, and large hats. I selected iconic hats that fit within those categories and carefully made mounts to fit each of the hats in order to display them. I used fosshape, a nonwoven fabric that can be molded into certain shapes with the use of heat, to create the base for the hats to sit on and cardboard tubes covered in velvet to support them. I also started going through primary sources, such as Vogue and Butterwick (popular magazines at the time), for images to print and mount on the wall to show an even wider variety of hats. Some of the popular styles that I included, either in artifact or picture form were: beret, boater, bonnet, bowler, cloche, cocktail (aka bibi), fedora, lampshade, mushroom cloche, Panama, pillbox, and skull cap. I also included two hats in the exhibit from two famous designers: Christian Dior and Elsa Schiaparelli.

All this work resulted in a month long exhibit in the Gallery on Five in the HBLL. There were 21 hats, 17 pictures from primary sources, and 1 hat pattern from a 1951 Vogue Pattern Book for people to take and make if they chose.

It was surprisingly challenging to create a museum exhibit. I wanted to create something nostalgic but was still relevant to people today. Why should people of 2016 care about hats from the 1950s? Why is it important to study these things? Clothing tells stories. It tells stories about the zeitgeist of the times: about economics, politics, and religion, about world issues and cultural influence. But more importantly, it tells stories about people, about their cares and dreams. It tells stories of family and community. I left a comment book so that people could leave their thoughts and impressions about the exhibit and several people mentioned the fact that it brought back memories of their mothers, grandmothers, and other important women in their lives. It is important to remember these stories. While I did not live in the 1950s, I am inspired by the stories of optimism and innovation after such a devastating war and throughout the Cold War. Regardless of the terrors that happen in the world, studying these hats and the stories that surround them taught me that we can always create beautiful things. It is something that is inherent within us. President Dieter F. Uchtdorf said, “The desire to create is one of the deepest yearnings of the human soul.”2 The very act of creating is an act of strength. It allows us in 2016 to see those who lived in the 1950s in a completely new light. Their lives are not just a couple of paragraphs in a history book full of politics and world events but a community of people who lived, loved, and created.

In the 1960s, hats started to die off. Hairstyles and economics changed. Celebrities no longer wore hats and the public followed suit. Hats never regained the popularity that they once enjoyed—the 1950s were indeed the final heyday for hats. Even though we no longer wear hats as a part of our daily ensemble, studying the fashions of the past is important to learn about the lives of the people who lived through it. I am grateful for the opportunity that I had to study these hats and to learn more about museum conservation and curation. Clothing history has always been fascinating to me and I hope to be able to build off the scholarship and skills that I learned from this project in the future. Thank you.

1 Hopkins, Susie. “The Golden Years.” The Century of Hats: Headturning Style of the Twentieth Century. Edison, NJ: Chartwell, 1999. 82. Print.

2 Uchtdorf, Dieter F. “Happiness, Your Heritage.” The Church of Jesus Christ of Later-Day Saints, Oct. 2008. Web. 30 Aug. 2016. <https://www.lds.org/general-conference/2008/10/happiness-your-heritage?lang=eng&_r=1>.

Selected Bibliography

- Clark, Fiona. Hats. London: B.T. Batsford, 1982. Print. Courtais, Georgine De. “Twentieth Century.” Women’s Headdress and Hairstyles: In England from AD 600 to the Present Day. London: Batsford, 1986. 160-67. Print.

- Farrell-Beck, Jane, and Jean Louise Parsons. “1947-1958: New Wealth, New Looks.” Twentieth-Century Dress in the United States. New York: Fairchild Publications, 2007. 132-57. Print.

- Hopkins, Susie. “The Golden Years.” The Century of Hats: Headturning Style of the Twentieth Century. Edison, NJ: Chartwell, 1999. 82-95. Print.

- Mendes, Valerie D., Amy De La Haye, and Valerie D. Mendes. Fashion Since 1900. London: Thames and Hudson, 2010. Print.