Alejandra Gimenez and J. Quin Monson, Political Science

Studies on political recruitment have increased over the past few years, and specifically that of female recruitment in regards to political candidacy. Studies have shown strong evidence that recruitment increases participation, both in activism and candidacy. However, much of this work focuses on the effects of recruitment among a pool of subjects who are already more likely to run than the average citizen. What is unclear is whether recruitment deepens the pool of potential candidates or simply triggers those who are already in the pool to run. In this paper, I argue that political recruitment does not increase the number of newly-interested candidates but rather motivates existing candidates to run for higher leadership offices.

To investigate the effects of political recruitment, a statewide field experiment was conducted in cooperation with the state’s Republican Party through their caucusconvention system. As a treatment, all precinct chairs received a letter with differing instructions immediately before the caucus meetings. Precinct chairs were assigned to the control condition or one of three treatments in which they were asked to either personally recruit two to three women to run, to read a paragraph on caucus night from the state party chair asking caucus attendees to elect more women as state delegates, or to do both. Using these data, Karpowitz, Monson, and Preece (2015) find that the combined treatment significantly increased the proportion of female state delegates. Karpowitz, Monson, and Preece (2015) present the findings from the main experiment in a separate paper. This paper focuses on the mechanism underlying those findings.

But did this combined treatment bring new women into party politics or simply shift women from other party offices? In order to investigate the effects of the treatments on the number of women running, trained observers were sent to a subset of treated precincts to gather data on the proceedings and the candidates. In order to understand the mechanisms of the treatments on the caucus meeting dynamics including who ran, data beyond what the party could provide for Karpowitz, Monson, and Preece needed to be collected (2015). As such, 257 trained student observers were sent to 150 caucus meetings to gather data on the meeting happenings. The observed precincts were randomly selected across all four conditions within a two-hour radius of the students’ universities. While that area may seem small, it covers approximately 80% of the population of the state, therefore providing good coverage. Prior to attending the caucuses, students were trained and given a guided notes sheets on which they were ask to record the following items:

- Whether or not the precinct official followed party protocol and rules

- Candidate name and gender for each office nomination period (including the names and genders of individuals who were nominated but did not accept)

- Candidate speeches and Q&A content for each office nomination period

- Overall notes for each office nomination period

- Overall impressions of the whole meeting

To ensure that the observers were blind to the experiment, they were told that this was a study on caucus proceedings generally. Keeping the students blind also ensured that they wouldn’t divulge the experiment to any precinct officials or attendees should they be asked what they were doing.

After they attended the caucus meetings, students entered their notes into a Qualtrics form that mirrored their guided notes sheet. The students were asked to write whatever they heard during the meeting and then to transcribe exactly what they wrote during the meeting. They were given 24 hours to enter the data, with most of the students entering their data the night of the caucus meeting. After the students entered the data, they returned the physical copy of their notes should anything happen to the digital version. All data was verified for accuracy.

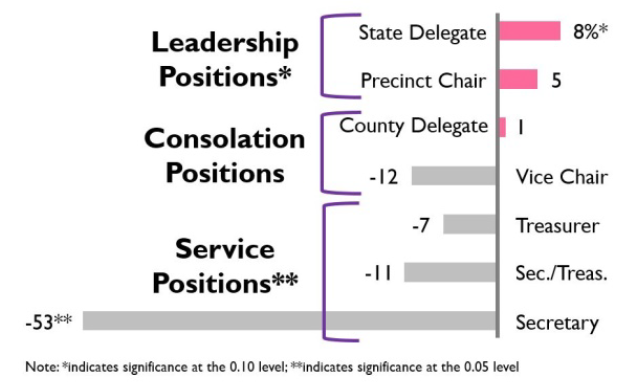

Similar to the statewide election returns, the combined treatment increased the number of female state delegate candidates. In the combined supply and demand condition, there is a significant increase in the number women running for state delegate and a significant decrease in the number of women running for secretary. The gender balance among state delegates increased by 8 percentage points, increasing the percentage of female candidates to 33 percent. Most interesting, perhaps, is the large decrease of female running for secretarial positions. In the control, 80% of secretarial candidates were females. In the supply and demand treatment, only 27% of secretarial candidates were female, a drastic decrease of 53 percentage points. These same patterns follow in the individual Supply and Demand conditions, though no significant changes occur. However, the overall number of candidates did not significantly change, suggesting that these treatments initiated a shift among already existing candidates. The treatments encouraged women to run for leadership-type positions and men to run for the service positions the women typically held. This research has important implications for the effects of recruitment among audiences with varying political activity.

Figure 1- The number of female candidates for state delegate increases and the number of female candidates decreases. Candidates group into three categories: leadership positions, consolation positions, and service positions. More women are running for leadership positions and fewer women are running for service positions. As discussed earlier, leadership positions tend to be male dominated. Women also have higher qualification expectations for themselves attached to these leadership positions. On the other hand, service positions tend to be female dominated. These same patterns of gendered leadership and service positions are most definitely present in the control condition in regards to gendered leadership and service positions. However, the treatment for the Supply+Demand condition encourages significantly more women to not only run for a different position but to run for a leadership position. In response, more men are running for the service positions to fill the gap left by the women.