Trenton Hyer and Faculty Mentor: Dirk Elzinga, Department of Linguistics

Introduction

The objective of this project is to document word borrowing in Riograndenser Hunsrückisch, an understudied variety of German spoken in southern Brazil. UNESCO’s The Red Book of Endangered Languages listed Riograndenser Hunsrückisch as an endangered language in 1992, but linguists have written very little about it since.

Riograndenser Hunsrückisch has been the heritage language of German immigrants living in the southernmost states of Brazil since immigration began in the 18th century and is now endangered. Because of the region’s cultural remoteness and general antipathy between Portuguese and German speaking Brazilians, few linguists have researched or written about Hunsrückisch.

Given the long-time isolation of the language group, one important question is how do these speakers come up with new words? As new ideas and technologies emerge, what languages influence the borrowing patterns of Hunsrückisch? Documenting the process of word borrowing would be a contribution to language, history, and culture.

Methodology

The discovery process took place in three main stages: creating a list of candidate words, eliciting responses from native speakers, and analyzing the responses according to known data about each word.

Creating a list of candidate words required finding lexical items that fit a very specific set of criteria. These words needed to:

- Be common-knowledge words the average speaker would know

- First come into use during the period of interest (1890-present)

- Have different forms in Portuguese and German (phonetic, in some cases)

Words were cross-validated by comparing with frequency information and historical data available through the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA) and Corpus do Português (CdP). After taking all candidate words through these checks, a final list of 100 items was created and used for elicitation. Elicitation took place by way of interviews, with the participant being asked to give a translation for the items. Occasionally, hand drawings or images were used to avoid priming participants toward a known Portuguese cognate. In total, this study consisted of 10 interviews and 11 participants.

Results

As is common in work with understudied language variants, the expected results of these interviews varied drastically with the actual data collected. At onset of the project, the anticipated purpose was to describe the way that native speakers of Riograndenser Hunsrückisch create new words. Instead, this elicited word set shows that the use of Hunsrückisch is contracting its use to certain spheres (in the home and local community) within the south of Brazil, and in most of the lexical categories these items came from, speakers had no non-Portuguese vocabulary to provide translations or otherwise describe the words and phrases elicited.

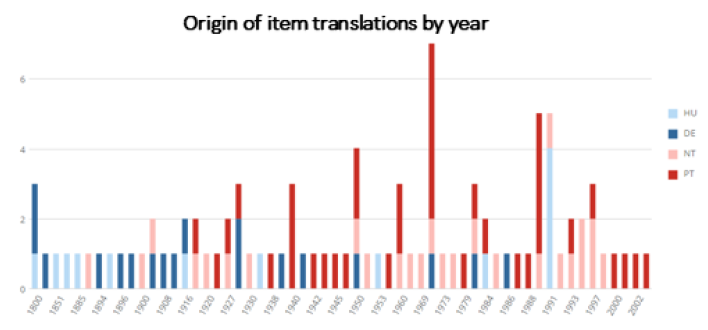

The following chart shows the trend of word creation over time – each bar represents total items that year from each respective origin. Light blue represents newly synthesized words (uniquely different from Portuguese and German), dark red represents Portuguese origins/equivalency, and dark blue represents German origins. Light red indicates words for which respondents did not know the translation or did not believe a translation existed.

Discussion

The color scheme chosen above was intentional – light and dark blue represent Germanic origins while the reds indicate Portuguese or no translation. Note that while the blues dominate the early years, there seems to be a turning point in the first half of the twentieth century. This coincides with historical patterns – during World War II, speaking German was forbidden in southern Brazil. New words of German origin and invented Hunsrückisch words only occur thereafter with great infrequency (excepting 1991, in which three of the four terms are all morphologically well-suited to a Hunsrückisch adaptation).

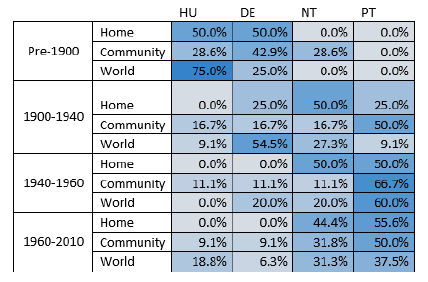

Percent of each category’s item origins by year. From top to bottom, the general language trend is shifting away from German/Hunsrückisch and toward Portuguese. Note that very few new home or community items occurred in the last 50 years.

On the other hand, the influence of Portuguese has come to totally dominate most spheres of language use, all the way from home electronics to big world trends and ideas. When speakers need to express a new word, they generally use Portuguese.

Note that NT (no translation) and PT (Portuguese) delegations since 1940 are often equivalent with each other depending on how the participant preferred to categorize the translation. Some insisted that the Portuguese term was used within Hunsrückisch sentences while others claimed there was no way to use the item in Hunsrückisch without switching to Portuguese. Either way the speaker preferred to define it, these terms appear to be clearly treated as Portuguese and not borrowed terms that are now part of Hunsrückisch.

Conclusion

Riograndenser Hunsrückisch is contracting in its realm of influence. Where it once dominated the community of native speakers, it is now mostly a language variant used at home, socially, and in some specific work situations. Its life expectancy as a language of influence appears to be short unless the native speakers are able to expand its use to include emerging technologies and ideas.